Cube root

and called the real cube root of x or simply the cube root of x in contexts where complex numbers are not considered.

In the case of negative real numbers, the largest real part is shared by the two nonreal cube roots, and the principal cube root is the one with positive imaginary part.

In an algebraically closed field of characteristic different from three, every nonzero element has exactly three cube roots, which can be obtained from any of them by multiplying it by either root of the polynomial

In an algebraically closed field of characteristic three, every element has exactly one cube root.

For example, in the quaternions, a real number has infinitely many cube roots.

Indeed, the cube function is increasing, so it does not give the same result for two different inputs, and covers all real numbers.

However this definition may be confusing when real numbers are considered as specific complex numbers, since, in this case the cube root is generally defined as the principal cube root, and the principal cube root of a negative real number is not real.

If x and y are allowed to be complex, then there are three solutions (if x is non-zero) and so x has three cube roots.

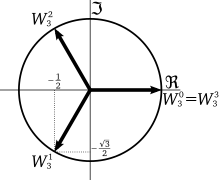

A real number has one real cube root and two further cube roots which form a complex conjugate pair.

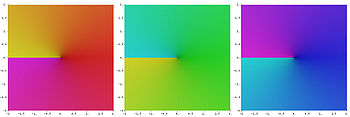

For complex numbers, the principal cube root is usually defined as the cube root that has the greatest real part, or, equivalently, the cube root whose argument has the least absolute value.

It is related to the principal value of the natural logarithm by the formula If we write x as where r is a non-negative real number and

lies in the range then the principal complex cube root is This means that in polar coordinates, we are taking the cube root of the radius and dividing the polar angle by three in order to define a cube root.

This difficulty can also be solved by considering the cube root as a multivalued function: if we write the original complex number x in three equivalent forms, namely The principal complex cube roots of these three forms are then respectively Unless x = 0, these three complex numbers are distinct, even though the three representations of x were equivalent.

This is related with the concept of monodromy: if one follows by continuity the function cube root along a closed path around zero, after a turn the value of the cube root is multiplied (or divided) by

In 1837 Pierre Wantzel proved that neither of these can be done with a compass-and-straightedge construction.

For real floating-point numbers this method reduces to the following iterative algorithm to produce successively better approximations of the cube root of a: The method is simply averaging three factors chosen such that at each iteration.

Each iteration of Newton's method costs two multiplications, one addition and one division, assuming that 1/3a is precomputed, so three iterations plus the precomputation require seven multiplications, three additions, and three divisions.

Each iteration of Halley's method requires three multiplications, three additions, and one division,[1] so two iterations cost six multiplications, six additions, and two divisions.

Thus, Halley's method has the potential to be faster if one division is more expensive than three additions.

With either method a poor initial approximation of x0 can give very poor algorithm performance, and coming up with a good initial approximation is somewhat of a black art.

Some implementations manipulate the exponent bits of the floating-point number; i.e. they arrive at an initial approximation by dividing the exponent by 3.

[1] Also useful is this generalized continued fraction, based on the nth root method: If x is a good first approximation to the cube root of a and

Cubic equations, which are polynomial equations of the third degree (meaning the highest power of the unknown is 3) can always be solved for their three solutions in terms of cube roots and square roots (although simpler expressions only in terms of square roots exist for all three solutions, if at least one of them is a rational number).

If two of the solutions are complex numbers, then all three solution expressions involve the real cube root of a real number, while if all three solutions are real numbers then they may be expressed in terms of the complex cube root of a complex number.

The calculation of cube roots can be traced back to Babylonian mathematicians from as early as 1800 BCE.

[2] In the fourth century BCE Plato posed the problem of doubling the cube, which required a compass-and-straightedge construction of the edge of a cube with twice the volume of a given cube; this required the construction, now known to be impossible, of the length

A method for extracting cube roots appears in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, a Chinese mathematical text compiled around the second century BCE and commented on by Liu Hui in the third century CE.

[3] The Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria devised a method for calculating cube roots in the first century CE.

His formula is again mentioned by Eutokios in a commentary on Archimedes.

[4] In 499 CE Aryabhata, a mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy, gave a method for finding the cube root of numbers having many digits in the Aryabhatiya (section 2.5).