Spanish conquest of Honduras

[3] The highest mountain range in the highlands is the Sierra del Merendón; it runs from the southwest to the northeast and reaches a maximum altitude of 2,850 metres (9,350 ft) above mean sea level at Cerro Las Minas.

[9] Much of Honduras belonged to the so-called Intermediate Area, generally viewed as a region of lesser cultural development located between Mesoamerica and the Andean civilizations of South America.

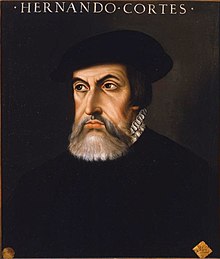

[22] The Spanish heard rumours of the rich empire of the Aztecs on the mainland to the west of their Caribbean island settlements and, in 1519, Hernán Cortés set sail to explore the Mexican coast.

[26] In 1508, the Caribbean coast of Honduras was superficially explored by Spanish navigators Juan Díaz de Solís and Vicente Yáñez, but the focus of their expeditions lay further to the north.

[28] The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but instead a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of precious metals, land grants and provision of native labour.

[40] In the first half of the 16th century, towns were abandoned or moved for a variety of reasons, including native attacks, harsh conditions, and the spread of Old World diseases such as smallpox, measles, typhoid, yellow fever, and malaria.

Unlike in Mexico, where centralised indigenous power structures assisted swift conquest, there was no unified political organisation to overthrow; this hindered the incorporation of the territory into the Spanish Empire.

[62] González Dávila landed on the north coast, with authorisation from the king to conquer Honduras, after having paid the royal fifth of the proceeds from his campaigns in Panama and Nicaragua, a sum totalling 112,524 gold castellanos.

[81] When the land party arrived, although troubled by the desertion of López de Aguirre, they settled in Trujillo as planned,[88] The town was founded in May 1525, in the largest sheltered bay on the Caribbean coast of Central America.

The residents of Trujillo pleaded with Moreno for assistance, which he granted on condition that they renounced Cortés, accepted the jurisdiction of the Audiencia of Santo Domingo, and agreed to take Juan Ruano, one of Olid's former officers, as Chief Magistrate.

Moreno renamed Trujillo as Ascensión, and he sent messages to Hernández de Córdoba, who was in Nicaragua, asking him to renounce his loyalty to Pedrarias Dávila and pledge allegiance to Santo Domingo.

[92] He crossed the Dulce River to the settlement of Nito, somewhere on the Amatique Bay,[93] with about a dozen companions, where he found the near-starving remnants of Gil González Dávila's colonists, who received him joyfully.

[103] Rojas' party was attempting to expand Hernández de Córdoba's Nicaraguan territory; upon meeting native resistance his men began pillaging the district and enslaving the inhabitants.

[99] Upon receiving complaints from native informants, Cortés dispatched de Sandoval with ten cavalry to hand papers to Rojas, ordering him out of the territory, and to release any Indians and their goods that he had seized.

[103] Hernández de Córdoba sent a second expedition into Honduras, carrying letters to the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo and to the Crown, searching for a good location for a port on the Caribbean coast, to provide a link to Nicaragua.

Natives in the north launched an overwhelming assault upon Natividad de Nuesta Señora near Puerto Caballos, forcing the Spanish there to hold up in a natural stronghold, and send a request for reinforcements to Saavedra, who was unable to spare any men to relieve them.

It was taking efforts to place Crown officials as governors, and creating colonial organisations such as the audiencias (courts) to impose absolute government over territories claimed by Spain.

[114] He hanged several indigenous leaders who had taken part in the attack on Natividad de Nuestra Señora, and imposed such harsh obligations upon the natives that they burned their villages and their crops and fled into the mountains.

The Ch'orti' fortifications were strong enough to hold the Spanish and their indigenous auxiliaries at bay for several days, but eventually they managed to cross the moat and breach the palisade, routing the defenders.

Less than a year after permission was given to Alvarado, then governor of Honduras and Higueras, Diego Alvítez, was given royal authorisation to pacify and colonise the Naco valley and the area around Puerto de Caballos.

[162] Gonzalo de Alvarado had been exploring the central region around Siguatepeque, the Tinto River and Yoro, successfully dealing with native resistance and collecting supplies for San Pedro.

[164] Gonzalo de Alvarado and his men decided to remain; the area was apparently well-populated enough to provide worthwhile tribute, and the existence of precious metal deposits in the region had already been established by earlier forays.

Alvarado had also encouraged the enslavement of natives that fought against the Spanish, and their subsequent sale, as well as general harsh treatment of the indigenous population; this produced considerable resentment among the Indians, and left them susceptible to rebellion.

Continued slave raids, and ferocious treatment at the hands of the Achi Maya auxiliaries increased their hatred and resistance, and many Indians abandoned their settlements and fled to the mountains and forests.

[172] Cáceres launched a coup at dawn early in 1537, entered Gracias a Dios with twenty well-armed soldiers and imprisoned the town council, including Gonzalo de Alvarado.

[172] Francisco de Montejo travelled overland from Mexico with his considerable expedition, which included soldiers, Mexican auxiliaries, provisions and livestock; he sent a smaller detachment by sea, with additional supplies as well as his family and household.

The moderation of Montejo's actions encouraged considerable numbers of natives to return to their villages, especially around Gracias a Dios, and the encomienda system began to function as was intended, which greatly alleviated the constant struggle for provisions.

[183] After Pedro de Alvarado's brutal suppression of western Honduras, indigenous resistance against the Spanish had coalesced around the Lenca warleader Lempira,[nb 6][184] who was reputed to have led an army of 30,000 native warriors.

Although the immediate threat was limited to the region close to the Peñol de Cerquín, the Spanish realised that the rebellion at such a strong fortress was a powerful symbol of native independence throughout Higueras.

The campaign in the Comayagua valley proved difficult; the Spanish were hindered by the broken terrain, while the natives were still determined to resist and had established fortified mountaintops in a similar fashion to the Peñol de Cerquín.