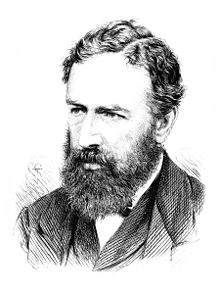

William Stanley Jevons

Jevons' work, along with similar discoveries made by Carl Menger in Vienna (1871) and by Léon Walras in Switzerland (1874), marked the opening of a new period in the history of economic thought.

Jevons's contribution to the marginal revolution in economics in the late 19th century established his reputation as a leading political economist and logician of the time.

Jevons broke off his studies of the natural sciences in London in 1854 to work as an assayer in Sydney, where he acquired an interest in political economy.

[6]: 295f [7]: 147 [5]: 2 The most important of his works on logic and scientific methods is his Principles of Science (1874),[8] as well as The Theory of Political Economy (1871) and The State in Relation to Labour (1882).

Towards the end of 1853, after having spent two years at University College, where his favourite subjects were chemistry and botany, he received an offer as metallurgical assayer for the new mint in Australia.

The idea of leaving the UK was distasteful, but pecuniary considerations had, in consequence of the failure of his father's firm in 1847, become of vital importance, and he accepted the post.

Jevons lived with his colleague and his wife first at Church Hill, then in Annangrove at Petersham and at Double Bay before returning to England.

[9] It was not until after the publication of this work that Jevons became acquainted with the applications of mathematics to political economy made by earlier writers, notably Antoine Augustin Cournot and H.H.

The theory of utility was at about 1870 being independently developed on somewhat similar lines by Carl Menger in Austria and Léon Walras in Switzerland.

In his reaction from the prevailing view he sometimes expressed himself without due qualification: the declaration, for instance, made at the commencement of the Theory of Political Economy, that value depends entirely upon utility, lent itself to misinterpretation.

For example, in "The Theory of Political Economy", Chapter II, the subsection on "Theory of Dimensions of Economic Quantities", Jevons makes the statement that "In the first place, pleasure and pain must be regarded as measured upon the same scale, and as having, therefore, the same dimensions, being quantities of the same kind, which can be added and subtracted...." Speaking of measurement, addition and subtraction requires cardinality, as does Jevons's heavy use of integral calculus.

A Serious Fall in the Value of Gold (1863) and The Coal Question (1865) placed him in the front rank as a writer on applied economics and statistics; and he would be remembered as one of the leading economists of the 19th century even had his Theory of Political Economy never been written.

His economic works include Money and the Mechanism of Exchange (1875) written in a popular style, and descriptive rather than theoretical; a Primer on Political Economy (1878); The State in Relation to Labour (1882), and two works published after his death, Methods of Social Reform" and "Investigations in Currency and Finance, containing papers that had appeared separately during his lifetime.

[12] In 1875, Jevons read a paper On the influence of the sun-spot period upon the price of corn at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

This captured the attention of the media and led to the coining of the word sunspottery for claims of links between various cyclic events and sun-spots.

In 1866 what he regarded as the great and universal principle of all reasoning dawned upon him; and in 1869 Jevons published a sketch of this fundamental doctrine under the title of The Substitution of Similars.

"Though less attractively written than Mill's System of Logic, Principles of Science is a book that keeps much closer to the facts of scientific practice.

His strength lay in his power as an original thinker rather than as a critic; and he will be remembered by his constructive work as logician, economist and statistician.

He then extended this argument into three dimensions, noting that this raises fundamental questions of the relationship of spatial perception to mathematical truth.

This conversation between Helmholtz and Jevons was a microcosm of an ongoing debate between truth and perception in the wake of the introduction of non-Euclidean geometry in the late 19th century.

Jevons suffered from ill health and sleeplessness, and found the delivery of lectures covering so wide a range of subjects very burdensome.

He found his professorial duties increasingly irksome, and feeling that the pressure of literary work left him no spare energy, he decided in 1880 to resign the post.

Alfred Marshall said of his work in economics that it "will probably be found to have more constructive force than any, save that of Ricardo, that has been done during the last hundred years.