Drift whale

In historical sources, it is not always clear whether a given cetacean washed up alive or dead, but the term "drift whale" focuses on the benefits of its carcass – meat, blubber, fat, and other products – to the people who claimed it.

[9][10] Another obvious and visible cause of traumatic death is cetacean bycatch, i.e., entanglement with fishing gear, which kills tens of thousands each year, according to the International Whaling Commission.

[11] Other carcasses show no visible injury, and theories about why the animals died include the possibilities discussed for live strandings (especially active sonar) as well as illness and malnutrition.

Modern recreational beachcombers use knowledge of how storms, geography, ocean currents, and seasonal events determine the arrival and exposure of rare finds;[14][15] the same applies to those looking out for drift whales.

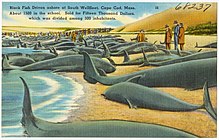

[19][20] A whale's massive carcass would provide a coastal community with considerable amounts of meat and fat, without the danger and effort of venturing onto the open ocean to harpoon a living leviathan.

[23] Two anthropologists, Thomas Talbot Waterman and Alfred Louis Kroeber, who worked with Yurok informants in California, classified drift whales as a gathered resource, rather than a product of hunting, as those beneficiaries ran no risk.

It is harder to find evidence, archaeological or ethnographic, of North American indigenous people hunting large whales before cultural contact with Europeans, according to scholars of the Atlantic[25] and Pacific[20] coasts.

[27] When the early settlers arrived in New England, they saw from the deck of the Mayflower a huge number of whales, far more than they were accustomed to see in European waters, according to American historian W. Jeffrey Bolster.

[31] Wrapped in a thick blanket of blubber, the carcass retains its mammalian heat, and the process of decomposition takes place relatively quickly; once ashore, there is a risk of the swollen whale exploding.

In 2002, fourteen residents of a Bering Sea fishing village ate muktuk (skin and blubber) from a beluga whale which they "estimated had been dead for at least several weeks", resulting in eight of them developing botulism, with two of the affected requiring mechanical ventilation.

For example, William of Barkley Sound on Vancouver Island recounted tales to Edward Sapir, which were re-told by Kathryn Anne Bridge in a compendium about the Huu-ay-aht First Nations.

[36] R. Lee Lyman [de] proposed that drift whales might have formed a considerable summer food resource for people living on the coast of what is now Oregon, before contact with Europeans.