Standard Oil

The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founded in 1870 by John D. Rockefeller.

[8] Jersey Standard operated a near monopoly in the American oil industry from 1899 until 1911 and was the largest corporation in the United States.

The charge against Jersey came about in part as a consequence of the reporting of Ida Tarbell, who wrote The History of the Standard Oil Company.

[12] In the early years, John D. Rockefeller dominated the combine; he was the single most important figure in shaping the new oil industry.

In a seminal deal, in 1868, the Lake Shore Railroad, a part of the New York Central, gave Rockefeller's firm a going rate of one cent a gallon or forty-two cents a barrel, an effective 71% discount from its listed rates in return for a promise to ship at least 60 carloads of oil daily and to handle loading and unloading on its own.

[citation needed] Smaller companies decried such deals as unfair because they were not producing enough oil to qualify for discounts.

[16] Rockefeller used the Erie Canal as a cheap alternative form of transportation—in the summer months when it was not frozen—to ship his refined oil from Cleveland to the industrialized Northeast.

[20] In response to state laws that had the result of limiting the scale of companies, Rockefeller and his associates developed innovative ways of organizing to effectively manage their fast-growing enterprise.

By 1882, Rockefeller's top aide was John Dustin Archbold, whom he left in control after disengaging from business to concentrate on philanthropy after 1896.

In 1890, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Sherman Antitrust Act (Senate 51–1; House 242–0), a source of American anti-monopoly laws.

The Standard Oil group quickly attracted attention from antitrust authorities leading to a lawsuit filed by Ohio Attorney General David K. Watson.

In 1896, John Rockefeller retired from the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey, the holding company of the group, but remained president and a major shareholder.

Her work was published in 19 parts in McClure's magazine from November 1902 to October 1904, then in 1904 as the book The History of the Standard Oil Co.

They made large purchases of stock in U.S. Steel, Amalgamated Copper, and even Corn Products Refining Co.[29] Weetman Pearson, a British petroleum entrepreneur in Mexico, began negotiating with Standard Oil in 1912–13 to sell his "El Aguila" oil company, since Pearson was no longer bound to promises to the Porfirio Díaz regime (1876–1911) to not to sell to U.S. interests.

[30] Standard Oil's production increased so rapidly it soon exceeded U.S. demand, and the company began viewing export markets.

In the 1890s, Standard Oil began marketing kerosene to China's large population of close to 400 million as lamp fuel.

[36] Stanvac's North China Division, based in Shanghai, owned hundreds of vessels, including motor barges, steamers, launches, tugboats, and tankers.

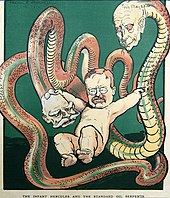

According to Daniel Yergin in his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (1990), this conglomerate was seen by the public as all-pervasive, controlled by a select group of directors, and completely unaccountable.

[44] The federal Commissioner of Corporations studied Standard's operations from the period of 1904 to 1906[45] and concluded that "beyond question ... the dominant position of the Standard Oil Co. in the refining industry was due to unfair practices—to abuse of the control of pipe-lines, to railroad discriminations, and to unfair methods of competition in the sale of the refined petroleum products".

[46] Because of competition from other firms, their market share gradually eroded to 70 percent by 1906 which was the year when the antitrust case was filed against Standard.

[citation needed] In 1909, the U.S. Justice Department sued Standard under federal antitrust law, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, for sustaining a monopoly and restraining interstate commerce by: Rebates, preferences, and other discriminatory practices in favor of the combination by railroad companies; restraint and monopolization by control of pipe lines, and unfair practices against competing pipe lines; contracts with competitors in restraint of trade; unfair methods of competition, such as local price cutting at the points where necessary to suppress competition; [and] espionage of the business of competitors, the operation of bogus independent companies, and payment of rebates on oil, with the like intent.

In almost every section of the country that company has been found to enjoy some unfair advantages over its competitors, and some of these discriminations affect enormous areas.

[51]The government said that Standard raised prices to its monopolistic customers but lowered them to hurt competitors, often disguising its illegal actions by using bogus, supposedly independent companies it controlled.

The evidence is, in fact, absolutely conclusive that the Standard Oil Co. charges altogether excessive prices where it meets no competition, and particularly where there is little likelihood of competitors entering the field, and that, on the other hand, where competition is active, it frequently cuts prices to a point which leaves even the Standard little or no profit, and which more often leaves no profit to the competitor, whose costs are ordinarily somewhat higher.

[57] In the Asia-Pacific region, Jersey Standard had oil production and refineries in the Dutch East Indies but no marketing network.

[61] An example of this thinking was given in 1890, when Rep. William Mason, arguing in favor of the Sherman Antitrust Act, said: "trusts have made products cheaper, have reduced prices; but if the price of oil, for instance, were reduced to one cent a barrel, it would not right the wrong done to people of this country by the trusts which have destroyed legitimate competition and driven honest men from legitimate business enterprise".

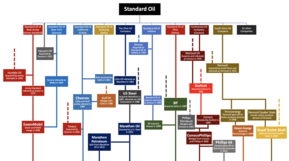

[63] Some analysts argue that the breakup was beneficial to consumers in the long run, and no one has ever proposed that Standard Oil be reassembled in pre-1911 form.

Since the breakup of Standard Oil, several companies, such as General Motors and Microsoft, have come under antitrust investigation for being inherently too large for market competition; however, most of them remained together.

In February 2016, ExxonMobil successfully asked a U.S. federal court to lift the 1930s trademark injunction that banned it from using the Esso brand in some states.

Chevron withdrew from Kentucky (home of the Standard Oil of Kentucky, which Chevron acquired in 1961) in 2010, while BP gradually withdrew from five Great Plains and Rocky Mountain states (Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) since the initial conversion of Amoco sites to BP.