Steam spring

The vertical forces of the moving pistons further gave rise to hammer blow, which increased the load on the rails.

[2] The ability of an 'adhesion-hauled' locomotive to draw a train was much questioned at this time, as it was thought that the friction between a smooth iron wheel and the rail would be inadequate.

Stephenson believed that, provided a good contact could be maintained between wheel and rail, frictional adhesion alone would be adequate.

Inside each cylinder a piston carried the load of the axle and pressed upwards against steam pressure within the boiler.

Those for large stationary engines, working at low pressures, were sealed by a variety of methods including leather cup washers, pools of standing water and even a poultice of cow dung.

Despite this, they continued to give trouble with leakage and were eventually removed and replaced with iron or steel leaf springs.

It suffered from poor traction on the relatively new technology of edge rails with flanged wheels, put down to the problem of maintaining a good contact with them.

It was sold to the Earl of Elgin in October 1824 for his railway in Fife, but being too heavy for the rails was used as a stationary pumping engine in a quarry at Charlestown, and from 1830 at a colliery near Dunfermline; its subsequent fate is unrecorded.

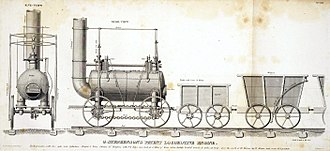

Most Scottish depictions of The Duke are inaccurate, being based on the Killingworth locomotives or even Stephenson's Rocket, but in 1914 a commemorative silver model was made for the centenary and this alone seems accurate, showing the six wheels and the cylinders of the steam springs.

The presence of this cannon box between the wheels also prevented the previous use of the central drive chain and so Stephenson adopted the now ubiquitous coupling rods for his first time.

Reducing the travel of the suspension, compared to that with steam springs, also made the provision of free-running coupling rods easier, as it avoided the change in effective wheelbase when one axle moved relative to the other.