Space Launch System

The rocket has been criticized for its political motivations, seen as a way to preserve jobs and contracts for aerospace companies involved in the Shuttle program at great expense to NASA.

[23][24] It is made mostly of 2219 aluminum alloy,[25] and contains numerous improvements to manufacturing processes, including friction stir welding for the barrel sections, and integrated milling for the stringers.

They possess an additional center segment, new avionics, and lighter insulation, but lack a parachute recovery system, as they will not be recovered after launch.

The ICPS is intended as a temporary solution and slated to be replaced on the Block 1B version of the SLS by the next-generation Exploration Upper Stage, under design by Boeing.

[44][45][46] Block 1 is intended to be capable of lifting 209,000 lb (95 t) to low Earth orbit (LEO) in this configuration, including the weight of the ICPS as part of the payload.

[47] At the time of SLS core stage separation, Artemis I was travelling on an initial 1,806 by 30 km (1,122 by 19 mi) transatmospheric orbital trajectory.

[55] As of March 2022[update], Boeing is developing a new composite-based fuel tank for the EUS that would increase Block 1B's overall payload mass capacity to TLI by 40 percent.

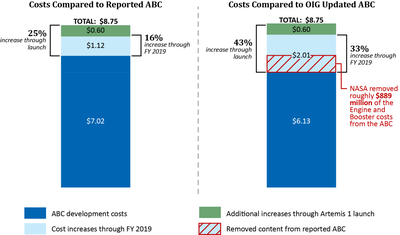

[70] In August 2014, as the SLS program passed its Key Decision Point C review and was deemed ready to enter full development, costs from February 2014 until its planned launch in September 2018 were estimated at $7.021 billion.

[72] In October 2018, NASA's Inspector General reported that the Boeing core stage contract had made up 40% of the $11.9 billion spent on the SLS as of August 2018.

[92] In January 2024 NASA announced plans for a first crewed flight of the Orion spacecraft on the SLS, the Artemis II mission, no earlier than September 2025.

[110][111][112][113] The SLS has considered several future development routes of potential launch configurations, with the planned evolution of the blocks of the rocket having been modified many times.

[100][120] The overly powerful advanced booster would have resulted in unsuitably high acceleration, and would need modifications to Launch Complex 39B, its flame trench, and Mobile Launcher.

[122] On 7 August 2014, the SLS Block 1 passed a milestone known as Key Decision Point C and entered full-scale development, with an estimated launch date of November 2018.

[126] In 2018, Blue Origin submitted a proposal to replace the EUS with a cheaper alternative to be designed and fabricated by the company, but it was rejected by NASA in November 2019 on multiple grounds; these included lower performance compared to the existing EUS design, incompatibility of the proposal with the height of the door of the Vehicle Assembly Building being only 390 feet (120 m), and unacceptable acceleration of Orion components such as its solar panels due to the higher thrust of the engines being used for the fuel tank.

A November 2021 report estimated that, at least for the first four launches of Artemis program, the per-launch production and operating costs would be $2.2 billion for SLS, plus $568 million for Exploration Ground Systems.

[32] The core stage for the first SLS, built at Michoud Assembly Facility by Boeing,[144] had all four engines attached in November 2019,[145] and it was declared finished by NASA in December 2019.

[147] The static firing test program at Stennis Space Center, known as the Green Run, operated all the core stage systems simultaneously for the first time.

[151] The second fire test was completed on 18 March 2021, with all four engines igniting, throttling down as expected to simulate in-flight conditions, and gimballing profiles.

[157][156] The Artemis II forward skirt, the foremost component of the core stage, was affixed on the liquid oxygen tank in late May 2021.

[202] It was postponed to 2:17 pm EDT (18:17 UTC), 3 September 2022, after the launch director called a scrub due to a temperature sensor falsely indicating that an RS-25 engine's hydrogen bleed intake was too warm.

[230] As of October 2024,[update] NASA has studied using SLS for Neptune Odyssey,[232][233] Europa Lander,[234][235][236] Enceladus Orbilander, Persephone,[237] HabEx,[238] Origins Space Telescope,[239] LUVOIR,[240] Lynx,[241] and Interstellar probe.

Reuters reported that the US Department of Defense, long considered a potential customer, stated in 2023 that it has no interest in the rocket as other launch vehicles already offer them the capability that they need at an affordable price.

[139] The SLS has been criticized based on program cost, lack of commercial involvement, and non-competitiveness of legislation requiring the use of Space Shuttle components "where possible".

[244] As the Space Shuttle program drew to a close in 2009, the Obama administration convened the Augustine Commission to assess NASA's future human spaceflight endeavors.

The administration further advocated for a public-private partnership, where private companies would develop and operate spacecraft, and NASA would purchase launch services on a fixed-cost basis.

The program was characterized by a complex web of political compromises, ensuring that various regions and interests benefited, maintaining jobs and contracts for existing space shuttle contractors.

Florida Senator Bill Nelson brought home billions of dollars to Kennedy Space Center to modernize its launch facilities.

The White House sent Lori Garver, the NASA deputy administrator, along with astronaut Sally Ride and other experts to defend the proposal, saying the SLS program was too slow and wasteful.

[246] In 2023, Cristina Chaplain, former assistant director of the GAO, expressed doubts about reducing the rocket's cost to a competitive threshold, "just given the history and how challenging it is to build.

"[139] In 2019, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted that NASA had assessed the performance of contractor Boeing positively, though the project had experienced cost growth and delay.