Spanish assault on French Florida

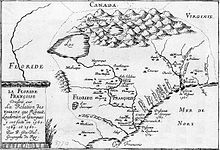

The Spanish assault on French Florida began as part of imperial Spain's geopolitical strategy of developing colonies in the New World to protect its claimed territories against incursions by other European powers.

The political and religious enmities that existed between the Catholics and Huguenots[6] of France resulted in the attempt by Jean Ribault in February 1562 to settle a colony at Charlesfort on Port Royal Sound,[7] and the subsequent arrival of René Goulaine de Laudonnière at Fort Caroline, on the St. Johns River in June 1564.

However, Spanish attempts to establish a lasting presence in La Florida failed until September 1565, when Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St. Augustine about 30 miles south of Fort Caroline.

While Spain's rivals did not seriously challenge its claim to the vast territory for decades, a French force attacked and destroyed Fort Mateo in 1568, and English pirates and privateers regularly raided St. Augustine over the next century.

[22] Laudonnière, in the meantime, had been driven to desperation by famine,[23] although surrounded by waters abounding with fish and shellfish, and had been partially relieved by the arrival of the ship of the English sea dog and slave trader Sir John Hawkins, who furnished him a vessel to return to France.

[27] Meanwhile, Menéndez, after gathering his men to hear Mass around a temporary altar, traced the outline of the first Spanish fort to be built in St. Augustine, at a spot located near the site of the present Castillo de San Marcos.

On Tuesday, September 4, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, adelantado of La Florida, set sail from the harbor of what was to become the presidio of St. Augustine, and coasting north, came upon four vessels lying at anchor off the mouth of a river.

"[37] In the silence which prevailed while the parley was in progress, those aboard his ship heard a boat put out from one of the Frenchmen, carrying a message to their flagship and the reply of the French commander, "I am the Admiral, I will die first," from which they inferred that it was a proposition to surrender.

The Frenchmen had also heard the signal and, taking advantage of the momentary pause, cut their cables, passed right through the Spanish fleet, and fled, three vessels turning to the north and the other to the south, with the Spaniards in hot pursuit.

Menéndez feared Ribault would return, attack his fleet while he was unloading, and perhaps capture the San Pelayo, which carried the major part of his supplies and ammunition; he was also anxious to send two of his sloops back to Havana for reinforcements.

On leaving Cadiz, Menéndez had been informed by the Seville Inquisition that there were "Lutherans" in his fleet, and, having made an investigation, he discovered and seized twenty-five of them, whom he dispatched in the two vessels to Santo Domingo or Puerto Rico, to be returned to Spain.

They killed the captain, master, and all the Catholics aboard, and made their way past Spain, France, and Flanders, to the coast of Denmark,[56] where the San Pelayo was wrecked and the heretics appear finally to have escaped.

Laudonnière, who was familiar with the sudden storms to which the region was subject during September, disapproved of his plan, pointing out the danger to which the French ships would be exposed of being driven out to sea, and the defenseless condition in which Fort Caroline would be left.

Although food stores were depleted, as Ribault had carried off two of his boats with the meal which had been left over after making the biscuit for the return to France, and although Laudonnière himself was reduced to the rations of a common soldier, he yet commanded the allowance to be increased in order to lift the morale of his men.

The tide was out and his boats so loaded that only by great skill was he able to cross it with his sloop, and escape; for the French, who had at once attempted to prevent his landing and thus to capture his cannon and the supplies he had on board, got so close to him, that they hailed him, and summoned him to surrender, promising that no harm should befall him.

If his approach was discovered, he proposed, on reaching the margin of the woods which surrounded the open meadow where it stood, to display the banners in such a way as to lead the French to believe that his force was two thousand strong.

A picked company of twenty Asturians and Basques under their captain, Martin de Ochoa, led the way armed with axes with which they blazed a path through the forest and swamps for the men behind them,[72] guided by Menéndez who carried a compass to find the right direction.

Inside Fort Caroline, La Vigne was keeping watch with his company, but taking pity on his sentinels, wet and fatigued with the heavy rain, he let them leave their stations with the approach of day, and finally he himself retired to his own quarters.

[84] Jacques le Moyne, the artist, still lame in one leg from a wound he had received in the campaign against the Timucua chief Outina,[85] was roused from his sleep by the outcries and sound of blows proceeding from the courtyard.

Menéndez had remained outside urging his troops on to the attack, but when he saw a sufficient number of them advance, he ran to the front, shouting out that under pain of death no women were to be killed, nor any boys less than fifteen years of age.

At this the Frenchmen who remained alive entirely lost heart, and while the main body of the Spaniards were going through the quarters, killing the old, the sick, and the infirm, quite a number of the French succeeded in getting over the palisade and escaping.

Receiving no response, he sent Jean Francois to the Pearl with the proposal that the French should have a safe-conduct to return to France with the women and children in any one vessel they should select, provided they would surrender their remaining ships and all of their armament.

Hearing from the carpenter, Jean de Hais, who had escaped in a small boat,[90] of the taking of the fort, Jacques Ribault decided to remain a little longer in the river to see if he might save any of his compatriots.

About half a dozen drummers and trumpeters were held as prisoners, of which number was Jean Memyn, who later wrote a short account of his experiences; fifty women and children were captured, and the balance of the garrison got away.

Throughout the attack the storm had continued and the rain had poured down, so that it was no small comfort to the weary soldiers when Jean Francois pointed out to them the storehouse, where they all obtained dry clothes, and where a ration of bread and wine with lard and pork was served out to each of them.

They passed the night in a grove of trees in view of the sea, and the following morning, as they were struggling through a large swamp, they observed some men half hidden by the vegetation, whom they took to be a party of Spaniards come down to cut them off.

But he first sent the camp master with a party of fifty men to look for those who had escaped over the palisade, and to reconnoitre the French vessels which were still lying in the river,[101] and whom he suspected of remaining there in order to rescue their compatriots.

On September 19, three days after Menéndez had departed from St. Augustine and was encamped with his troops near Fort Caroline, a force of twenty men was sent to his relief with supplies of bread and wine and cheese, but the settlement remained without further news of him.

When the French Huguenot leader, Jean Ribault, learned of the Spanish settlement, he also decided on a swift assault and sailed south from Fort Caroline with most of his troops to search for St. Augustine.

Menéndez was chagrined upon his return to Florida; however, he maintained order among his troops, and after fortifying St. Augustine as the headquarters of the Spanish colony, sailed home to use his influence in the royal court for their welfare.