Spelling of Shakespeare's name

In the Romantic and Victorian eras the spelling "Shakspere", as used in the poet's own signature, became more widely adopted in the belief that this was the most authentic version.

It later became a habit of writers who believed that someone else wrote the plays to use different spellings when they were referring to the "real" playwright and to the man from Stratford upon Avon.

[3] Though not considered genuine, there is a signature on the fly-leaf of a copy of John Florio's translation of the works of Montaigne, which reads "Willm.

[6] Critics of Kathman's approach have pointed out that it is skewed by repetitions of a spelling in the same document, gives each occurrence the same statistical weight irrespective of context, and does not adequately take historical and chronological factors into account.

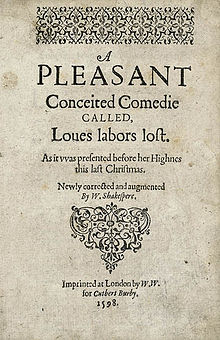

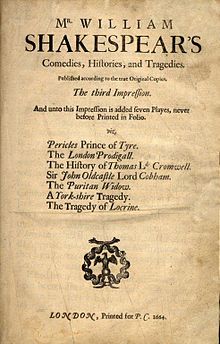

[6] It is spelled this way in the first quartos of The Merchant of Venice (1600), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1600), Much Ado About Nothing (1600), The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), Pericles, Prince of Tyre (1609), Troilus and Cressida (1609), Othello (1622).

[10] James S. Shapiro argues that Shakespeare's name caused difficulties for typesetters, and that is one reason why the form with the "e" in the centre is most commonly used, and why it is sometimes hyphenated.

Pope's rival Lewis Theobald retained it in his edition, Shakespeare Restored (1726), which pointedly rejected attempts to modernise and sanitise the original works.

[13] Archival material relating to Shakespeare was first identified by 18th-century scholars, most notably Edmond Malone, who recorded variations in the spelling of the name.

Malone declared a preference for the spelling "Shakspeare", using it in his major publications including his 1790 sixteen-volume edition of the complete works of the playwright.

[13] The antiquarian Joseph Hunter was the first to publish all known variations of the spelling of the name, which he did in 1845 in his book Illustrations of the Life, Studies, and Writings of Shakespeare.

He gives an account of what was known at the time of the history of the name of Shakespeare, and lists all its variant forms, including the most idiosyncratic instances such as "Shagsper" and "Saxpere".

Kathman argues that while it is possible that different pronunciations existed, there is no good reason to think so on the basis of spelling variations.

[6] According to Hunter it was in 1785 that the antiquarian John Pinkerton first revived the spelling "Shakspere" in the belief that this was the correct form as "traced by the poet's own hand" in his signatures.

[19] However, a later scholar identified a reference in The Gentleman's Magazine in 1784 to the deplorable "new fashion of writing Shakespeare's name SHAKSPERE", which suggests that the trend had been emerging since Steevens published facsimiles of the signatures in 1778.

The "Shakspere" spelling was quickly adopted by a number of writers and in 1788 was given official status by the London publisher Bell in its editions of the plays.

[13] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who published a large quantity of influential literature on the playwright, used both this and the "Shakspeare" spelling.

There was a heated debate in 1787, followed by another in 1840 when the spelling was promoted in a book by Frederic Madden, who insisted that new manuscript evidence proved that the poet always wrote his name "Shakspere".

Isaac D'Israeli wrote a strongly worded letter condemning this spelling as a "barbaric curt shock".

There followed a lengthy correspondence, mainly between John Bruce, who insisted on "Shakspere" because "a man's own mode of spelling his own name ought to be followed" and John William Burgon, who argued that "names are to be spelt as they are spelt in the printed books of the majority of well-educated persons", insisting that this rule authorised the spelling "Shakspeare".

Albert Richard Smith in the satirical magazine The Month claimed that the controversy was finally "set to rest" by the discovery of a manuscript which proved that the spelling changed with the weather, "When the sun shone he made his 'A's, / When wet he took his 'E's.

"[23] In 1879 The New York Times published an article on the dispute, reporting on a pamphlet by James Halliwell-Phillipps attacking the "Shakspere" trend.

He also insisted that the spelling represents the proper pronunciation, evidenced by puns on the words "shake" and "spear" in Shakespeare's contemporaries.

Hunter also argued that the spelling should follow established pronunciation and pointed to the poems, stating that "we possess printed evidence tolerably uniform from the person himself" supporting "Shakespeare".

Although this form had been used occasionally in earlier publications, and other spellings continued to appear, from that point "Shakespeare" gained the dominance which it retains to this day.

[31] When the advocates of the Shakespeare authorship question began to claim that someone other than Shakespeare of Stratford wrote the plays, they drew on the fact that variant spellings existed to distinguish between the supposed pseudonym used by the hidden author and the name of the man born in Stratford, who is claimed to have acted as a "front man".

Gibson notes that outlandish spellings seem sometimes to be chosen purely for the purpose of ridiculing him, by making the name seem vulgar and rustic, a characteristic especially typical of Baconians such as Edwin Durning-Lawrence: This hatred [of the Stratford man] not only takes the form of violent abuse and the accusation of every kind of disreputable conduct, but also of the rather childish trick of hunting up all the most outlandish Elizabethan variations of the spelling of his name, and filling their pages with "Shagspur", "Shaxpers", and similar atrocities; while Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence concludes each chapter in his book with the legend "Bacon is Shakespeare" in block capitals.