St Giles in the Fields

The first recorded church on the site was a chapel of the Parish of Holborn attached to a monastery and leper hospital founded by Matilda of Scotland, "Good Queen Maud", consort of Henry I between the years 1101 and 1109.

As George Walter Thornbury noted in London Old & New "it is remarkable that in almost every ancient town in England, the church of St. Giles stands either outside the walls, or, at all events, near its outlying parts, in allusion, doubtless, to the arrangements of the Israelites of old, who placed their lepers outside the camp.

[4] The 14th century was turbulent for the hospital, with frequent accusations of corruption and mismanagement from the City and Crown authorities and suggestions that members of the Order of Saint Lazarus (known as Lazar brothers) put the affairs of the monastery ahead of caring for the lepers.

This was opposed by the Lazars and their new Master, Walter Lynton, who responded by leading a group of armed men to St Giles, recapturing it by force[11] and by the City of London, which withheld rent money in protest.

123 feet long and the breadth 57 wide with a steeple in rubbed brick, galleries adorning the north and south aisles with a great east window of coloured and painted glass.

This provoked the Protestant (particularly Puritan) parishioners of St Giles to present Parliament with a petition listing and enumerating the 'popish reliques' with which Heywood had set up 'at needless expense to the parish'[13] as well as the 'Superstitious and Idolatrous manner of administration of the Sacrament of the Lords Supper'.

William Heywood was reinstated to his living at St Giles for a short period before being succeeded by the Dr Robert Boreman, previously Clerk of the Green Cloth to Charles I and a fellow deprived Royalist.

Sharp's father had been a prominent Bradfordian puritan who enjoyed the favour of Thomas Fairfax and inculcated him in Calvinist, Low Church, doctrines, while his mother, being strong Royalist, instructed him in the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer.

He preached regularly (at least twice every Sunday at St Giles as well as weekly in other city churches) and with "much fluency, piety [and] gravity", becoming, according to Bishop Burnet "one of the most popular preachers of the age".

[26] In 1685 Sharp was tasked by the Lord Mayor with drawing up for the Grand Jury of London their address of congratulations on the accession of James II and on 20 April 1686 he became chaplain in ordinary to the King.

However, provoked by the subversion of his parishioners' faith by Jesuit priests and Jacobite agents, Sharp preached two sermons at St. Giles on 2 and 9 May, which were held to reflect adversely on the King's religious policy.

As the population grew, so did their dead, and eventually there was no room in the graveyard: many burials of parishioners (including the architect Sir John Soane) in the 18th and 19th centuries took place outside the parish in the churchyard of St Pancras old church John Wesley, the English cleric, theologian, and evangelist and leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism is believed to have preached occasionally at Evening Prayer at St Giles from the large pulpit dating from 1676 which survived the rebuild and, indeed, is still in use today.

[3] Although St Giles escaped direct bombing hits in the Second World War, high explosives still destroyed most of its Victorian stained glass and the roof of the nave was severely damaged.

It adhered closely to Flitcroft's original intentions, on which the Georgian Group and Royal Fine Art Commission were consulted[40] The resulting works were praised by the journalist and poet John Betjeman as "one of the most successful post-war church restorations" (Spectator 9 March 1956).

He also worked successfully with Austen Williams of St Martin-in-the-Fields to defeat the comprehensive redevelopment of Covent Garden, stopping the construction of a major road planned to run through the parish, which would have involved the demolition of the Almshouses and the destruction of this historic quarter of London, personally giving evidence before the public inquiry.

Taylor eventually came to see himself and St Giles as defenders and custodians of the traditions of the Church of England, the Established Liturgy and the use of the Book of Common Prayer which he maintained in the Parish with the support of the PCC.

of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster has described the place thus: The churchyard of St Giles may appear to the casual passer-by as a convenient green space to sit down, enjoy a sandwich and catch up with the social media.

In actual fact it is one of London's most hallowed spots, with the remains of eleven beatified martyrs hidden beneath the ground, silently witnessing to the faith and awaiting the day of resurrection.

The inscription on the side of the tomb is still faintly visible and reads: Here lieth Richard Pendrell, Preserver and Conductor to his sacred Majesty King Charles the Second of Great Britain, after his Escape from Worcester Fight, in the Year 1651, who died Feb. 8, 1671.

The carving is probably the work of a wood-carver named Mr Love and was commissioned in 1686 when directions were given by the vestry to erect "a substantial gate out of the wall of the churchyard near the round house".

[52] The Gate was rebuilt in 1810 to the designs of the architect and churchwarden of St Giles William Leverton[53] and, In 1865, being unsafe, it was taken down and carefully re-erected opposite the west door in anticipation of the re-routing of Charing Cross Road.

[22] Edward, brother of the Christian poet George Herbert published his controversial metaphysical treatise De Veritate in 1624 on the advice of the philosopher Hugo Grotius (it remains on the Catholic index of forbidden books).

James Shirley and Thomas Nabbes both writers of masques, city comedies and historical tragedies enjoyed a long connection with the church and parish and both are buried within the churchyard.

He was known in his day for his comedies of fashionable London life in the 1630s but is perhaps best known today for his poem 'Death the Leveller' taken from his Contention of Ajax and Ulysses which begins: The glories of our blood and state Are shadows, not substantial things; There is no armour against fate; Death lays his icy hand on kings: Sceptre and crown Must tumble down, And in the dust be equal made With the poor crooked scythe and spade.

This period, which coincided with the Popish Plot, reached its grisly degringolade in the trial and execution of 12 Jesuits and the Roman Catholic Bishop of Armagh, Oliver Plunkett who were all buried in St Giles Churchyard not far from both Marvell and Belasyse.

Despite his own achievements as a translator and fabulist, Sir Roger is perhaps most often remembered for attempting to suppress the following lines from Book I of Milton's Paradise Lost, for potentially impugning the King's majesty: As when the Sun new ris'n Looks through the Horizontal misty Air Shorn of his Beams, or from behind the Moon In dim Eclips disastrous twilight sheds On half the Nations, and with fear of change Perplexes Monarchs Although he has been viewed unsympathetically by posterity for his perceived bigotry and anti-republican paranoia he was, at least in his own eyes, vindicated by the discovery and foiling of the Rye House Plot in 1683.

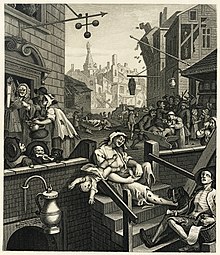

[68] Walter Thornbury later remarked in London Old and New that "there is scarcely an execution at "Tyburn Tree," recorded in the "Newgate Calendar," in which the fact is not mentioned that the culprit called at a public-house en route for a parting draught".

[5] The "public house" mentioned appears to have been on the current site of the Angel (it is confusingly named The Crown in many ballads and stories) now owned by Samuel Smith's brewery of Tadcaster.

[73] The Victorian historical novelist William Harrison Ainsworth composed a ballad and drinking song on the history of the St Giles Cup beginning: Where Saint Giles's Church stands, once a lazar-house stood; And chained to its gates was a vessel of wood; A broad-bottomed bowl, from which all the fine fellows, Who passed by that spot on their way to the gallows, Might tipple strong beer Their spirits to cheer, And drown in a sea of good liquor all fear!

With the abatement of leprosy in England by the mid 16th century the Hospital of St Giles had begun to admit the indigent and the destitute and the sight of homeless in the parish and within the churchyard has been familiar from at least that time.