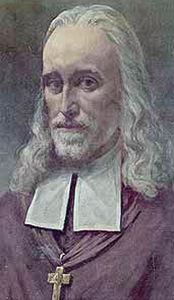

Oliver Plunkett

[3] Throughout the period of the Commonwealth and the first years of Charles II's reign, he successfully pleaded the cause of the Irish Catholic Church, and also served as theological professor at the College of Propaganda Fide.

On the enactment of the Stuart Restoration penal laws known as the Test Act in 1673, to which Plunkett would not agree for doctrinal reasons, the college was closed and demolished.

The moving spirit behind the campaign is said to have been Arthur Capell, the first Earl of Essex, who had been Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1672-77 and hoped to resume the office by discrediting the Duke of Ormonde.

At some point before his final incarceration, he took refuge in a church that once stood in the townland of Killartry, in the parish of Clogherhead in County Louth, seven miles outside Drogheda.

Plunkett was tried at Dundalk for conspiring against the state by allegedly plotting to bring 20,000 French soldiers into the country, and for levying a tax on his clergy to support 70,000 men for rebellion.

Though this was unproven, some in government circles were worried about the possibility that a repetition of the Irish rebellion of 1641 was being planned and in any case, this was a convenient excuse for proceeding against Plunkett.

In private however, he made clear his belief in Plunkett's innocence and his contempt for the informers against him: "silly drunken vagabonds... whom no schoolboy would trust to rob an orchard".

[6] Plunkett did not object to facing an all-Protestant jury, but the trial soon collapsed as the prosecution witnesses were themselves wanted men and afraid to turn up in court.

The second trial has generally been regarded as a serious miscarriage of justice; Plunkett was denied defending counsel (although Hugh Reily acted as his legal advisor) and time to assemble his defence witnesses, and he was also frustrated in his attempts to obtain the criminal records of those who were to give evidence against him.

[8] The Scottish clergyman and future Bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet, an eyewitness to the Plot trials, had no doubt of the innocence of Plunkett, whom he praised as a wise and sober man who wished only to live peacefully and tend to his congregation.

More recently the High Court judge Sir James Comyn called it a grave mistake: while Plunkett, by virtue of his office, was clearly guilty of "promoting the Catholic faith", and may possibly have had some dealings with the French, there was never the slightest evidence that he had conspired against the King's life.

[11] The jury returned within fifteen minutes with a guilty verdict and Archbishop Plunkett replied: "Deo Gratias" (Latin for "Thanks be to God").

Numerous pleas for mercy were made but Charles II, although himself a reputed crypto-Catholic,[12] thought it too politically dangerous to spare Plunkett.

[13] Lord Essex, apparently realising too late that his intrigues had led to the condemnation of an innocent man, made a similar plea for mercy.

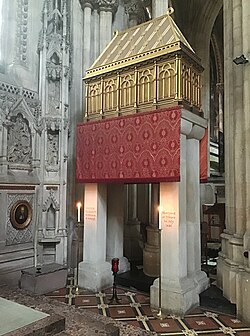

[13] His body was initially buried in two tin boxes, next to five Jesuits who had died previously, in the courtyard of St Giles in the Fields church.

Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich, twenty enrobed bishops and a number of abbots mounted a stage beneath a scaffolding shelter on 1 July 1981.