Spinophorosaurus

The anatomy, age, and location of specimens indicate that important developments in sauropod evolution may have occurred in North Africa, possibly controlled by climatic zones and plant biogeography.

An older succession of rocks, the Tiourarén Formation, was explored by American palaeontologist Paul Sereno, who conducted a large-scale excavation campaign in Niger between 1999 and 2003.

Sereno named new dinosaurs such as the sauropod Jobaria and the theropod Afrovenator from the Tiourarén; most finds were discovered along a cliff known as the Falaise de Tiguidit in the southern Agadez Region.

Sommer is the founder of CARGO, a relief organisation specialised in improving the local education system for the Tuareg people, while Joger is a biologist and the director of the State Natural History Museum, Braunschweig, Germany.

[2]: 17–27, 38 [1][4] Joger and Sommer then hired local Tuaregs for support and, after two days, had uncovered most of the specimen, which included a virtually complete, articulated vertebral column and several limb and pelvic bones.

In the autumn of 2006, Sommer and Joger, together with other associates of the Braunschweig museum, revisited the site in preparation for the excavation, putting one of the pelvic bones in plaster to test equipment and methodology.

On March 20, before the arrival of the trucks, the freshwater reserve of initially 200 L (53 US gal) was depleted as the local helpers had used it for washing the night before, causing members of the team to faint.

By contract with the Republic of the Niger, they were to be returned to the country in the future, managed by the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle in Niamey as well as by a smaller, newly built local museum.

[2]: 143 The future paratype specimen arrived in Germany on March 18, 2007; for its preparation, which took two and a half years, the Braunschweig museum rented a separate factory building.

[2]: 79–85 [10][11] The Spanish team produced separate 3D models from photographs of the holotype using photogrammetry (where photos are taken of an object from different angles to map them);[12] a caudal vertebra was put on display at the Elche museum in 2018.

[16][1][17][18] The holotype specimen consists of a braincase, a postorbital bone, a squamosal, a quadrate, a pterygoid, a surangular, and a nearly complete postcranial skeleton, which lacks the sternum, antebrachium, manus, and pes.

Elements preserved in this specimen but not the holotype include a premaxilla, maxilla, lacrimal, dentary, angular, the dorsal ribs of the right side, the humerus, and a pedal phalanx.

The basal tubera (a pair of extensions on the underside of the skull base that served as muscle attachments) were enlarged and were directed to the sides, unique among known sauropods.

[19] In these respects it was similar to mamenchisaurids from Asia but different from the genera Vulcanodon, Barapasaurus, and Patagosaurus from Gondwana (the southern supercontinent of the time), in which the upper end was only weakly broadened, and the rear flange lacking.

Of the ankle, the upper side of the astragalus had facets for articulation with the tibia and fibula that were not separated by a bony wall, and as many as eight nutrient foramina (openings that allow blood vessels to enter the bone).

Although found within the pelvic region, Remes and colleagues thought they were situated on the tip of the tail in the living animal, which they considered a distinguishing feature of the genus.

[1] In 2013, palaeontologists Emanuel Tschopp and Octávio Mateus reexamined the supposed tail spikes and found they did not have the typical rugose surface of osteoderms seen in other armoured dinosaurs, or the club-like expansion seen in Shunosaurus.

[29][19][30] The initial phylogenetic analysis presented by Remes and colleagues suggested Spinophorosaurus fell among the most basal sauropods known, being only slightly more derived than Vulcanodon, Cetiosaurus, and Tazoudasaurus.

[32] In a 2013 conference abstract, palaeontologist Pedro Mocho and colleagues re-evaluated the phylogenetic relationships of the genus by incorporating further information from newly prepared bones, arguing that Spinophorosaurus was nested within eusauropods.

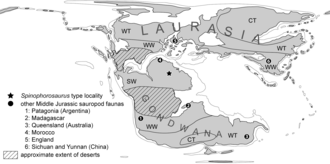

Remes and colleagues found that Spinophorosaurus shares features with Middle Jurassic East Asian sauropods (especially in the neck and tail vertebrae, scapula and humerus) but is very dissimilar from Lower and Middle Jurassic South American and Indian taxa (differences include the shape and development of vertebra features and shape of the scapula and humerus).

Remes and colleagues noted that more evidence was needed to support these interpretations but were confident that there was a connection between Jurassic sauropods of North Africa, Europe, and East Asia.

[1] Vidal and colleagues suggested in 2020 that the wedged sarcral vertebrae and upward deflecected vertebral column of Spinophorosaurus was an ancestral feature of eusauropods that could also be identified in more derived sauropods.

[23] Spinophorosaurus and some other sauropodomorphs did not have reduced vestibular apparatuses, a sensory system for balance and orientation in the inner ear, though this might have been expected in a lineage that led to heavy, plant-eating quadrupeds.

[2] In 2017, John Fronimos and Jeffrey Wilson used Spinophorosaurus as a model to study how the complexity of neurocentral sutures (the rigid joint connecting the neural arch of a vertebra to its centrum) in sauropods may have contributed to the strength of the spine.

In Spinophorosaurus, suture complexity was most pronounced in the front part of the trunk, indicating that stresses were highest in this region, probably because of the weight of the long neck and rib cage.

[37] In a 2018 conference abstract, Vidal used the virtual Spinophorosaurus skeleton to test hypothetical mating postures that have been proposed for sauropods that would involve a "cloacal kiss" (as is performed by most birds) rather than a male intromittent organ.

Vidal and colleagues demonstrated that both assumptions indeed hold true in modern giraffes, increasing confidence in range of motion estimates in extinct animals in general.

High browsing is also suggested by anatomical features, including the narrow snout, broad teeth, and proportionally long humerus compared to the scapula.

[15] Also in 2020, Vidal and colleagues added that the more vertical posture and greater upwards and downwards motion revealed by the digital model also supported high browsing abilities in Spinophorosaurus.

[39][40] Four theropod teeth were found closely associated with the Spinophorosaurus holotype (by a vertebra, pubis, and in the acetabulum); three had similarities with Megalosauridae and Allosauridae, while the fourth belongs to what may be one of the earliest known members of Spinosauridae.