Real business-cycle theory

[1] RBC theory sees business cycle fluctuations as the efficient response to exogenous changes in the real economic environment.

In RBC models, business cycles are described as "real" because they reflect optimal adjustments by economic agents rather than failures of markets to clear.

As a result, RBC theory suggests that governments should concentrate on long-term structural change rather than intervention through discretionary fiscal or monetary policy.

This occurs for two reasons: A common way to observe such behavior is by looking at a time series of an economy's output, more specifically gross national product (GNP).

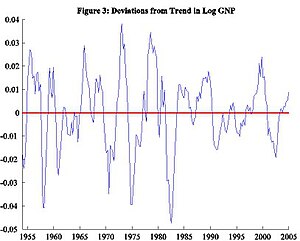

Using log real GNP, the distance between any point and the 0 line roughly equals the percentage deviation from the long-run growth trend.

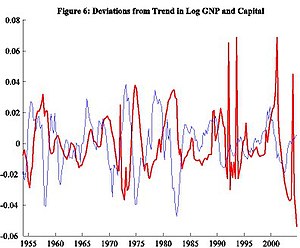

For example, consider Figure 4, which depicts fluctuations in output and consumption spending, i.e., what people buy and use at any given period.

An acyclical variable with a correlation close to zero implies no systematic relationship to the business cycle.

Observing these similarities yet seemingly non-deterministic fluctuations in trends, the question arises as to why this occurs.

Since people prefer economic booms over recessions, if everyone in the economy makes optimal decisions, these fluctuations are caused by something outside the decision-making process.

The one which currently dominates the academic literature on real business cycle theory[citation needed] was introduced by Finn E. Kydland and Edward C. Prescott in their 1982 work Time to Build And Aggregate Fluctuations.

They envisioned this factor as technological shocks—i.e., random fluctuations in the productivity level that shifted the constant growth trend up or down.

Examples of such shocks include innovations, bad weather, increased imports oil price, stricter environmental and safety regulations, etc.

Given these shocks, RBC models predict time sequences of allocation for consumption, investment, etc.

Instead, he may consume some but invest the rest in capital to enhance production in subsequent periods and thus increase future consumption.

The basic RBC model predicts that given a temporary shock, output, consumption, investment,t, and labor, all rise above their long-term trends and formative deviation.

This capital accumulation is often referred to as an internal "propagation mechanism" since it may increase the persistence of shocks to output.

To quantitatively match the stylized facts in Table 1, Kydland and Prescott introduced calibration techniques.

Yet current RBC models have not fully explained all behavior, and neoclassical economists are still searching for better variations.

The main assumption in RBC theory is that individuals and firms respond optimally over the long run.

This suggests laissez-faire (non-intervention) is the best policy of the government towards the economy, but given the abstract nature of the model, this has been debated.

A precursor to RBC theory was developed by monetary economists Milton Friedman and Robert Lucas in the early 1970s.

[citation needed] If the full range of possible values for these variables is used, correlation coefficients between actual and simulated paths of economic variables can shift wildly, leading some to question how successful a model that only achieves a coefficient of 80% is.

[citation needed] The real business cycle theory relies on three assumptions which, according to economists such as Greg Mankiw and Larry Summers, are unrealistic:[2] 1.

Another major criticism is that real business cycle models can not account for the dynamics displayed by the U.S. gross national product.