Spanish conquest of the Muisca

For the main part self-sufficient in their well-organised economy, the Muisca traded with the European conquistadors valuable products as gold, tumbaga (a copper-silver-gold alloy), and emeralds with their neighbouring indigenous groups.

The economy of the Muisca was rooted in their agriculture with main products maize, yuca, potatoes, and various other cultivations elaborated on elevated fields (in their language called tá).

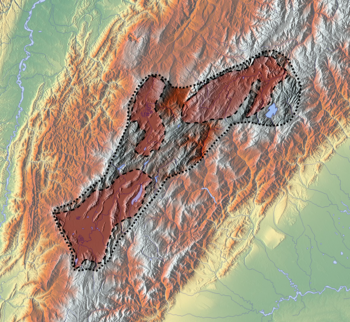

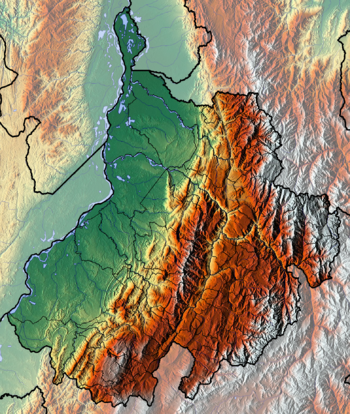

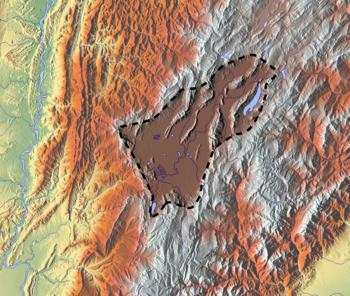

The main part of the Muisca civilisation was concentrated on the Bogotá savanna, a flat high plain in the Eastern Ranges of the Andes, far away from the Caribbean coast.

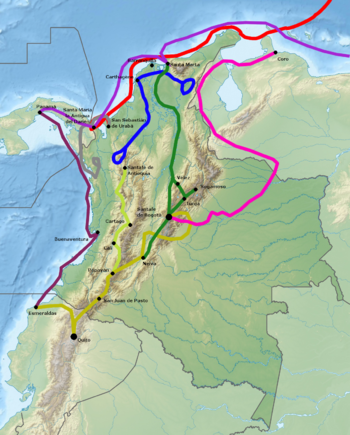

A delegation of more than 900 men left the tropical city of Santa Marta and went on a harsh expedition through the heartlands of Colombia in search of El Dorado and the civilisation that produced all this precious gold.

That same month, on August 20, the zipa who succeeded his brother Tisquesusa upon his death; Sagipa, allied with the Spanish to fight the Panche, eternal enemies of the Muisca in the southwest.

Two other expeditions that were taking place at the same time; of De Belalcázar from the south and Federmann from the east, reached the newly founded capital and the three leaders embarked in May 1539 on a ship on the Magdalena River that took them to Cartagena and from there back to Spain.

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada had installed his younger brother Hernán as new governor of Bogotá and the latter organised new conquest campaigns in search of El Dorado during the second half of 1539 and 1540.

[21][22] At the site, the remains of 2200 individual people, 274 complete ceramic pots, stone tools, seeds of cotton, maize, beans and curuba, 634 fragmented and intact spindles and 100 tunjos not used for offerings were found.

[28] Other than the other great civilisations of pre-Columbian Americas, such as the Aztec, Maya and Inca, the people did not construct large stone architecture, yet built their bohíos and temples of clay, wooden poles and reed in small communities on artificially elevated areas.

The festivities of this ritual were surrounded with music, singing and dances and accompanied by large quantities of chicha, the indigenous alcoholic beverage made of fermented maize.

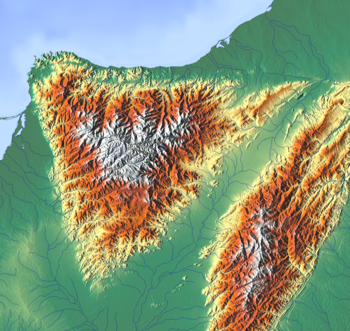

[43] The legend of El Dorado, the fine goldworking, abundance of salt and emeralds, and the advanced status of the Muisca society formed the main motive for the Spanish conquistadors to leave the relative safety of Santa Marta and commence the strenuous expedition inland.

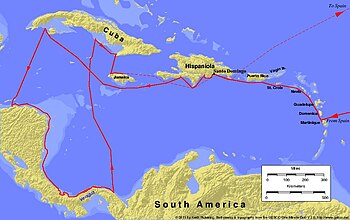

De Ojeda's second voyage commenced in January 1502 and following the same route as his first, he landed on the Colombian mainland on May 3, 1502, founding the first colony in South America; Santa Cruz today part of Bahia Honda.

The indigenous Wayuu resisted ferociously and the Spanish explorers couldn't find enough food and fresh water in the barren desert region to maintain the colony.

On April 6, 1536, triggered by the stories of the mythical "City of Gold" El Dorado, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada organised two groups of conquistadors to set foot towards the inner highlands of the Colombian Andes, as first European explorers.

The messengers returned with sad news; the majority of boats had shipwrecked in the mouth of the Magdalena and the soldiers who survived and made it onshore fell prey to the poisoned arrows of the indigenous groups and the crocodiles along the river.

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada was convinced they would reach the lands full of gold they heard about at the Caribbean coast and motivated his delegation of soldiers, that at this time had an average age of 27 years old, to walk on.

Early 1537, after passing through Aguada, the expedition reached Chipatá, the first settlement of the Muisca, where father Juan Domingo de las Casas held his first sermon.

[1][70] The climate of Chipatá, at 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) altitude, was much more pleasant than the hot lower valleys of the Opón River and Gonzalo decided to stay for five months in the town to allow his soldiers to rest and regain strength.

Using the enslaved indigenous people of the coast who understood forms of Chibcha, Gonzalo and Hernán were informed where the civilisation producing those fine mantles and salt was located.

[1] The Spanish settlers, still around 150 kilometres (93 mi) away from the southern Muisca capital Bacatá, continued south and reached the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, where they marched through the Ubaté-Chiquinquirá Valley, passing through Barbosa, close to Saboyá.

When the troops of de Quesada arrived in Nemocón, the local inhabitants brought them food like deer, pigeons, rabbits, guinea pigs, beans, tubers, and other aliments, new to the Spanish.

[85] When Tisquesusa retreated in his fort in Cajicá he allegedly told his men he would not be able to combat against the strong Spanish army in possession of weapons that produced "thunder and lightning".

Legend tells that he dropped his weapons and fell in love with her, eventually marrying the sister of Tisquesusa and they were baptised in Usaquén, meaning "Land of the Sun" in Muysccubun.

Without having found El Dorado, three years after his departure from Santa Marta, in mid May 1539, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada returned to the Caribbean coast, to sail to Spain from Cartagena.

[112] On December 15, 1539, another Spanish captain coming from the south after conquering Peru and the Kingdom of Quito as part of the expedition by De Belalcázar, Baltasar Maldonado, entered the territories of Tundama and offered him a peace proposal if he would surrender.

[112][113][114] Maldonado, enforced with 2000 yanakunas; indigenous prisoners of war from Peru and submitted people from Bacatá and Ramiriquí, was accompanied by the Muisca whose ears and hand had been cut off by Tundama.

The rich mineral resources of the Altiplano had to be extracted, the agriculture was quickly reformed, a system of encomiendas was installed and a main concern of the Spanish was the evangelisation of the Muisca.

[120] The second bishop of Santafé, Luis Zapata de Cárdenas, intensified the aggressive policies against the indigenous religious practices and ordered the burnings of their sacred sites.

[124] Also the idea that the Muisca were a war-like people has been revised in the modern age, pointing to their successful trading, that even the Spanish scholars, such as first bishop of Bogotá Juan de los Barrios, have praised in their writings.

The word for "one" in Muysccubun is ata, while in the closest related Chibchan languages of Colombia "one" translates as úbistia (Uwa), intok (Barí) and ti-tasu or nyé (Chimila).

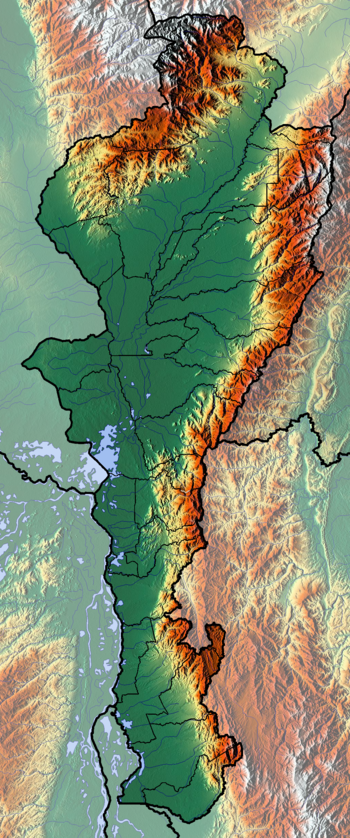

The conquest expedition led by De Quesada followed its course south on the right bank (east) from Tamalameque (where the river curves west) to Barrancabermeja ascending towards Muisca territory

Sebastián de Belalcázar (1514–1539)

Jorge Robledo

Juan de Ampudia

Gaspar de Rodas

Baltasar Maldonado

First coastal exploration

Alonso de Ojeda (1509–10)

Francisco Pizarro

Foundation of Santa Marta

Rodrigo de Bastidas (1525)

Juan de Céspedes

First conquest expedition

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada (1536–1539)

Hernán Pérez de Quesada

Martín Galeano

Ortún Velázquez de Velasco

Juan de San Martín

Gonzalo Suárez Rendón

Bartolomé Camacho Zambrano

Antonio de Lebrija

Lázaro Fonte

Juan de Céspedes

Gonzalo Macías

Juan Maldonado

Expedition from the east

Nikolaus Federmann (1537–1539)

Miguel Holguín y Figueroa

Quest for El Dorado I

Hernán Pérez de Quesada (1539–1541)

Baltasar Maldonado

Lázaro Fonte

Quest for El Dorado II

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada (1569–1572)

Gonzalo Macías

Juan Maldonado

Legend :

• Leader – minor captain

It was destroyed by fire from torches brought at night by two soldiers from the team of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada.

A reconstruction has been built in the Archaeology Museum of Sogamoso

by Agustín Codazzi , 1890

Rainbow god Cuchavira appears above the city