Squatting

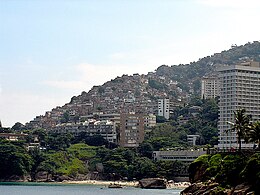

Informal settlements in Latin America are known by names such as villa miseria (Argentina), pueblos jóvenes (Peru) and asentamientos irregulares (Guatemala, Uruguay).

"[12] Others have a different view; UK police official Sue Williams, for example, has stated that "Squatting is linked to anti-social behaviour and can cause a great deal of nuisance and distress to local residents.

[41] In October 2018, Fatou Bensouda, the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court stated that Israel's planned demolition of Bedouin village Khan al-Ahmar could constitute a war crime.

[45][46] A place was occupied in Beşiktaş district of Istanbul on March 18, 2014, and named Berkin Elvan Student House, after a 15-year-old boy who was shot during the Gezi protests and later died.

[51] In Thailand, although evictions have reduced their visibility or numbers in urban areas, many squatters still occupy land near railroad tracks, under overpasses, and waterways.

Commercial squatting is common in Thailand, where businesses temporarily seize nearby public real estate (such as sidewalks, roadsides, beaches, etc.)

[60] After World War II many people were left homeless in the Philippines and they built makeshift houses called "barong-barong" on abandoned private land.

[76] In the early 1990s, the Government of Moscow prepared to renovate buildings, but then ran out of money, meaning that squatters occupied prime real estate.

[81] Starting from December 2012, Greek Police initiated extensive raids in a number of squats in Athens, arresting and charging with offences all illegal occupants (mostly anarchists).

[95][96] In early twentieth century France, several artists who would later become world-famous, such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Amedeo Modigliani and Pablo Picasso squatted at the Bateau-Lavoir, in Montmartre, Paris.

[99] The RHINO (Retour des Habitants dans les Immeubles Non-Occupés, in English: Return of Inhabitants to Non-Occupied Buildings) was a 19-year-long squat in Geneva.

[100] During the public opposition in the 1970s, squatting in West German cities led to what Margit Mayer [de] termed "a self-confident urban counterculture with its own infrastructure of newspapers, self-managed collectives and housing cooperatives, feminist groups, and so on, which was prepared to intervene in local and broader politics".

The space, which had hosted lectures and also Iceland's trade union and anarchist libraries, was moved to another location but the occupiers were unhappy that the new use of the building would be a guest house for tourists.

[119] There are many left-wing self-organised occupied projects across Italy such as Cascina Torchiera and Centro Sociale Leoncavallo in Milan and Forte Prenestino in Rome.

In contrast with the dominant jurisprudence, new case-law (from the Rome Tribunal and the Supreme Court of Cassation) instructs the government to pay damages in case of squatting if the institutions have failed to prevent it.

[7] Notable squats in cities around the country include ACU and Moira in Utrecht, the Poortgebouw in Rotterdam, OCCII, OT301 and Vrankrijk in Amsterdam, the Grote Broek in Nijmegen, Vrijplaats Koppenhinksteeg in Leiden, De Vloek in The Hague and the Landbouwbelang in Maastricht.

The number of squatted social centres in Barcelona grew from under thirty in the 1990s to around sixty in 2014, as recorded by Info Usurpa (a weekly activist agenda).

[127] Social centres exist in cities across the country, for example Can Masdeu and Can Vies in Barcelona and Eskalera Karakola and La Ingobernable in Madrid.

[149] The high number of businesses failing in urban Wales has led to squatting becoming a growing issue in large cities like Swansea and Cardiff.

[171] In 2002, the New York City administration agreed to work with eleven squatted buildings on the Lower East Side in a deal brokered by the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board with the condition the apartments would eventually be turned over to the tenants as low-income housing cooperatives.

[172] In Latin American and Caribbean countries, informal settlements result from internal migration to urban areas, lack of affordable housing and ineffective governance.

[18]: 42 Nevertheless, forced by hunger and unemployment to take action, 20,000 squatters occupied 211 hectares of disused privately owned land on the periphery of Buenos Aires in 1981, forming six new settlements.

[18]: 13–15 More recently, governments have switched from a policy of eradication to one of giving squatters title to their lands, as part of various programs to move people out of slums and to alleviate poverty.

[176] Former squatters found that it was hard to maintain the property title over time after deaths or divorces and that banks changed their loan requirements so as to exclude them.

[173] In Guayaquil, Ecuador's largest city and main port, around 600,000 people in the early 1980s were either squatting on self-built structures over swamplands or living in inner-city slums.

[18]: 25, 76 Illegal settlements frequently resulted from land invasions, in which large groups of squatters would build structures and hope to prevent eviction through strength in numbers.

[187] The squats are mostly inhabited by the poorest strata of society, and usually lack much infrastructure and public services, but in some cases, already have reached the structure needed for a city.

[193] This was the result of an extended civil conflict between rebels, paramilitaries, cocaine traders and the state, which left 40% of rural land without legal title.

During the late 1940s the squatting of hundreds of empty houses and military camps, forced federal and state governments to provide emergency shelter during a period when Australians faced a shortage of more than 300 000 homes.

The Midnight Star squat was used as a self-managed social centre in a former cinema, before being evicted after being used as a convergence space during the 2002 World Trade Organization meeting.