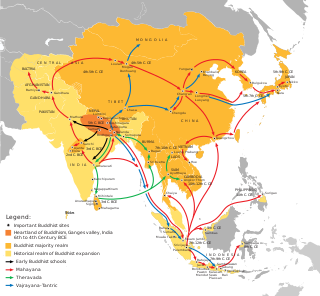

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

[5][6] The first documented translation efforts by Buddhist monks in China were in the 2nd century CE via the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory bordering the Tarim Basin under Kanishka.

From the 4th century onward, Chinese pilgrims like Faxian (395–414) and later Xuanzang (629–644) started to travel to northern India in order to get improved access to original scriptures.

[10] But from about this time, the Silk road trade of Buddhism began to decline with the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana (e.g. Battle of Talas), resulting in the Uyghur Khaganate by the 740s.

[14] In the middle of the 2nd century, the Kushan Empire under king Kaniṣka from its capital at Purushapura (modern Peshawar), India expanded into Central Asia.

Central Asian Buddhist missionaries became active shortly after in the Chinese capital cities of Loyang and sometimes Nanjing, where they particularly distinguished themselves by their translation work.

By the 8th century CE, the School of Esoteric Buddhism became prominent in China due to the careers of two South Asian monks, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra.

After the Battle of Talas of 751, Central Asian Buddhism went into serious decline[27] and eventually resulted in the extinction of the local Tocharian Buddhist culture in the Tarim Basin during the 8th century.

Central Asian missionary efforts along the Silk Road were accompanied by a flux of artistic influences, visible in the development of Serindian art from the 2nd to the 11th century CE in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang.

One story, first appearing in the (597 CE) Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶紀, concerns a group of Buddhist priests who arrived in 217 BCE at the capital of Qin Shi Huang in Xianyang (near Xi'an).

The monks, led by the shramana Shilifang 室李防, presented sutras to the First Emperor, who had them put in jail: But at night the prison was broken open by a Golden Man, sixteen feet high, who released them.

[30]The (668 CE) Fayuan Zhulin Buddhist encyclopedia elaborates this legend with Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great sending Shilifang to China.

The Book of the Later Han biography of Liu Ying, the King of Chu, gives the oldest reference to Buddhism in Chinese historical literature.

"[34] Huang-Lao or Huanglaozi 黄老子 is the deification of Laozi, and was associated with fangshi (方士) "technician; magician; alchemist" methods and xian (仙) "transcendent; immortal" techniques.

"[35]In 65 CE, Emperor Ming decreed that anyone suspected of capital crimes would be given an opportunity for redemption, and King Ying sent thirty rolls of silk.

The biography quotes Ming's edict praising his younger brother: The king of Chu recites the subtle words of Huanglao, and respectfully performs the gentle sacrifices to the Buddha.

Let (the silk which he sent for) redemption be sent back, in order thereby to contribute to the lavish entertainment of the upāsakas (yipusai 伊蒲塞) and śramaṇa (sangmen 桑門).

"[38] Second, Fan Ye's Book of Later Han quotes a "current" (5th-century) tradition that Emperor Ming prophetically dreamed about a "golden man" Buddha.

The overland route hypothesis, favored by Tang Yongtong, proposed that Buddhism disseminated eastward through Yuezhi and was originally practiced in western China, at the Han capital Luoyang where Emperor Ming established the White Horse Temple c. 68 CE.

The historian Rong Xinjiang reexamined the overland and maritime hypotheses through a multi-disciplinary review of recent discoveries and research, including the Gandhāran Buddhist Texts, and concluded: The view that Buddhism was transmitted to China by the sea route comparatively lacks convincing and supporting materials, and some arguments are not sufficiently rigorous [...] the most plausible theory is that Buddhism started from the Greater Yuezhi of northwest India and took the land roads to reach Han China.

After entering into China, Buddhism blended with early Daoism and Chinese traditional esoteric arts and its iconography received blind worship.

Although Ban Yong explained that they revere the Buddha, and neither kill nor fight, he has recording nothing about the excellent texts, virtuous Law, and meritorious teachings and guidance.

[40]In the Book of Later Han, "The Kingdom of Tianzhu" (天竺, Northwest India) section of "The Chronicle of the Western Regions" summarizes the origins of Buddhism in China.

The earliest version derives from the lost (mid-3rd century) Weilüe, quoted in Pei Songzhi's commentary to the (429 CE) Records of Three Kingdoms: "the student at the imperial academy Jing Lu 景盧 received from Yicun 伊存, the envoy of the king of the Great Yuezhi oral instruction in (a) Buddhist sutra(s).

"[43] Since Han histories do not mention Emperor Ai having contacts with the Yuezhi, scholars disagree whether this tradition "deserves serious consideration",[44] or can be "reliable material for historical research".

[45] Many sources recount the "pious legend" of Emperor Ming dreaming about Buddha, sending envoys to Yuezhi (on a date variously given as 60, 61, 64 or 68 CE), and their return (3 or 11 years later) with sacred texts and the first Buddhist missionaries, Kāśyapa Mātanga (Shemoteng 攝摩騰 or Jiashemoteng 迦葉摩騰) and Dharmaratna (Zhu Falan 竺法蘭).

[47] For example, the (late 3rd to early 5th-century) Mouzi Lihuolun says,[48] In olden days emperor Ming saw in a dream a god whose body had the brilliance of the sun and who flew before his palace; and he rejoiced exceedingly at this.

the scholar Fu Yi said: "Your subject has heard it said that in India there is somebody who has attained the Tao and who is called Buddha; he flies in the air, his body had the brilliance of the sun; this must be that god.

Huo defeated the people of prince Xiutu 休屠 (in modern-day Gansu) and "captured a golden (or gilded) man used by the King of Hsiu-t'u to worship Heaven.

[53] The (c. 6th century) A New Account of the Tales of the World claims this golden man was more than ten feet high, and Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE) sacrificed to it in the Ganquan 甘泉 palace, which "is how Buddhism gradually spread into (China).

However, these Buddhist monks did not only put an end to Japanese rule in 1945, but they also asserted their specific and separate religious identity by reforming their traditions and practices.