Squares of Savannah, Georgia

Although cherished by many today for their aesthetic beauty, the first squares were originally intended to provide colonists space for practical reasons such as militia training exercises.

(Two points on this grid were occupied by Colonial Park Cemetery, established in 1750, and four others—in the southern corners of the downtown area—were never developed with squares.)

[5] This arrangement is illustrated in the 1770 Plan of Savannah, reproduced here, and remains readily visible in the modern aerial photograph above.

[8] The five squares along Bull Street—Monterey, Madison, Chippewa, Wright, and Johnson—were intended to be grand monument spaces and have been called Savannah's "Crown Jewels."

[7] The first four squares were laid out by James Oglethorpe in 1733, the same year in which he founded the Georgia colony and the city of Savannah.

The ward and square were named for Sir Matthew Decker, one of Trustees for the Establishment of the Colony of Georgia in America, Commissioner of funds collection for the Trust, director and governor of the East India Company, and member of Parliament.

[13] A bronze statue, by Susie Chisholm, of songwriter-lyricist Johnny Mercer, a native Savannahian, was formally unveiled in Ellis Square on November 18, 2009.

[14] St. James Square was named in honor of a green space in London, England, and marked one of the most fashionable neighborhoods in early Savannah.

The square also contains tributes to the Girl Scouts of the USA, founded by Savannahian Juliette Gordon Low, and to the chambered nautilus.

Wesley spent most of his life in England but undertook a mission to Savannah (1735–1738), during which time he founded the first Sunday school in America.

[3] Reynolds Square was the site of the Filature,[16] which housed silkworms as part of an early—and unsuccessful—attempt to establish a silk industry in the Georgia colony.

Immediately to its south, across East Saint Julian Street and in the southwestern trust lot, is the Oliver Sturges House.

The residences of the Royal Surveyors of Georgia and South Carolina were located on the northeastern trust lots, the site of today's Owens–Thomas House.

The square contains a pedestal honoring Moravian missionaries who arrived at the same time as John Wesley and settled in Savannah from 1735 to 1740, before resettling in Pennsylvania.

Savannah grew rapidly in the late 18th century and six new wards were established in the 1790s alone, including the four that now comprise the northeastern quadrant of the Historic District.

[20] In 1964 Savannah Landscape Architect Clermont Huger Lee and Mills B Lane planned and initiated a project to close the fire lane, add North Carolina bluestone pavers, initiate the use of different paving materials, install water cisterns, and lastly install new walks, benches, lighting, and plantings.

It is located on the western end of town at the intersection of Montgomery Street and W Julian Street, bordered on the north side by W Bryan St and on the south side by W Congress St.[22] It was named in 1791 for Benjamin Franklin, who served as an agent for the colony of Georgia from 1768 to 1778 and who had died in 1790.

[22][24] The memorial sculpture includes a depiction of 12-year-old Henri Christophe, who became the commander of the Haitian army and King of Haiti.

In 1963 Savannah Landscape Architect Clermont Huger Lee and Mills B Lane planned and initiated a project to replace the sand square with plantings, add walks, benches, lighting and plantings, and install barriers to prevent drive through for fire lane.

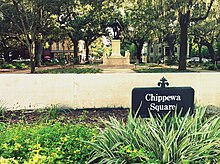

[5] Chippewa Square was laid out in 1815 and named in honor of American soldiers killed in the Battle of Chippawa during the War of 1812.

In the center of the square is the James Oglethorpe Monument, created by sculptor Daniel Chester French and architect Henry Bacon and unveiled in 1910.

[18] Busts of Confederate figures Francis Stebbins Bartow and Lafayette McLaws were moved from Chippewa Square to Forsyth Park to make room for the Oglethorpe monument.

[10] Orleans Square is located on Barnard, between Hull and Perry Streets, and is adjacent to the Savannah Civic Center.

Given this proximity, Lafayette Square features prominently in Savannah's massive Saint Patrick's Day celebrations.

[9] Prior to the birth of the historical preservation movement and the restoration of much of Savannah's downtown Pulaski sheltered a sizeable homeless population and was one of several squares that had been paved to allow traffic to drive straight through its center.

[15] A large iron armillary sphere stands in the center of the square, supported by six small metal turtles.

In 1969 Savannah Landscape Architect Clermont Huger Lee and Mills B Lane planned and initiated a project to remove the central vandalized playground, close the fire lane, install an armillary sundial, and add new walls, benches, lighting, and plantings.

In 2004 a skull was found by utility workers outside the Massie Heritage Interpretation Center on the square's southeastern side.

[29] After 1851, as the city expanded south of Gaston Street, further extensions of Oglethorpe's grid of wards and squares were abandoned.

While some authorities believe that the original plan allowed for growth of the city and thus expansion of the grid, the regional plan suggests otherwise: the ratio of town lots to country lots was in balance and growth of the urban grid would have destroyed that balance.