Transmutation of species

[1] The French Transformisme was a term used by Jean Baptiste Lamarck in 1809 for his theory, and other 18th and 19th century proponents of pre-Darwinian evolutionary ideas included Denis Diderot, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Erasmus Darwin, Robert Grant, and Robert Chambers, the anonymous author of the book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.

Opposition in the scientific community to these early theories of evolution, led by influential scientists like the anatomists Georges Cuvier and Richard Owen, and the geologist Charles Lyell, was intense.

The word evolved in a modern sense was first used in 1826 in an anonymous paper published in Robert Jameson's journal and evolution was a relative late-comer which can be seen in Herbert Spencer's Social Statics of 1851,[a] and at least one earlier example, but was not in general use until about 1865–70.

[5] In 1993, Muhammad Hamidullah described the ideas in lectures: [These books] state that God first created matter and invested it with energy for development.

[7] Robert Hooke proposed in a speech to the Royal Society in the late 17th century that species vary, change, and especially become extinct.

His “Discourse of Earthquakes” was based on comparisons made between fossils, especially the modern pearly nautilus and the curled shells of ammonites.

Although he believed in constant change, he took a very different approach from Diderot: chance and blind combinations of atoms, in de la Bretonne's opinion, were not the cause of transmutation.

De la Bretonne argued that all species had developed from more primitive organisms, and that nature aimed to reach perfection.

[9] Denis Diderot, chief editor of the Encyclopédie, spent his time poring over scientific theories attempting to explain rock strata and the diversity of fossils.

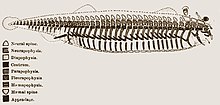

[8][10] Diderot drew from Leonardo da Vinci’s comparison of the leg structure of a human and a horse as proof of the interconnectivity of species.

His geological study of Derbyshire and the sea- shells and fossils which he found there helped him to come to the conclusion that complex life had developed from more primitive forms (Laniel-Musitelli).

Erasmus was an early proponent of what we now refer to as "adaptations", albeit through a different transformist mechanism – he argued that sexual reproduction could pass on acquired traits through the father’s contribution to the embryon.

Erasmus proposed that these acquired changes gradually altered the physical makeup of organisms as a result of the desires of plants and animals.

Krause explains Erasmus' motivations for arguing for the theory of descent, including Darwin's connection with and correspondence with Rousseau, which may have influenced how he saw the world.

It was this secondary mechanism of adaptation through the inheritance of acquired characteristics that became closely associated with his name and would influence discussions of evolution into the 20th century.

Grant developed Lamarck's and Erasmus Darwin's ideas of transmutation and evolutionism, investigating homology to prove common descent.

[18][19] The computing pioneer Charles Babbage published his unofficial Ninth Bridgewater Treatise in 1837, putting forward the thesis that God had the omnipotence and foresight to create as a divine legislator, making laws (or programs) which then produced species at the appropriate times, rather than continually interfering with ad hoc miracles each time a new species was required.

In this sense it was less completely materialistic than the ideas of radicals like Robert Grant, but its implication that humans were just the last step in the ascent of animal life incensed many conservative thinkers.

Both conservatives like Adam Sedgwick, and radical materialists like Thomas Henry Huxley, who disliked Chambers' implications of preordained progress, were able to find scientific inaccuracies in the book that they could disparage.

However, the high profile of the public debate over Vestiges, with its depiction of evolution as a progressive process, and its popular success, would greatly influence the perception of Darwin's theory a decade later.

[23] The proponents of transmutation were almost all inclined to Deism—the idea, popular among many 18th century Western intellectuals that God had initially created the universe, but then left it to operate and develop through natural law rather than through divine intervention.

Thinkers like Erasmus Darwin saw the transmutation of species as part of this development of the world through natural law, which they saw as a challenge to traditional Christianity.

The strength of Cuvier's arguments and his reputation as a leading scientist helped keep transmutational ideas out of the scientific mainstream for decades.

Idealists such as Louis Agassiz and Richard Owen believed that each species was fixed and unchangeable because it represented an idea in the mind of the creator.

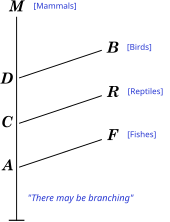

Owen developed the idea of "archetypes" in the divine mind that would produce a sequence of species related by anatomical homologies, such as vertebrate limbs.