Soviet invasion of Poland

Subsequent military operations lasted for the following 20 days and ended on 6 October 1939 with the two-way division and annexation of the entire territory of the Second Polish Republic by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

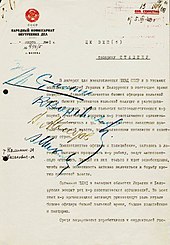

Some 13.5 million Polish citizens who fell under the military occupation were made Soviet subjects following show elections conducted by the NKVD secret police in an atmosphere of terror,[12][13][14] the results of which were used to legitimise the use of force.

A Soviet campaign of political murders and other forms of repression, targeting Polish figures of authority such as military officers, police, and priests, began with a wave of arrests and summary executions.

This agreement recognized the status quo as the new official border between the two countries, with the exception of the region around Białystok and a minor part of Galicia east of the San River around Przemyśl, which were later returned to Poland.

[20] In early 1939, several months before the invasion, the Soviet Union began strategic alliance negotiations with the United Kingdom and France against the crash militarization of Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler.

[22][Note 7] At the opening of hostilities several Polish cities including Dubno, Łuck and Włodzimierz Wołyński let the Red Army in peacefully, convinced that it was marching on in order to fight the Germans.

[31] Józef Piłsudski sought to expand the Polish borders as far east as possible in an attempt to create a Polish-led federation, capable of countering future imperialist action on the part of Russia or Germany.

After all foreign interventions had been repelled, the Red Army, commanded by Trotsky and Stalin (among others) started to advance westward towards the disputed territories intending to encourage Communist movements in Western Europe.

In mid-April, the Soviet Union, Britain and France began trading diplomatic suggestions regarding a political and military agreement to counter potential further German aggression.

[44] The Soviets did not trust the British or the French to honour a collective security agreement, because they had refused to react against the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War and let the occupation of Czechoslovakia happen without effective opposition.

[45] Robert C. Grogin (author of Natural Enemies) contends that Stalin, had been "putting out feelers to the Nazis" through his personal emissaries as early as 1936 and desired a mutual understanding with Hitler as a diplomatic solution.

[46] The Soviet leader sought nothing short of an ironclad guarantee against losing his sphere of influence,[47] and aspired to create a north–south buffer zone from Finland to Romania, conveniently established in the event of an attack.

[56] By late July and early August 1939, Soviet and German diplomats had reached a near-complete consensus on the details for a planned economic agreement and addressed the potential for a desirable political accord.

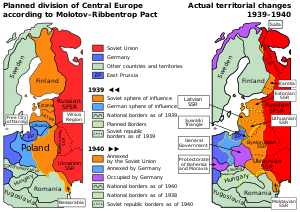

This pact included terms of mutual non-aggression and contained secret protocols, that regulated detailed plans for the division of the states of northern and eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

[66] At midnight of 29 August, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop handed British Ambassador Nevile Henderson a list of terms that would allegedly ensure peace with regard to Poland.

[70][71] On the following day (1 September) Hitler announced, that official military actions against Poland had commenced at 4:45 a.m.[68] German air forces bombarded the cities Lwow and Łuck.

[73] Foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop commissioned the German Embassy in Moscow with the assessment of and the report on the likelihood of Soviet intentions for a Red Army invasion into Poland.

Molotov and ambassador von der Schulenburg discussed the matter repeatedly but the Soviet Union nevertheless delayed the invasion of eastern Poland, while being occupied with events unfolding in the Far East in relation to the ongoing border disputes with Japan.

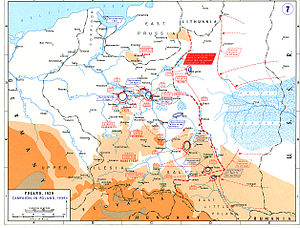

Due to determined Polish defense and a lack of fuel, the German advance had stalled and the situation stabilized in the areas east of the line Augustów – Grodno – Białystok – Kobryń – Kowel – Żółkiew – Lwów – Żydaczów – Stryj – Turka.

According to historian and author Leszek Moczulski, approximately 750,000 soldiers remained active in the Polish Army, whereas Czesław Grzelak and Henryk Stańczyk arrived at an estimated strength of 650,000 troops.

Due to the ongoing battles in the area around Warsaw, Modlin, the Bzura, at Zamość, Lwów and Tomaszów Lubelski, most German divisions had been ordered to fall back towards these locations.

[90] As a result, Polish commanders focused on massive troop deployment designs and elaborate operational exercises in the west in order to successfully counter all German invasion attempts.

[1][91] During the Red Army invasion on 17 September, most Polish units had engaged in a fighting retreat towards the Romanian Bridgehead, where, according to overall strategic plans all divisions were to regroup and await new orders in coordination with allied British and French forces.

[citation needed] Commander-in-chief Edward Rydz-Śmigły was initially inclined to order the eastern border forces to oppose the invasion, but was dissuaded by Prime Minister Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski and President Ignacy Mościcki.

Notable occurrences of co-operation in the field among the two armies were reported, for example, as Wehrmacht troops passed the Brest Fortress, which had been seized after the Battle of Brześć Litewski to the Soviet 29th Tank Brigade on 17 September.

[100] Local Communists gathered people to welcome the Red Army troops in the traditional Slavic way by presenting bread and salt in the eastern suburb of Brest.

[106] When Polish Ambassador Edward Raczyński reminded Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax of the pact, he was bluntly told that it was Britain's exclusive right to declare war on the Soviet Union or not.

[103] This stance represented Britain's attempt at balance as its security interests included trade with the USSR that would support its war effort and might lead to a possible future Anglo-Soviet alliance against Germany (which indeed happened two years later).

[2] By this arrangement, often described as a fourth partition of Poland,[1] the Soviet Union secured almost all Polish territory east of the line of the rivers Pisa, Narew, Western Bug and San.

[92] The border created in this agreement roughly corresponded to the Curzon Line drawn by the British in 1919, a point that would successfully be utilized by Stalin during negotiations with the Allies at the Teheran and Yalta Conferences.