Steele's Greenville expedition

[10] Steele's troops left the Young's Point, Louisiana,[a] area late on April 2, heading upriver via steamboats.

While much of Steele's force remained in the Washington's Landing area, detachments patrolled inward, learning that the path to Deer Creek was flooded.

Two regiments and the Union Navy tinclad steamer USS Prairie Bird were left at the landing point to guard it.

Ferguson had known of the Union presence since not long after the landing, and he sent a messenger to Major General Carter L. Stevenson at Vicksburg, asking for instructions.

Stevenson detached the brigade of Brigadier General Stephen Dill Lee to the area, with orders to secure Rolling Fork and then move up the Bogue Phalia stream and strike Steele's rear.

[16] More reinforcements were positioned at Snyder's Bluff and along the Sunflower River, and some cottonclad gunboats were shifted southwards in response to the threat.

Ferguson also sent a task force to a bend on the Mississippi River with instructions to cut a levee near Black Bayou, with the intent of flooding the terrain in the area, particularly where a road in Steele's rear crossed a swamp.

[20] Steele, in turn, deployed artillery and prepared to make an attack, but Ferguson withdrew,[21] 6 miles (9.7 km) south to the Willis plantation.

[23] Steele halted the pursuit on the morning on April 8, and his troops confiscated and destroyed goods found on the plantations in the area.

[30] Steele did not want this,[25] and encouraged them to remain on plantations; when the campaign began, he had been ordered to discourage slaves from fleeing to Union lines.

Ferguson had withdrawn his troops, but left behind large quantities of supplies and cattle, which the Union soldiers found and brought back to camp.

[34] In the words of James H. Wilson, Steele's Greenville expedition made the Union army an implement of "agricultural disorganization and distress as well as of emancipation".

[37] In an earlier communication, Henry Halleck (who had been appointed General-in-Chief of the Union Army in July 1862) had written to Grant that he believed that there would be "no peace but that which is forced by the sword".

In the future, in the words of Shea and Winschel, the Union army brought "the war home to [Confederate] civilians by enforcing emancipation and seizing or destroying all items of possible military value".

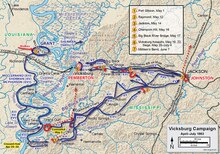

After the action at Raymond, Grant decided to strike a Confederate force forming at Jackson, Mississippi, and then turn west towards Vicksburg.