Square root

[7] A method for finding very good approximations to the square roots of 2 and 3 are given in the Baudhayana Sulba Sutra.

[9][10] [11] Aryabhata, in the Aryabhatiya (section 2.4), has given a method for finding the square root of numbers having many digits.

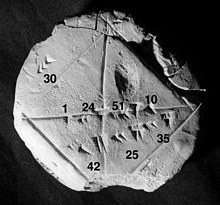

[12] The discovery of irrational numbers, including the particular case of the square root of 2, is widely associated with the Pythagorean school.

[13][14] Although some accounts attribute the discovery to Hippasus, the specific contributor remains uncertain due to the scarcity of primary sources and the secretive nature of the brotherhood.

Smith, Aryabhata's method for finding the square root was first introduced in Europe by Cataneo—in 1546.

According to Jeffrey A. Oaks, Arabs used the letter jīm/ĝīm (ج), the first letter of the word "جذر" (variously transliterated as jaḏr, jiḏr, ǧaḏr or ǧiḏr, "root"), placed in its initial form (ﺟ) over a number to indicate its square root.

Its usage goes as far as the end of the twelfth century in the works of the Moroccan mathematician Ibn al-Yasamin.

The square root of a nonnegative number is used in the definition of Euclidean norm (and distance), as well as in generalizations such as Hilbert spaces.

It defines an important concept of standard deviation used in probability theory and statistics.

Square roots frequently appear in mathematical formulas elsewhere, as well as in many physical laws.

The square roots of small integers are used in both the SHA-1 and SHA-2 hash function designs to provide nothing up my sleeve numbers.

A result from the study of irrational numbers as simple continued fractions was obtained by Joseph Louis Lagrange c. 1780.

Lagrange found that the representation of the square root of any non-square positive integer as a continued fraction is periodic.

In a sense these square roots are the very simplest irrational numbers, because they can be represented with a simple repeating pattern of integers.

Written in the more suggestive algebraic form, the simple continued fraction for the square root of 11, [3; 3, 6, 3, 6, ...], looks like this:

Pocket calculators typically implement efficient routines, such as the Newton's method (frequently with an initial guess of 1), to compute the square root of a positive real number.

[21][22] When computing square roots with logarithm tables or slide rules, one can exploit the identities

which is better for large n than for small n. If a is positive, the convergence is quadratic, which means that in approaching the limit, the number of correct digits roughly doubles in each next iteration.

This simplifies finding a start value for the iterative method that is close to the square root, for which a polynomial or piecewise-linear approximation can be used.

The time complexity for computing a square root with n digits of precision is equivalent to that of multiplying two n-digit numbers.

To find a definition for the square root that allows us to consistently choose a single value, called the principal value, we start by observing that any complex number

The principal square root function is thus defined using the non-positive real axis as a branch cut.

When the number is expressed using its real and imaginary parts, the following formula can be used for the principal square root:[28][29]

Because of the discontinuous nature of the square root function in the complex plane, the following laws are not true in general.

Unlike in an integral domain, a square root in an arbitrary (unital) ring need not be unique up to sign.

of integers modulo 8 (which is commutative, but has zero divisors), the element 1 has four distinct square roots: ±1 and ±3.

But the square shape is not necessary for it: if one of two similar planar Euclidean objects has the area a times greater than another, then the ratio of their linear sizes is

Let AHB be a line segment of length a + b with AH = a and HB = b. Construct the circle with AB as diameter and let C be one of the two intersections of the perpendicular chord at H with the circle and denote the length CH as h. Then, using Thales' theorem and, as in the proof of Pythagoras' theorem by similar triangles, triangle AHC is similar to triangle CHB (as indeed both are to triangle ACB, though we don't need that, but it is the essence of the proof of Pythagoras' theorem) so that AH:CH is as HC:HB, i.e. a/h = h/b, from which we conclude by cross-multiplication that h2 = ab, and finally that

(with equality if and only if a = b), which is the arithmetic–geometric mean inequality for two variables and, as noted above, is the basis of the Ancient Greek understanding of "Heron's method".

Constructing successive square roots in this manner yields the Spiral of Theodorus depicted above.