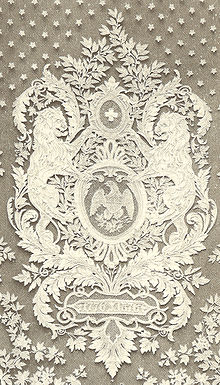

St. Gallen embroidery

With the advent of the First World War, the demand for the luxury dropped suddenly and significantly and so a lot of people were unemployed, which resulted in the biggest economic crisis in the region.

Nevertheless, the St. Galler Spitzen (as the embroidery is also called) are still very popular as a raw material for expensive haute couture creations in Paris and count among the most famous textiles in the world.

The General-Societät der englischen Baumwollspinnerei in St. Gallen, the first Swiss stock company founded in 1801, had to close in 1817 due to lack of money.

However, Mange allowed the Maschinen-Werkstätte und Eisengießerey, that Michael Weniger had recently opened in St. Georgen (city district of St. Gallen), the production of such machines.

The simultaneous invention of the sewing machine could, however, fix the problem, because now even smaller pieces could be sewn in great numbers on towels.

The meteoric rise of St. Gallen embroidery can only be explained by a combination of economic, political, and technical conditions in the second half of the 19th century.

Thus, embroidery had soon become in large part homework and a major addition to the income of the peasants and craftsmen, mainly in winter, as it had partially been before in the linen or spinning time.

Particularly benefiting from the development of home embroidery were the traders, who imported the commondies for the embroiders and distributed the finished products back around the world.

Representatives of trading companies from overseas visited St. Gallen regularly to select patterns and to place new orders.

They built a duty-free storehouse in the city and opened a school for pattern designers; they also started today's Textile Museum.

Only around 1898 did the embroidery industry recover through various internal reforms, restrictions on maximum working hours and minimum wages, and the rise of the global economy.

The last crucial step in the technical development of embroidery, the invention of the so-called automatic machines, in which the design is no longer entered using the pantographs but by punched card.

In 1911, Arnold Groebli, the son of Isaac, improved the machine at Saurer (in Arbon) so that they were in almost all respects superior to the German ones.

The Schiffli- and hand embroidery machines were not removed completely, despite the now much higher speed, because the preparation of punched cards was often not worth the effort for small jobs.

The last little flurry of exports came in 1919 after the end of the war, when the reconstruction of the war-stricken countries brought another short rise.

In 1937, however, exports rose again for the first time to over 20 million Swiss francs, and the majority of the 97 newly opened facilities in the area were in the textile industry.

The workday lasted 10–14 hours, which caused health damage because of straining of the muscles-most embroidery machines were still operated by hand-and anemia or pulmonary tuberculosis.

Moreover, the position of the embroiderers in front of the pantographs was, from an ergonomic point of view, extremely bad-the chest was severely compressed in its development and the spine was crooked.

Various doctors tried to counteract this problem with studies and public education in the areas of health, nutrition counseling, and child care-with measurable success.

The Art Nouveau and Neu-Renaissance buildings constructed from 1880 to 1930 define the image of the commercial districts built around the old city.

The names of these former business places suggest the past significance of world trade for the city: Pacific, Oceanic, Atlantic, Chicago, Britannia, Washington, Florida, and so forth.