History of Poland (1945–1989)

The new government solidified its political power, while the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) under Bolesław Bierut gained firm control over the country, which would remain an independent state within the Soviet sphere of influence.

[38][32][31] Beginning in late 1944, after the defeat of the Warsaw Uprising and the promotion of PKWN populist, the exiled government delegation from London was increasingly seen by Poles as a failed enterprise, its political-military organizations became isolated, and resistance against Communist political and administrative forces decisively weakened.

While Marxism–Leninism, the official ideology, was new to Poland, the communist regime continued, in many psychologically and practically important ways, the precepts, methods and manners of past Polish ruling circles, including those of the Sanation, the National Democracy, and 19th century traditions of cooperation with the partitioning powers.

For the party, the privileged nomenklatura layer was maintained to assure the proper placement of people who were ideologically reliable and otherwise qualified, but the revisionist dissidents Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski later described this system as a class dictatorship of central political bureaucracy for its own sake.

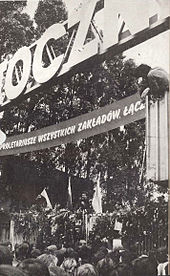

[107] Beginning on 28 June 1956, workers in the industrial city of Poznań, who had repeatedly but in vain petitioned the authorities to intervene and improve their deteriorating situation,[108] went on strike and rioted in response to a cut in wages and changed working conditions.

[112] Gomułka pledged to dismantle Stalinism and in his acceptance speech raised numerous social democratic-sounding reformist ideas, giving hope to the left-wing revisionists and others in Polish society that the communist state was, after all, reformable.

[41][71] In the communist era, because of their class role in the official ideology and leadership's sensibilities, workers enjoyed some clout and a degree of protection of their economic interests, on the condition that they refrained from engaging in independent politics or publicly exerting pressure.

[138] In fierce competition, the state authorities conducted their own national celebrations, stressing the origin of Polish statehood,[138] but the display of the Church hierarchy's command of enormous crowds in a land ruled by the communists must have impressed the Catholic prelates in the Vatican and elsewhere.

[143][u] In what became known as the March 1968 events, Moczar used the prior spontaneous and informal celebrations of the outcome of the Arab–Israeli Six-Day War of 1967 and now the Warsaw theatre affair as pretexts to launch an anti-intellectual and anti-Semitic (officially designated as "anti-Zionist") press campaign, whose real goal was to weaken the pro-reform liberal party faction and attack other circles.

[56][160] The effects of the 1973–74 oil crisis produced an inflationary surge followed by a recession in the West, which resulted in a sharp increase in the price of imported consumer goods in Poland, coupled with a decline in demand for Polish exports, particularly coal.

[159][163] In 1975, like other European countries, Poland became a signatory of the Helsinki Accords and member of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE); such developments were possible because of the period of "détente" between the Soviet Union and the United States.

[159] A series of "spontaneous" large scale public gatherings, intended to convey the "anger of the people" at the "trouble-makers" was staged by the party leadership in a number of cities, but the Soviet pressure prevented further attempts at raising prices.

Western financial companies and institutions providing loans to the regime at a meeting at the Bank Handlowy in Warsaw on 24 April 1980[180] The bankers made it clear that the state could no longer subsidize artificially low prices of consumer goods.

[191] In 1981, Solidarity accepted the necessity of assuming a political role and helped form a broad anti-ruling system social movement, dominated by the working class and with members ranging from people associated with the Catholic Church to non-communist leftists.

[115][p] The activity of Solidarity, although concerned with trade union matters (such as replacing the nomenklatura-run system with worker self-management in enterprise-level decision making),[h] was widely regarded as the first step towards dismantling the regime's dominance over social institutions, professional organizations and community associations.

During a conference of Solidarity's National Commission (a central representative policy making body) that followed, Modzelewski, Kuroń and others proposed a democratic transformation and practical arrangements by which the Union would take upon itself a major political role, participating in governing the country, accepting responsibility for the outcome and keeping social peace, thus relieving the ruling party of some of its burdens.

[202] At the State Defense Committee meeting on 13 September (the time of the Soviet Exercise Zapad-81 maneuvers and of renewed pressure on the Polish leadership), Kania was warned by the uniformed cadres that the progressing counterrevolution must be terminated by an imposition of martial law.

[226][230] The practice of centralized economic decision making had not been overcome, while the newly autonomous enterprises moved toward a rather spontaneous and chaotic partial privatization of dubious legality; it included elements of kleptocracy and had a significant middle-level nomenklatura component.

Solidarity as such, a labor union representing workers' interests, was unable to reassert itself after the martial law and later in the 1980s was practically destroyed, but preserved in the national consciousness as a myth that facilitated social acceptance of systemic changes previously deemed unthinkable.

With his support for Polish and Hungarian membership in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and for the Eastern European pluralistic evolution in general, the Soviet leader effectively pushed the region toward the West.

[169][227] The strikes were the last act of active political involvement of the working class in the history of People's Poland and were led by young workers, not connected to Solidarity veterans and opposed to socially harmful consequences of the economic restructuring that was in progress at that time.

[227][244] During the PZPR's plenary session of 16–18 January 1989, General Jaruzelski and his ruling formation overcame the Central Committee's resistance by threatening to resign and the party decided to allow re-legalization of Solidarity and to approach its leaders for formal talks.

[252] Mazowiecki's government, forced to deal quickly with galloping hyperinflation, soon adopted radical economic policies, proposed by Leszek Balcerowicz, which transformed Poland into a functioning market economy under an accelerated schedule.

[242][253] The economic reform, a shock therapy accompanied by comprehensive neoliberal restructuring,[254] was, in reality, an extension of the previous incremental "communist" policies of the 1970s and 1980s, which were now followed by a leap to greatly expanded integration with the global economy with little protection.

[228][230][240][242][257][c][f] The striking electoral victory of Solidarity candidates in the limited elections, and the subsequent formation of the first non-communist government in the region in decades, encouraged many similar peaceful transitions from communist party rule in Central and Eastern Europe in the second half of 1989.

Their socially detrimental consequences included the lasting political polarization over the practically limited range of choices: economic liberalism lacking any communal concerns on the one hand, and the conservative, patriarchal and parochial backwaters of Polish nationalism on the other.

[280] n.^ Polish intellectuals and leaders of the 1980s were affected by the shifted economic and political thinking in the West, now dominated by the neoliberal and neoconservative policies of Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

Later in the 1980s and in the 1990s workers will be defined by intellectuals as irrational, misguided and even dangerous, because of their "illegitimate" opposition to the "necessary", "correct" and "rational" economic policies, pursued especially by the new post-1989 liberal establishment and couched by it in the absolute language of science, not in relative terms of a political debate.

The abandonment, rejection and exclusion would thus push many workers, labor activists and others into right-wing populism and religious nationalism (the marginalized in 1989 but later resurgent illiberal camp), while the liberal elite would pay with a steady erosion of its authority.

However, the cost for the Left was a surrender of its fundamental value system (the mainstream opposition could thus no longer be considered leftist), and in the long run granting the Right the upper hand in the ability to mobilize mass political support.