Political repression in the Soviet Union

[9] Liebman noted that opposition parties such as the Cadets who were democratically elected to the Soviets in some areas, then proceeded to use their mandate to welcome in Tsarist and foreign capitalist military forces.

[9] In one incident in Baku, the British military, once invited in, proceeded to execute members of the Bolshevik Party who had peacefully stood down from the Soviet when they failed to win the elections.

[9] Trotsky also argued that he and Lenin had intended to lift the ban on the opposition parties such as the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries as soon as the economic and social conditions of Soviet Russia had improved.

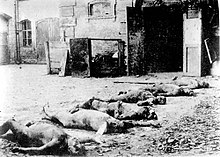

During the Tambov rebellion, Mikhail Tukhachevsky (chief Red Army commander in the area) authorized Bolshevik military forces to use chemical weapons against villages with civilian population and rebels.

[13] The Internal Troops of the Cheka and the Red Army practiced the terror tactics of taking and executing numerous hostages, often in connection with desertions of forcefully mobilized peasants.

[16] According to Figes, "a majority of deserters (most registered as "weak-willed") were handed back to the military authorities, and formed into units for transfer to one of the rear armies or directly to the front".

[25] However, social scientist Nikolay Zayats from the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus has argued that the figures have been greatly exaggerated due to White Army propaganda.

[29] In 1924, anti-Bolshevik Popular Socialist Sergei Melgunov (1879–1956) published a detailed account on the Red Terror in Russia, where he cited Professor Charles Saroléa's estimates of 1,766,188 deaths from the Bolshevik policies.

[35] Collectivization in the Soviet Union was a policy, pursued between 1928 and 1933, to consolidate individual land and labour into collective farms (Russian: колхо́з, kolkhoz, plural kolkhozy).

Collectivization was thus regarded as the solution to the crisis in agricultural distribution (mainly in grain deliveries) that had developed since 1927 and was becoming more acute as the Soviet Union pressed ahead with its ambitious industrialization program.

In his conversation with Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin gave his estimate of the number of "kulaks" who were repressed for resisting Soviet collectivization as 10 million, including those forcibly deported.

[42][43][44][45][46] On September 15, 1933, the deputy head of the OGPU, Genrikh Yagoda reported to Joseph Stalin about the disclosure of the "conspiracy of the homosexual community" in Moscow, Leningrad and Kharkiv.

As Yagoda pointed out in the explanatory note, "the conspirators were engaged in the creation of a network of salons and other organized formations, with the subsequent transformation of these associations into direct spy cells".

At the first stage, about 130 people were arrested who gave the necessary confessions under torture, and on December 17, 1933, the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR decided to extend criminal liability to "unnatural relationship".

"[58][59] During the early years of World War II, the Soviet Union annexed several territories in Eastern Europe as a consequence of the German–Soviet Pact and its Secret Additional Protocol.

Some scholars assert that record-keeping of the executions of political prisoners and ethnic minorities are neither reliable nor complete;[65] others contend archival materials contain irrefutable data far superior to sources utilized prior to 1991, such as statements from emigres and other informants.

[28] Rudolph Rummel in 2006 said that the earlier higher victim total estimates are correct, although he includes those killed by the government of the Soviet Union in other Eastern European countries as well.

[72] Conversely, J. Arch Getty and Stephen G. Wheatcroft insist that the opening of the Soviet archives has vindicated the lower estimates put forth by "revisionist" scholars.

"[75] Australian historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft claims that prior to the opening of the archives for historical research, "our understanding of the scale and the nature of Soviet repression has been extremely poor" and that some specialists who wish to maintain earlier high estimates of the Stalinist death toll are "finding it difficult to adapt to the new circumstances when the archives are open and when there are plenty of irrefutable data" and instead "hang on to their old Sovietological methods with round-about calculations based on odd statements from emigres and other informants who are supposed to have superior knowledge.

[67] A Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Political Repression (День памяти жертв политических репрессий) has been officially held on 30 October in Russia since 1991.

[95] The Wall of Grief in Moscow, inaugurated in October 2017, is Russia's first monument ordered by presidential decree for people killed during the Stalinist repressions in the Soviet Union.