Speculum Maius

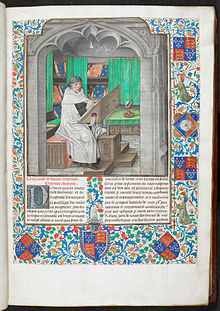

The Speculum Maius or Majus[1] (Latin: "The Greater Mirror") was a major encyclopedia of the Middle Ages written by Vincent of Beauvais in the 13th century.

All the printed editions of the Speculum Maius include this fourth part, which is mainly compiled from Thomas Aquinas, Stephen de Bourbon, and a few other contemporary writers[1] by anonymous fourteenth century Dominicans.

Isidore's influence is explicitly referenced by Vincent's prologue and can be seen in some minor forms of organization as well as the stylistic brevity used to describe the branches of knowledge.

The second part, The Mirror of Doctrine, Education, or Learning, in seventeen books and 2,374 chapters, is intended to be a practical manual for the student and the official alike; and, to fulfil this object, it treats of the mechanic arts of life as well as the subtleties of the scholar, the duties of the prince and the tactics of the general.

It treats of logic, rhetoric, poetry, geometry, astronomy, the human instincts and passions, education, the industrial and mechanical arts, anatomy, surgery and medicine, jurisprudence and the administration of justice.

[16] One remarkable feature of The Mirror of History is Vincent's constant habit of devoting several chapters to selections from the writings of each great author, whether sacred or profane, as he mentions him in the course of his work.

Four of the medieval historians from whom he quotes most frequently are Sigebert of Gembloux, Hugh of Fleury, Helinand of Froidmont, and William of Malmesbury, whom he uses for Continental as well as for English history.

[8] The number of writers quoted by Vincent is substantial: in the Speculum Maius[dubious – discuss] alone no less than 350 distinct works are cited, and to these must be added at least 100 more for the other two sections.

[25] Beyond the labour involved in copying manuscripts, one historian has argued that such separation of the Speculum Maius was due in part to medieval readers not recognizing the work to be organized as a whole.

[28] An eighteenth century writer remarked that this work was "a more-or-less worthless farrago of a clumsy plagiarist", one who merely extracted and compiled great swaths of text from other authors.

[29] A textual analysis of how the Speculum Maius integrated St. Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologiae shows that, while heavily extracted, the compiler made conscious decisions about the placement of parts and also redirected the meaning of certain passages.