Sperm whaling

As with all the species targeted, the thick layer of fat (blubber) was flensed (removed from the carcass) and rendered, either on the whaling ship itself, or at a shore station.

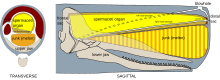

The liquid was removed from the spermaceti organ at sea, and stored separately from the rendered whale oil for processing back in port.

As the scope and size of the fleet increased so did the rig of the vessels change, as brigs, schooners, and finally ships and barks were introduced.

In the 19th century stubby, square-rigged ships (and later barks) dominated the fleet, being sent to the Pacific (the first being the British whaleship Emilia, in 1788),[11] the Indian Ocean (1780s), and as far away as the Japan grounds (1820; Syren) and the coast of Arabia (1820s), as well as Australia (1790s) and New Zealand (1790s).

The whale would then drag the boats (the famous "Nantucket sleighride") until it was too tired to resist, at which point the crew would lance it to death.

Although a properly harpooned sperm whale generally exhibited a fairly consistent pattern of attempting to flee underwater to the point of exhaustion (at which point it would surface and offer no further resistance), it was not uncommon for bull whales to become enraged and turn to attack pursuing whaleboats on the surface, particularly if it had already been wounded by repeated harpooning attempts.

A commonly reported tactic was for the whale to invert itself and violently thrash the surface of the water with its fluke, flipping and crushing nearby boats.

In the most famous example, on November 20, 1820 a huge bull sperm whale (purportedly 85-ft in length) rammed the 87-ft Nantucket whaler Essex twice, staving in the hull under the waterline and forcing the crew to abandon ship.

[16] The bull was unwounded and unprovoked at the time of the attack, but the crew of the Essex was in the process of hunting several smaller females from a nearby pod.

[17] Another proposed factor was the vibrations from repeated sledgehammer blows as the ship's hull was being repaired prior to the attack, which scientists suggest might have carried into the water and unintentionally mimicked the echolocation "clicks" that sperm whales generate to identify and communicate with each other.

The large and unusually aggressive bull had already attacked and chewed to pieces two pursuing whaleboats before eventually turning on the Ann Alexander itself and ramming it just above the keel at an estimated speed of 15 knots.

The bull (whose unusual aggressiveness was eventually blamed on old age and pain from disease) was later discovered floating on the surface, mortally injured and "full of wooden splinters" from the attack.

[18] American writer Herman Melville was inspired by the account of the Essex, and used some facts from the story, as well as his own eighteen-month experience as a sailor aboard a commercial whaler, to write his epic 1851 novel on the oil whaling industry, Moby Dick.

The sections in Moby Dick on the biology of the sperm whale were largely based on books by Thomas Beale (1839) and Frederick Bennett (1840).

[13] Sperm whales and other deep-sea species are still hunted from small open boats by hunters from two Indonesian villages, Lamalera and Lamakera.

[25] However, the recovery from the whaling years is a slow process, particularly in the South Pacific, where the toll on males of a breeding age was severe.