Saint Basil's Cathedral

Nothing similar can be found in the entire millennium of Byzantine tradition from the fifth to the fifteenth century ... a strangeness that astonishes by its unexpectedness, complexity and dazzling interleaving of the manifold details of its design.

[20][21][22] Many historians are convinced that it is a myth, as the architect later participated in the construction of the Cathedral of the Annunciation in Moscow as well as in building the walls and towers of the Kazan Kremlin.

[31][32] The formerly open ground-floor arcades were filled with brick walls; the new space housed altars from thirteen former wooden churches erected on the site of Ivan's executions in Red Square.

[5] Wooden shelters above the first-floor platform and stairs (the cause of frequent fires) were rebuilt in brick, creating the present-day wrap-around galleries with tented roofs above the porches and vestibules.

[5] The tall single tented roof of this belltower, built in the vernacular style of the reign of Alexis I, significantly changed the appearance of the cathedral, adding a strong asymmetrical counterweight to the church itself.

The church did not have a congregation of its own and could only rely on donations raised through public campaigning;[45] national authorities in Saint Petersburg and local in Moscow prevented financing from state and municipal budgets.

[45] In 1899 Nicholas II reluctantly admitted that this expense was necessary,[46] but again all the involved state and municipal offices, including the Holy Synod, denied financing.

[50] During World War I, the church was headed by protoiereus Ioann Vostorgov, a nationalist preacher and a leader of the Black-Hundredist Union of the Russian People.

[52] In the first half of the 1930s, the church became an obstacle for Joseph Stalin's urbanist plans, carried out by Moscow party boss Lazar Kaganovich, "the moving spirit behind the reconstruction of the capital".

In particular, a frequently-told story is that Kaganovich picked up a model of the church in the process of envisioning Red Square without it, and Stalin sharply responded "Lazar, put it back!"

In the first years after World War II, renovators restored the historical ground-floor arcades and pillars that supported the first-floor platform, cleared up vaulted and caissoned ceilings in the galleries, and removed "unhistoric" 19th-century oil paint murals inside the churches.

[70] A large group of Italian architects and craftsmen continuously worked in Moscow in 1474–1539, as well as Greek refugees who arrived in the city after the fall of Constantinople.

[71] These two groups, according to Shvidkovsky, helped Moscow rulers in forging the doctrine of Third Rome, which in turn promoted assimilation of contemporary Greek and Italian culture.

[71] Shvidkovsky noted the resemblance of the cathedral's floorplan to Italian concepts by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Donato Bramante, but most likely Filarete's Trattato di architettura.

[72] Nikolay Brunov recognized the influence of these prototypes but not their significance;[73] he suggested that mid-16th century Moscow already had local architects trained in Italian tradition, architectural drawing and perspective, and that this culture was lost during the Time of Troubles.

As a result of this subtle calculated[80] asymmetry, viewing from the north and the south presents a complex multi-axial shape, while the western façade, facing the Kremlin, appears properly symmetrical and monolithic.

[88] Restorers who replaced parts of the brickwork in 1954–1955 discovered that the massive brick walls conceal an internal wooden frame running the entire height of the church.

[5][89] This frame, made of elaborately tied thin studs, was erected as a life-size spatial model of the future cathedral and was then gradually enclosed in solid masonry.

The 25 seats from the biblical reference are alluded to in the building's structure, with the addition of eight small onion domes around the central tent, four around the western side church and four elsewhere.

[94] The walls of the church mixed bare red brickwork or painted imitation of bricks with white ornaments, in roughly equal proportion.

According to the legend, its "missing" ninth church (more precisely a sanctuary) was "miraculously found" during a ceremony attended by Tsar Ivan IV, Metropolitan Makarius with the divine intervention of Saint Tikhon.

Piskaryov's Chronist wrote in the second quarter of the 17th century: And the Tsar came to the dedication of the said church with Tsaritsa Nastasia and with Metropolitan Makarius and brought the icon of St Nicholas the Wonderworker that came from Vyatka.

And the Tsar ordered it to be dedicated to Nicholas ... Construction of wrap-around ground-floor arcades in the 1680s visually united the nine churches of the original cathedral into a single building.

[5] The abstract allegory was reinforced by real-life religious rituals where the church played the role of the biblical Temple in Jerusalem: The capital city, Moscow, is split into three parts; the first of them, called Kitai-gorod, is encircled with a solid thick wall.

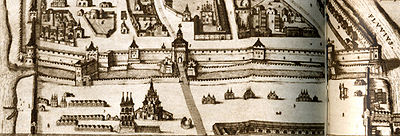

Here is, also, the main muscovite marketplace: the trading square is built as a brick rectangle, with twenty lanes on each side where the merchants have their shops and cellars ... Templum S. Trinitatis, etiam Hierusalem dicitur; ad quo Palmarum fest Patriarcha asino insidens a Caesare introducitur.Temple of Holy Trinity, also called Jerusalem, to where the tsar leads the Patriarch, sitting on a donkey, on the Palm Holiday.

[115] Mikhail Petrovich Kudryavtsev [ru] noted that all cross processions of the period began, as described by Petreius, from the Dormition Church, passed through St. Frol's (Saviour's) Gate and ended at Trinity Cathedral.

[119] According to Mokeev, medieval Moscow, constrained by the natural boundaries of the Moskva and Neglinnaya Rivers, grew primarily in a north-easterly direction into the posad of Kitai-gorod and beyond.

The main road connecting the Kremlin to Kitai-gorod passed through St. Frol's (Saviour's) Gate and immediately afterwards fanned out into at least two radial streets (present-day Ilyinka and Varvarka), forming the central market square.

[122] Tsar Ivan's decision to build the church next to St. Frol's Gate established the dominance of the eastern hub with a major vertical accent,[122] and inserted a pivot point between the nearly equal Kremlin and Kitai-gorod into the once amorphous marketplace.

[32] Conrad Bussow, describing the triumph of False Dmitriy I, wrote that on 3 June 1606 "a few thousand men hastily assembled and followed the boyarin with [the impostor's] letter through the whole Moscow to the main church they call Jerusalem that stands right next to the Kremlin gates, raised him on Lobnoye Mesto, called out for the Muscovites, read the letter and listened to the boyarin's oral explanation.