Stab-in-the-back myth

[2] Historians inside and outside of Germany, whilst recognising that economic and morale collapse on the home front was a factor in German defeat, unanimously reject the myth.

In order to implement the Act, however, Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg and his Chief-of-Staff, First Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff had to make significant concessions to labour unions and the Reichstag.

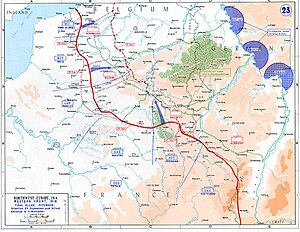

Contributing to the Dolchstoßlegende, the overall failure of the German offensive was blamed on strikes in the arms industry at a critical moment, leaving soldiers without an adequate supply of materiel.

[11] After the last German offensive on the Western Front failed in 1918, Hindenburg and Ludendorff admitted that the war effort was doomed, and they pressed Kaiser Wilhelm II for an armistice to be negotiated, and for a rapid change to a civilian government in Germany.

[13][b]In this way, Ludendorff was setting up the republican politicians – many of them Socialists – who would be brought into the government, and would become the parties that negotiated the armistice with the Allies, as the scapegoats to take the blame for losing the war, instead of himself and Hindenburg.

[16] On 5 October, the German Chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden, contacted U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, indicating that Germany was willing to accept his Fourteen Points as a basis for discussions.

[17] On 26 October, Ludendorff was dismissed from his post by the Emperor and replaced by Lieutenant General Wilhelm Groener, who started to prepare the withdrawal and demobilisation of the army.

[18] On 11 November 1918, the representatives of the newly formed Weimar Republic – created after the Revolution of 1918–1919 forced the abdication of the Kaiser – signed the armistice that ended hostilities.

In his autobiography, Ludendorff's successor Groener stated, "It suited me just fine when the army and the Supreme Command remained as guiltless as possible in these wretched truce negotiations, from which nothing good could be expected".

[12] Thus the conditions were set for the "stab-in-the-back myth", in which Hindenburg and Ludendorff were held to be blameless, the German Army was seen as undefeated on the battlefield, and the republican politicians – especially the Socialists – were accused of betraying Germany.

Further blame was laid at their feet after they signed the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which led to territorial losses and serious financial pain for the shaky new republic, including a crippling schedule of reparation payments.

These November Criminals, or those who seemed to benefit from the newly formed Weimar Republic, were seen to have "stabbed them in the back" on the home front, by either criticising German nationalism, instigating unrest and mounting strikes in the critical military industries, or by profiteering.

When consulted on terms for an armistice in October 1918, Douglas Haig, commander of the British and Commonwealth forces on the western front, stated that "Germany is not broken in the military sense.

[21]: 316 A report from the retired German general Montgelas, who had previously contacted British intelligence to discuss peace overtures, stated that "The military situation is desperate, if not hopeless, but it is nothing compared to the interior condition due to the rapid spread of Bolshevism.".

On 27th October Emperor Karl threw up the sponge [...] Germany lay practically open to invasion through Bohemia and Tyrol into Silesia, Saxony, and Bavaria.

[24] According to historian Richard Steigmann-Gall, the stab-in-the-back concept can be traced back to a sermon preached on 3 February 1918, by Protestant Court Chaplain Bruno Doehring, nine months before the war had ended.

[29] Right-wing groups used it as a form of attack against the early Weimar Republic government, led by the Social Democratic Party (SPD), which had come to power with the abdication of the Kaiser.

However, even the SPD had a part in furthering the myth when Reichspräsident Friedrich Ebert, the party leader, told troops returning to Berlin on 10 November 1918 that "No enemy has vanquished you," (kein Feind hat euch überwunden!

[31]Hindenburg, Chief of the German General Staff at the time of the Ludendorff Offensive, also mentioned this event in a statement explaining the Kaiser's abdication:The conclusion of the armistice was directly impending.

[4] Charges of a Jewish conspiratorial element in Germany's defeat drew heavily upon figures such as Kurt Eisner, a Berlin-born German Jew who lived in Munich.

The Weimar Republic under Friedrich Ebert violently suppressed workers' uprisings with the help of Gustav Noske and Reichswehr general Wilhelm Groener, and tolerated the paramilitary Freikorps forming all across Germany.

Many of its representatives such as Matthias Erzberger and Walther Rathenau were assassinated, and the leaders were branded as "criminals" and Jews by the right-wing press dominated by Alfred Hugenberg.

Anti-Jewish sentiment was intensified by the Bavarian Soviet Republic (6 April – 3 May 1919), a communist government which briefly ruled the city of Munich before being crushed by the Freikorps.

[citation needed] In 1919, Deutschvölkischer Schutz und Trutzbund (German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation) leader Alfred Roth, writing under the pseudonym "Otto Arnim", published the book The Jew in the Army which he said was based on evidence gathered during his participation on the Judenzählung, a military census which had in fact shown that German Jews had served in the front lines proportionately to their numbers.

Roth's work claimed that most Jews involved in the war were only taking part as profiteers and spies, while he also blamed Jewish officers for fostering a defeatist mentality which impacted negatively on their soldiers.

[citation needed] German historian Friedrich Meinecke attempted to trace the roots of the expression "stab-in-the-back" in a 11 June 1922 article in the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse.

[citation needed] In the 1924 national election, the Munich cultural journal Süddeutsche Monatshefte published a series of articles blaming the SPD and trade unions for Germany's defeat in World War I, which came out during the trial of Hitler and Ludendorff for high treason following the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923.

[40] Historian Richard McMasters Hunt argues in a 1958 article that the myth was an irrational belief which commanded the force of irrefutable emotional convictions for millions of Germans.

Hunt argues that it was not the guilt of wickedness, but the shame of weakness that seized Germany's national psychology, and "served as a solvent of the Weimar democracy and also as an ideological cement of Hitler's dictatorship".