Battle of Stalingrad

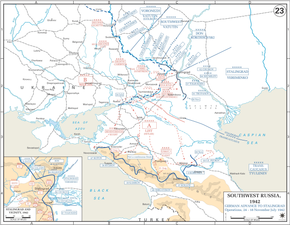

As the conflict progressed, Germany's fuel supplies dwindled and thus drove it to focus on moving deeper into Soviet territory and taking the country's oil fields at any cost.

By the spring of 1942, despite the failure of Operation Barbarossa to defeat the Soviet Union in a single campaign, the Wehrmacht had captured vast territories, including Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic republics.

The initial objectives around Stalingrad were to destroy the city's industrial capacity and block the Volga River traffic, crucial for connecting the Caucasus and Caspian Sea to central Russia.

"[74] Military historian David Glantz indicated that four hard-fought battles – collectively known as the Kotluban Operations – north of Stalingrad, where the Soviets made their greatest stand, decided Germany's fate before the Nazis ever set foot in the city itself, and were a turning point in the war.

The 369th (Croatian) Reinforced Infantry Regiment was the only non-German unit selected by the Wehrmacht to enter Stalingrad city during assault operations, with it fighting as part of the 100th Jäger Division.

Animals flee this hell; the hardest stones cannot bear it for long; only men endure.A ferocious battle raged for several days at the giant grain elevator in the south of the city.

[119] Mamayev Kurgan changed hands multiple times over the course of days, with fighting over the hill, rail station and Red Square being so intense that it was difficult to determine who was attacking and who was defending.

[132] The German onslaught crushed the 37th Guards Rifle Division of Major General Viktor Zholudev and in the afternoon the forward assault group reached the tractor factory before arriving at the Volga River, splitting the 62nd Army into two.

[143][144]: 265 As historian Chris Bellamy notes, the Germans paid a high strategic price for the aircraft sent into Stalingrad: the Luftwaffe was forced to divert much of its air strength away from the oil-rich Caucasus, which had been Hitler's original grand-strategic objective.

[146] In August 1942 after three months of slow advance, the Germans finally reached the river banks, capturing 90% of the ruined city and splitting the remaining Soviet forces into two narrow pockets.

As per Zhukov, "German operational blunders were aggravated by poor intelligence: they failed to spot preparations for the major counter-offensive near Stalingrad where there were 10 field, 1 tank and 4 air armies.

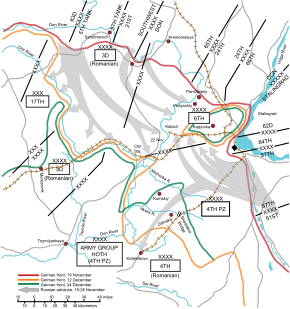

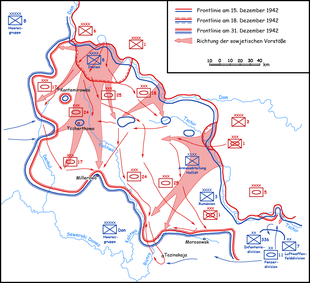

It aimed to break through to the Sixth Army and establish a corridor to keep it supplied and reinforced, so that, according to Hitler's order, it could maintain its "cornerstone" position on the Volga, "with regard to operations in 1943".

While a motorised breakout might have been possible in the first few weeks, the 6th Army now had insufficient fuel and the German soldiers would have faced great difficulty breaking through the Soviet lines on foot in harsh winter conditions.

"[188] The same day, Hermann Göring broadcast from the air ministry, comparing the situation of the surrounded German 6th Army to that of the Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae, the speech was not well received by soldiers however.

[191] Major Anatoly Soldatov described the conditions of the department store basement as such, "it was unbelievably filthy, you couldn't get through the front or back doors, the filth came up to your chest, along with human waste and who knows what else.

[200] The Soviets used the great amount of destruction to their advantage, by adding man-made defenses such as barbed wire, minefields, trenches, and bunkers to the rubble, while large factories even housed tanks and large-caliber guns within.

[211] The Soviet urban warfare tactics relied on 20-to-50-man-assault groups, armed with machine guns, grenades and satchel charges, with buildings fortified as strongpoints with clear fields of fire.

Antony Beevor describes how this process was particularly brutal, "In its way, the fighting in Stalingrad was even more terrifying than the impersonal slaughter at Verdun...It possessed a savage intimacy which appalled their generals, who felt that they were rapidly losing control over events.

Beevor noted the "sinister" message from the Stalingrad Front's Political Department on 8 October 1942 that: "The defeatist mood is almost eliminated and the number of treasonous incidents is getting lower" as an example of the coercion Red Army soldiers experienced under the Special Detachments (renamed SMERSH).

"[236] German observers were perplexed by the relentlessness of the Soviets, with a 29 October 1942 article in the SS newspaper, Das Schwarze Korps, stating "The Bolshevists attack until total exhaustion, and defend themselves until the physical extermination of the last man and weapon .

[251] The strain on military commanders was immense: Paulus developed an uncontrollable tic in his eye, which eventually affected the left side of his face, while Chuikov experienced an outbreak of eczema that required him to have his hands completely bandaged.

"[272] British historian Andrew Roberts stated that "Superlatives are unavoidable when describing the battle of Stalingrad; it was the struggle of Gog and Magog, the merciless clash where the rules of war were discarded .

[283] Russian historian Boris Vadimovich Sokolov cites the memoirs of a former director of the Tsaritsyn-Stalingrad Defense Museum, who noted that over two million Soviets dead were counted before being ordered to stop, with "still many months of work left".

[284] However, research by Russian historian Tatyana Pavlova calculated there to be 710,000 inhabitants in the city on 23 August, and of that amount, 185,232 people had died by the battle's conclusion, and including about 50,000 in the rural areas of Stalingrad, for a total of 235,232 civilians dead.

On 31 January, regular programmes on German state radio were replaced by a broadcast of the sombre Adagio movement from Anton Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, followed by the announcement of the defeat at Stalingrad.

[289] On 18 February, Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels gave the famous Sportpalast speech in Berlin, encouraging the Germans to accept a total war that would claim all resources and efforts from the entire population.

[296] Further, French historian François Kersaudy stated that "Stalingrad was unique in the Second World War, in terms of duration, the number of soldiers killed, the relentlessness, the significance" and that "It was terrifying on both sides.

According to Soviet intelligence documents shown in the documentary, a remarkable NKVD report from March 1943 is available showing the tenacity of some of these German groups: The mopping-up of counter-revolutionary elements in the city of Stalingrad proceeded.

[308] He remained in the Soviet Union until 1952, then moved to Dresden in East Germany, where he spent the remainder of his days defending his actions at Stalingrad and was quoted as saying that Communism was the best hope for postwar Europe.

Stalingrad has become synonymous with large-scale urban battles with immense casualties on both sides,[36][31][347][32][34] and according to historian David Glantz, has become a "metaphor for the ferocity of the Soviet-German conflict and, indeed, for the devastating nature of twentieth-century warfare as a whole".