Ancient Chinese states

Once the Zhou had established themselves, they made grants of land and relative local autonomy to kinfolk in return for military support and tributes, under a system known as fengjian.

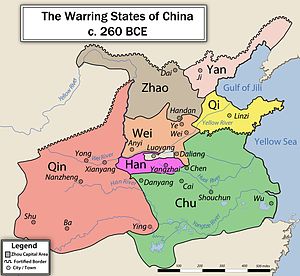

Over time, the smaller polities were absorbed by the larger ones, either by force or willing submission, until only one remained: Qin (秦), which unified the realm in 221 BCE and became China's first imperial dynasty.

The Zhou dynasty grew out of a predynastic polity with its own existing power structure, primarily organized as a set of culturally affiliated kinship groups.

[3] The regional lords were established to provide a screen to the royal lands and exert control over culturally distinct polities and were mostly defined by that responsibility, but this was also embedded in the kinship groups.

The state of Song (宋) was permitted to be retained by the nobility of the defeated Shang dynasty, in what would become a custom known as Er Wang San Ke.

These polities and cultural outgroups in the Yangtze River valley were not fully incorporated into a centralised political domain until the imperial era.

Over time the parcels of land the royal court was able to grant became increasingly small, and population growth and associated socioeconomic pressures strained the Zhou confederation and the power of the central government.

Canny clans formed alliances through marriage, powerful ministers began to overshadow the kings, and eventually a succession crisis brought an end to the Western Zhou period.

After an attack by Quanrong nomads allied with several vassal states including Shen (申) and Zheng (鄭) in 771 BCE, the Zhou ruler King You was killed in his palace at Haojing.

[9][10] The scale of the division of loyalties between the regional states, and the effect it had on society is not clear, but archaeology attests significant movement of people around this time.

[11] With the primary capital moved from Haojing to Luoyi, after a succession crisis of indeterminate severity, the royal house had lost its power and almost all of its land.

The prestige of the king, as Heaven's eldest son, was not significantly diminished, and he retained his ritual authority within the Ji lineage, but he and his family were much more reliant on the regional states.

[11] The regional states, now operating more autonomously than ever, had to invent ways to interact diplomatically, and they began to systematize a set of ranks amongst them, meet for interstate conferences, build great walls of rammed earth, and absorb one another.

Soon after, King Hui of Zhou conferred the title of bà (hegemon), giving Duke Huan royal authority in military ventures.

[17] In the case of Jin, the shift happened in 588 when the army was split into six independent divisions, each dominated by a separate noble family: Zhi (智), Zhao (趙), Han (韓), Wei (魏), Fan (范), and Zhonghang (中行).

A new class of gentlemen-scholars, distantly related to the aristocracy but part of the elite culture nonetheless, formed the basis of this extended bureaucracy, their goal of upward social mobility expressed through participation in officialdom.

He forced all the conquered leaders to attend the capital where he seized their states and turned them into administrative districts classified as either commanderies or counties depending on their size.