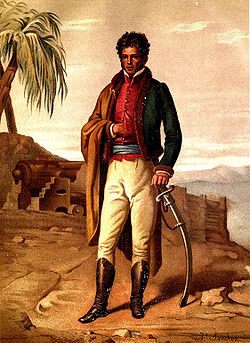

Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña[2] (Spanish: [biˈsente raˈmoŋ ɡeˈreɾo]; baptized 10 August 1782 – 14 February 1831) was a Mexican military officer from 1810–1821 and a statesman who became the nation's second president in 1829.

[4] Vicente Guerrero was born in Tixtla, a town approximately 100 kilometers inland from the port of Acapulco, in the Sierra Madre del Sur.

His father's family included landowners, affluent farmers, traders with broad business connections in Southern Mexico, members of the Spanish militia, gunsmiths, and cannon manufacturers.

Fellow insurgent José María Morelos described Guerrero as a "young man with bronzed or tanned skin (broncineo in Spanish), tall and strong, with an aquiline nose, bright, light-colored eyes, and prominent sideburns".

In December 1810, Guerrero enlisted in José María Morelos's insurgent army in southern Mexico, beginning his career as a revolutionary leader.

[citation needed] In 1810, Guerrero joined in the early revolt against Spain, first fighting in the forces of secular priest José María Morelos.

[9] Guerrero distinguished himself in the Battle of Izúcar, in February 1812, and had achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel when Oaxaca was claimed by rebels in November 1812.

[8] In March 1816, According to the Historian William Sprague Vicente Guerrero, after the death of Morelos and Juan Nepomuceno Rosains had quit the revolution taking a Spanish pardon, Guerrero had no commander thus Guadalupe Victoria and Isidoro Montes de Oca, gave him the position of "Commander in Chief" of the rebel troops.

He won victories at Ajuchitán, Santa Fe, Tetela del Río, Huetamo, Tlalchapa, and Cuautlotitlán, regions of southern Mexico that were very familiar to him.

Conservatives in Mexico, including the Catholic hierarchy, began to conclude that continued allegiance to Spain would undermine their position and opted for independence to maintain their control.

The Plan of Iguala proclaimed independence, called for a constitutional monarchy and the continued place of the Roman Catholic Church, and abolished the formal casta system of racial classification.

Vicente Guerrero advocated for all people in Mexico to receive equal protections under the law without regards to race and refused to agree to any alternative.

[11] Clause 12 was incorporated into the plan: "All inhabitants... without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens... with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues.

In January 1823, Guerrero, along with Nicolás Bravo, rebelled against Iturbide, returning to southern Mexico to raise rebellion, according to some assessments because their careers had been blocked by the emperor.

Gómez Pedraza was the candidate of the "Impartials", composed of Yorkinos concerned about the radicalism of Guerrero and Scottish Rite Masons (Escocés), who sought a new political party.

His violent temper renders him difficult to control, and therefore I consider Zavala's presence here indispensably necessary, as he possesses great influence over the general.

"A free state protects the arts, industry, science and trade; and the only prizes virtue and merit: if we want to acquire the latter, let's do it cultivating the fields, the sciences, and all that can facilitate the sustenance and entertainment of men: let's do this in such a way that we will not be a burden for the nation, just the opposite, in a way that we will satisfy her needs, helping her to support her charge and giving relief to the distraught of humanity: with this we will also achieve abundant wealth for the nation, making her prosper in all aspects.

[21] In November 1828 in Mexico City, Guerrero supporters took control of the Accordada, a former prison transformed into an armory, and days of fighting occurred in the capital.

[26] Some creole elites (American-born whites of Spanish heritage) were alarmed by Guerrero as president, a group that liberal Lorenzo de Zavala disparagingly called "the new Mexican aristocracy".

[27] Guerrero set about creating a cabinet of liberals, but his government already encountered serious problems, including its very legitimacy, since president-elect Gómez Pedraza had resigned under pressure.

Guerrero called for public schools, land title reforms, industry and trade development, and other programs of a liberal nature.

"This is the most liberal and munificent Government on earth to emigrants – after being here one year you will oppose a change even to Uncle Sam"During Guerrero's presidency, the Spanish tried to reconquer Mexico but were defeated at the Battle of Tampico.

Guerrero had strength in the hot coastal regions of the Costa Grande and Tierra Caliente, with mixed race populations that had been mobilized during the insurgency for independence.

[30] The war in the south might have continued even longer, but ended in what one historian has called "the most shocking single event in the history of the first republic: the capture of Guerrero in Acapulco through an act of betrayal and his execution a month later.

His death did mark the dissolution of the rebellion in southern Mexico, but those politicians involved in his execution paid a lasting price to their reputations.

[31] Many Mexicans saw Guerrero as the "martyr of Cuilapam" and his execution was deemed by the liberal newspaper El Federalista Mexicano "judicial murder".

The two conservative cabinet members considered most culpable for Guerrero's execution, Lucas Alamán and Secretary of War José Antonio Facio, "spent the rest of their lives defending themselves from the charge that they were responsible for the ultimate betrayal in the history of the first republic, that is, that they had arranged not just for the service of Picaluga's ship but specifically for his capture of Guerrero.

"[30] Historian Jan Bazant speculates as to why Guerrero was executed rather than sent into exile, as Iturbide had been, as well as Antonio López de Santa Anna, and long-time dictator of late-nineteenth century Mexico, Porfirio Díaz.

I have always had respect for my father, but my country comes first.”[9][34] These words contribute to mythology surrounding Guerrero that historian Theodore Vincent argues makes up Mexican culture.