Western philosophy

The pre-Socratic philosophers were interested in cosmology (the nature and origin of the universe), while rejecting unargued fables in place for argued theory, i.e., dogma superseded reason, albeit in a rudimentary form.

The discovery of consonant intervals in music by the group enabled the concept of harmony to be established in philosophy, which suggested that opposites could together give rise to new things.

Parmenides argued that, unlike the other philosophers who believed the arche was transformed into multiple things, the world must be singular, unchanging and eternal, while anything suggesting the contrary was an illusion.

[5] Zeno of Elea formulated his famous paradoxes in order to support Parmenides' views about the illusion of plurality and change (in terms of motion), by demonstrating them to be impossible.

[11] This was also applied to issues of ethics, with Prodicus arguing that laws could not be taken seriously because they changed all the time, while Antiphon made the claim that conventional morality should only be followed when in society.

The Cyrenaics promoted a philosophy nearly opposite that of the Cynics, endorsing hedonism, holding that pleasure was the supreme good, especially immediate gratifications; and that people could only know their own experiences, beyond that truth was unknowable.

Aristotle wrote widely about topics of philosophical concern, including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, aesthetics, poetry, theater, music, rhetoric, politics, and logic.

[24] The ideal of 'living in accordance with nature' also continued, with this being seen as the way to eudaimonia, which in this case was identified as the freedom from fears and desires and required choosing how to respond to external circumstances, as the quality of life was seen as based on one's beliefs about it.

[30] After returning to Greece, Pyrrho started a new school of philosophy, Pyrrhonism, which taught that it is one's opinions about non-evident matters (i.e., dogma) that prevent one from attaining ataraxia.

[40] An influential school of thought was that of scholasticism, which is not so much a philosophy or a theology as a methodology, as it places a strong emphasis on dialectical reasoning to extend knowledge by inference and to resolve contradictions.

[28] Another important figure for scholasticism, Peter Abelard, extended this to nominalism, which states (in complete opposition to Plato) that universals were in fact just names given to characteristics shared by particulars.

[68] These trends first distinctively coalesce in Francis Bacon's call for a new, empirical program for expanding knowledge, and soon found massively influential form in the mechanical physics and rationalist metaphysics of René Descartes.

[69] Descartes's epistemology was based on a method called Cartesian doubt, whereby only the most certain belief could act as the foundation for further inquiry, with each step to further ideas being as cautious and clear as possible.

[77] George Berkeley agreed with empiricism, but instead of believing in an ultimate reality which created perceptions, argued in favour immaterialism and the world existing as a result of being perceived.

[81] The approximate end of the early modern period is most often identified with Immanuel Kant's systematic attempt to limit metaphysics, justify scientific knowledge, and reconcile both of these with morality and freedom.

Kant wrote his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) in an attempt to reconcile the conflicting approaches of rationalism and empiricism, and to establish a new groundwork for studying metaphysics.

Continuing his work, Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Schelling dispensed with belief in the independent existence of the world, and created a thoroughgoing idealist philosophy.

Late modern philosophy is usually considered to begin around the pivotal year of 1781, when Gotthold Ephraim Lessing died and Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason appeared.

[96] Whereas he believed the frustration of this will was the cause of suffering, Friedrich Nietzsche thought that the will to power was empowering, leading to growth and expansion, and therefore forming the basis of ethics.

[100] Logic began a period of its most significant advances since the inception of the discipline, as increasing mathematical precision opened entire fields of inference to formalization in the work of George Boole and Gottlob Frege.

The 20th century deals with the upheavals produced by a series of conflicts within philosophical discourse over the basis of knowledge, with classical certainties overthrown, and new social, economic, scientific and logical problems.

[130] A further advancement in the philosophy of science was made by Imre Lakatos, who argued that negative findings in individual tests did not falsify theories, but rather entire research programmes would eventually fail explain phenomena.

But the diversity of analytic philosophy from the 1970s onward defies easy generalization: the naturalism of Quine and his epigoni was in some precincts superseded by a "new metaphysics" of possible worlds, as in the influential work of David Lewis.

However, with the appearance of A Theory of Justice by John Rawls and Anarchy, State, and Utopia by Robert Nozick, analytic political philosophy acquired respectability.

Analytic philosophers have also shown depth in their investigations of aesthetics, with Roger Scruton, Nelson Goodman, Arthur Danto and others developing the subject to its current shape.

Phenomenologically oriented metaphysics undergirded existentialism—Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Albert Camus—and finally post-structuralism—Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard (best known for his articulation of postmodernism), Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida (best known for developing a form of semiotic analysis known as deconstruction).

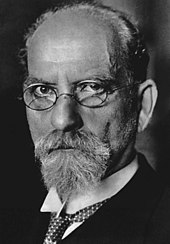

[180] Husserl published only a few works in his lifetime, which treat phenomenology mainly in abstract methodological terms; but he left an enormous quantity of unpublished concrete analyses.

Inaugurated by the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, structuralism sought to clarify systems of signs through analyzing the discourses they both limit and make possible.

Structuralists believed they could analyze systems from an external, objective standing, for example, but the poststructuralists argued that this is incorrect, that one cannot transcend structures and thus analysis is itself determined by what it examines.

Post-structuralism came to predominate from the 1970s onwards, including thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze and even Roland Barthes; it incorporated a critique of structuralism's limitations.