Spanish philosophy

As the Latin Hispania was considered to include the entire Iberian Peninsula, he is traditionally and usually identified with the medieval Portuguese scholar and ecclesiastic Peter Juliani, who was elected Pope John XXI in 1276.

At Majorca and in Catalonia generally (and from there to Castile and southern Italy), the Lullist movement had connotations of religious radicalism: it was more diffuse and more in tune with the needs of the new spirituality (as is shown by the great intellectual work performed in favour of the Immaculate Conception, between the 14th and 15th centuries).

The situation was different in Catalonia where a real Lullist school was established at Barcelona, and in Majorca where as early as c. 1453 Lullism was taught by friar Joan Llobet at Randa.

After his death and with the accession of John XXII, new attacks began on his work, which was condemned by a provincial court at Tarragona in 1316, even though, since the time of Boniface VIII, the pope had reserved the examination of Arnold's writings for himself.

Its exponents turned to medieval High Scholasticism—personified by Thomas Aquinas—in order to solve philosophical problems with reference to the ancient classics such as Aristotle and in harmony with Church doctrine, and thus to prove the compatibility of reason and Christian faith.

Even though there are a number of points of contact with the theological disputes of the day, the School of Salamanca is fundamentally distinct from the Counter-Reformation and other sixteenth-century movements in Spanish philosophy, such as mysticism.

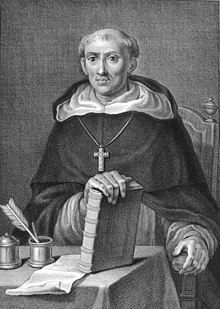

At Trent, he led the council away from compromise with Protestantism and toward its reaffirmation of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, transubstantiation, the sacrificial dimension of the Mass, and private auricular confession.

Ever faithful to his mentor, Vitoria—who was one of the principal defenders of the rights of the indigenous peoples of the Americas against their Spanish conquerors—Cano became a formidable opponent of those who considered the Indians inferior beings and "natural" slaves.

Cano's chief opponent in this controversy was Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, chaplain and official chronicler to Emperor Charles V. When Sepúlveda defended the right of Charles to wage war upon and enslave the Indians in Democrates secundus sive de justis causis belli apud Indos (1544), Cano ensured the book's condemnation by the faculties of Salamanca and Alcalá.

Moreover, Sepúlveda's defeat at the hands of Cano and other Dominicans in a debate held in Valladolid in 1550 led to the enactment of laws protecting the rights of native peoples in the New World.

At Rome, Cano was accused of challenging pontifical authority, and though he was twice elected provincial of Castile by his fellow Dominicans, Pope Paul IV refused to confirm him.

Cano and other representatives of the School of Salamanca sought to enlarge the scope of theology by turning away from the abstract dialectics of Scholasticism and by placing a greater emphasis on ethical concerns.

Like all Thomists, Cano defended the capacity of humans to understand or even intuit the truths revealed by God, and he engaged in an exegesis of the ius naturale, or law of nature.

Aimed squarely against the paradigm of sola scriptura, Cano's theological method sought religious truth in a variety of sources, which included not just the Bible but also oral tradition; the pronouncements of councils, bishops, and popes; the writings of the Fathers; and even the teachings of pagan philosophers and the testimony of human history as interpreted by natural reason.

Cano's method was enthusiastically embraced by post-Tridentine theologians, and was taken to greater heights by some of his Jesuit followers in the School of Salamanca; four centuries later such influential thinkers as Joseph Maréchal and Karl Rahner continued to build on its foundations.

Molina began a commentary on part I of Thomas Aquinas's Summa theologiae, but his manuscript was so extensive on questions concerning divine foreknowledge, providence, and predestination, all in relation to free choice, that he lifted his treatment of these and brought out a separate work, the Concordia liberi arbitrii cum Gratiæ donis, divina præscientia, providentia, prædestinatione et reprobatione (1588).

Against this view, the Thomists of Salamanca, headed by Domingo Báñez, denied such intermediate divine knowledge and held that predestination is prior to foreseen human meritorious actions.

His last years at Alcalá de Henares were marked by a bitter rivalry with his fellow Jesuit, the more flamboyant Gabriel Vázquez, so Suárez was happy to move to Salamanca, where he taught and wrote until 1597.

In choosing to write on the Summa rather than Peter Lombard's Sententiae, Suárez was following the precedent set a half century earlier by Francisco de Vitoria at Salamanca and thereby contributed to making Thomism central to revived scholasticism, even though he often departed from the teachings of Thomas on particular issues.

His main contribution to anti-Protestant polemics was his long Defensio Fidei catholicae et Apostolicae adversus Anglicanae sectae errores (Coimbra, 1613, partial English translation in 1944), which was largely directed against the oath that King James I demanded from his Catholic subjects.

Pérez took over from his master Benito de Robles the general project of ‘staying close to Augustine in metaphysical matters’ (rebus metaphysicis proximum fuisse Augustino; In primam 87a).

An entire school of thought called ‘Incompatibilism’ (Incompossibilistae) emerged from Pérez's insights and led to numerous discussions in Spanish and also Central European colleges.

Following again Augustine (and his master Pedro Hurtado de Mendoza), he underlined that God must be considered both as the creator of essences and existences in the world (auctor essentiarum).

Pérez's main originality lies in the way he tried to express classical insights of Augustine in the highly sophisticated language of early modern Aristotelian scholasticism.

It also meant the progressive abandoning of the rationalist and naturalistic conceptions of faith developed by John de Lugo and a victory of a new form of fideism which could again fully claim Augustine's authority.

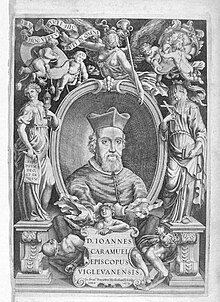

The practical axioms are founded in divine and human authority, and Caramuel treats them according to the Aristotelian table of categories (discussing for instance the quality and quantity of law).

Although educated in the Thomist tradition, Caramuel firmly believed in the humanist ideal of nullius addictus iurare in verba magistri (‘not to swear slavishly by the words of any master’).

He refused to be enrolled in a specific school of thought and felt free to choose among all the authorities that would best suit his project of constructing a renovated Christian philosophy.

Donoso was condemned by his enemies as a reactionary, but in the 20th century he has been reevaluated in Spain, Germany, and France as an accurate observer whose prophecies came true in many cases, in particular his awareness of socialism and of the future political role of Russia.

According to Karl Löwith, Donoso describes bourgeois society exactly in the same terms as Kierkegaard and Marx: as an undifferentiated class discutidora, without truth, passion, or heroism.