Spacecraft flight dynamics

It cannot be reduced to simply attitude control; real spacecraft do not have steering wheels or tillers like airplanes or ships.

Unlike the way fictional spaceships are portrayed, a spacecraft actually does not bank to turn in outer space, where its flight path depends strictly on the gravitational forces acting on it and the propulsive maneuvers applied.

where, The effective exhaust velocity of the rocket propellant is proportional to the vacuum specific impulse and affected by the atmospheric pressure:[4]

where: The specific impulse relates the delta-v capacity to the quantity of propellant consumed according to the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation:[5]

where: Aerodynamic forces, present near a body with a significant atmosphere such as Earth, Mars or Venus, are analyzed as: lift, defined as the force component perpendicular to the direction of flight (not necessarily upward to balance gravity, as for an airplane); and drag, the component parallel to, and in the opposite direction of flight.

Lift and drag are modeled as the products of a coefficient times dynamic pressure acting on a reference area:[6]

In-flight calculations will take perturbation factors into account such as the Earth's oblateness and non-uniform mass distribution; and gravitational forces of all nearby bodies, including the Moon, Sun, and other planets.

Preliminary estimates can make some simplifying assumptions: a spherical, uniform planet; the vehicle can be represented as a point mass; solution of the flight path presents a two-body problem; and the local flight path lies in a single plane) with reasonably small loss of accuracy.

[7] The general case of a launch from Earth must take engine thrust, aerodynamic forces, and gravity into account.

where: Mass decreases as propellant is consumed and rocket stages, engines or tanks are shed (if applicable).

For most launch vehicles, relatively small levels of lift are generated, and a gravity turn is employed, depending mostly on the third term of the angle rate equation.

For sufficiently high orbits (generally at least 190 kilometers (100 nautical miles) in the case of Earth), aerodynamic force may be assumed to be negligible for relatively short term missions (though a small amount of drag may be present which results in decay of orbital energy over longer periods of time.)

[9] This can be shown to result in the trajectory being ideally a conic section (circle, ellipse, parabola or hyperbola)[10] with the central body located at one focus.

The specific angular momentum of any conic orbit, h, is constant, and is equal to the product of radius and velocity at periapsis.

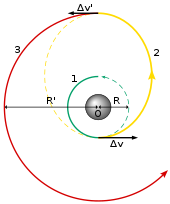

A slightly more complicated altitude change maneuver is the bi-elliptic transfer, which consists of two half-elliptic orbits; the first, posigrade burn sends the spacecraft into an arbitrarily high apoapsis chosen at some point

Vehicles sent on lunar or planetary missions are generally not launched by direct injection to departure trajectory, but first put into a low Earth parking orbit; this allows the flexibility of a bigger launch window and more time for checking that the vehicle is in proper condition for the flight.

[19] An accurate solution of the trajectory requires treatment as a three-body problem, but a preliminary estimate may be made using a patched conic approximation of orbits around the Earth and Moon, patched at the SOI point and taking into account the fact that the Moon is a revolving frame of reference around the Earth.

However, the rocket burn duration is usually long enough, and occurs during a sufficient change in flight path angle, that this is not very accurate.

It must be modeled as a non-impulsive maneuver, requiring integration by finite element analysis of the accelerations due to propulsive thrust and gravity to obtain velocity and flight path angle:[7]

Greater flexibility in lunar orbital or landing site coverage (at greater angles of lunar inclination) can be obtained by performing a plane change maneuver mid-flight; however, this takes away the free-return option, as the new plane would take the spacecraft's emergency return trajectory away from the Earth's atmospheric re-entry point, and leave the spacecraft in a high Earth orbit.

In the Apollo program, the retrograde lunar orbit insertion burn was performed at an altitude of approximately 110 kilometers (59 nautical miles) on the far side of the Moon.

[20] For each mission, the flight dynamics officer prepared 10 lunar orbit insertion solutions so the one could be chosen with the optimum (minimum) fuel burn and best met the mission requirements; this was uploaded to the spacecraft computer and had to be executed and monitored by the astronauts on the lunar far side, while they were out of radio contact with Earth.

For accurate mission calculations, the orbital elements of the planets must be obtained from an ephemeris,[21] such as that published by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

For the purpose of preliminary mission analysis and feasibility studies, certain simplified assumptions may be made to enable delta-v calculation with very small error:[24] Since interplanetary spacecraft spend a large period of time in heliocentric orbit between the planets, which are at relatively large distances away from each other, the patched-conic approximation is much more accurate for interplanetary trajectories than for translunar trajectories.

There is a great deal of variation with time of the velocity change required for a mission, because of the constantly varying relative positions of the planets.

Attitude control is maintained with respect to an inertial frame of reference or another entity (the celestial sphere, certain fields, nearby objects, etc.).

The attitude of a craft is described by angles relative to three mutually perpendicular axes of rotation, referred to as roll, pitch, and yaw.

The three principal moments of inertia Ix, Iy, and Iz about the roll, pitch and yaw axes, are determined through the vehicle's center of mass.

The control torque for a launch vehicle is sometimes provided aerodynamically by movable fins, and usually by mounting the engines on gimbals to vector the thrust around the center of mass.

Torque is frequently applied to spacecraft, operating absent aerodynamic forces, by a reaction control system, a set of thrusters located about the vehicle.