Space Shuttle design process

All of this was taking place in the midst of other NASA teams proposing a wide variety of post-Apollo missions, a number of which would cost as much as Apollo or more.

This became especially pressing as it became clear that the Saturn V would no longer be produced, which meant that the payload to orbit needed to be increased in both mass - all the way to 60,600 pounds (27,500 kg) - and size to supplement its heavy-lift capabilities, necessary for planned interplanetary probes and space station modules, which meant a bigger and costlier vehicle was needed during Phase B.

The combined space station and Air Force payload requirements were not sufficient to reach desired shuttle launch rates.

The reusable booster was eventually abandoned due to several factors: high price (combined with limited funding), technical complexity, and development risk.

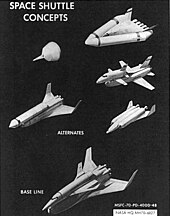

Instead, a partially (not fully) reusable design was selected, where an external propellant tank was discarded for each launch, and the booster rockets and shuttle orbiter were refurbished for reuse.

However, studies showed carrying the propellant in an external tank allowed a larger payload bay in an otherwise much smaller craft.

However NASA ultimately chose a gliding orbiter, based partially on experience from previous rocket-then-glide vehicles such as the X-15 and lifting bodies.

NASA examined four solutions to this problem: development of the existing Saturn lower stage, simple pressure-fed liquid-fuel engines of a new design, a large single solid rocket, or two (or more) smaller ones.

Engineers at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (where the Saturn V development was managed) were particularly concerned about solid rocket reliability for crewed missions.

During the mid-1960s the United States Air Force had both of its major piloted space projects, X-20 Dyna-Soar and Manned Orbiting Laboratory, canceled.

The Air Force launched more than 200 satellite reconnaissance missions between 1959 and 1970, and the military's large volume of payloads would be valuable in making the shuttle more economical.

[3]: 213–216 In turn, by serving Air Force needs, the Shuttle became a truly national system, carrying all military as well as civilian payloads.

In addition, the straight-wing configuration favored by Max Faget would've required the vehicle to fly in a stall for most of the reentry and had issues during launch aborts, a situation disliked by NASA.

Despite the potential benefits for the Air Force, the military was satisfied with its expendable boosters, and had less need for the shuttle than NASA.

Because the space agency needed outside support, the Defense Department (DoD) and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) gained primary control over the design process.

In exchange for the NASA concessions, the Air Force testified to the Senate Space Committee on the shuttle's behalf in March 1971.

[8] Potential military use of the shuttle—including the possibility of using it to verify Soviet compliance with the SALT II treaty—probably caused President Jimmy Carter to not cancel the shuttle in 1979 and 1980, when the program was years behind schedule and hundreds of millions of dollars over budget.

In the spring of 1972 Lockheed Aircraft, McDonnell Douglas, Grumman, and North American Rockwell submitted proposals to build the shuttle.

The NASA selection group thought that Lockheed's shuttle was too complex and too expensive, and the company had no experience with building crewed spacecraft.