Star formation

Spiral galaxies like the Milky Way contain stars, stellar remnants, and a diffuse interstellar medium (ISM) of gas and dust.

The interstellar medium consists of 104 to 106 particles per cm3, and is typically composed of roughly 70% hydrogen, 28% helium, and 1.5% heavier elements by mass.

Higher density regions of the interstellar medium form clouds, or diffuse nebulae,[3] where star formation takes place.

[4] The Herschel Space Observatory has revealed that filaments, or elongated dense gas structures, are truly ubiquitous in molecular clouds and central to the star formation process.

Continuous accretion of gas, geometrical bending[definition needed], and magnetic fields may control the detailed manner in which the filaments are fragmented.

[11] However, lower mass star formation is occurring about 400–450 light-years distant in the ρ Ophiuchi cloud complex.

[4] During cloud collapse dozens to tens of thousands of stars form more or less simultaneously which is observable in so-called embedded clusters.

[18] In triggered star formation, one of several events might occur to compress a molecular cloud and initiate its gravitational collapse.

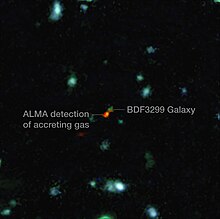

Alternatively, galactic collisions can trigger massive starbursts of star formation as the gas clouds in each galaxy are compressed and agitated by tidal forces.

[21] A supermassive black hole at the core of a galaxy may serve to regulate the rate of star formation in a galactic nucleus.

A black hole that is accreting infalling matter can become active, emitting a strong wind through a collimated relativistic jet.

Massive black holes ejecting radio-frequency-emitting particles at near-light speed can also block the formation of new stars in aging galaxies.

These processes absorb the energy of the contraction, allowing it to continue on timescales comparable to the period of collapse at free fall velocities.

[30] This continues until the gas is hot enough for the internal pressure to support the protostar against further gravitational collapse—a state called hydrostatic equilibrium.

When the density and temperature are high enough, deuterium fusion begins, and the outward pressure of the resultant radiation slows (but does not stop) the collapse.

The energy source of these objects is (gravitational contraction)Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism, as opposed to hydrogen burning in main sequence stars.

The protostellar stage of stellar existence is almost invariably hidden away deep inside dense clouds of gas and dust left over from the GMC.

[36] Observations from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) have thus been especially important for unveiling numerous galactic protostars and their parent star clusters.

[39] The structure of the molecular cloud and the effects of the protostar can be observed in near-IR extinction maps (where the number of stars are counted per unit area and compared to a nearby zero extinction area of sky), continuum dust emission and rotational transitions of CO and other molecules; these last two are observed in the millimeter and submillimeter range.

[44] X-ray observations have provided near-complete censuses of all stellar-mass objects in the Orion Nebula Cluster and Taurus Molecular Cloud.

[47] On February 21, 2014, NASA announced a greatly upgraded database for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe.

[48] In February 2018, astronomers reported, for the first time, a signal of the reionization epoch, an indirect detection of light from the earliest stars formed - about 180 million years after the Big Bang.

[49] An article published on October 22, 2019, reported on the detection of 3MM-1, a massive star-forming galaxy about 12.5 billion light-years away that is obscured by clouds of dust.

As described above, the collapse of a rotating cloud of gas and dust leads to the formation of an accretion disk through which matter is channeled onto a central protostar.

[65] Recent studies have emphasized the role of filamentary structures in molecular clouds as the initial conditions for star formation.

Findings from the Herschel Space Observatory highlight the ubiquitous nature of these filaments in the cold interstellar medium (ISM).

This supports the hypothesis that filamentary structures act as pathways for the accumulation of gas and dust, leading to core formation.