Stellar parallax

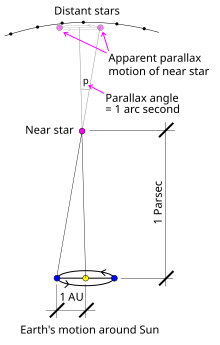

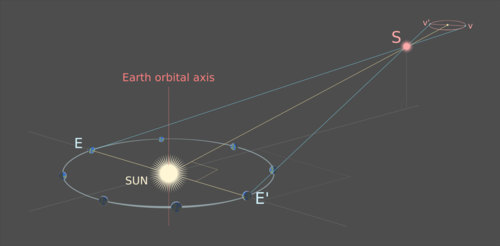

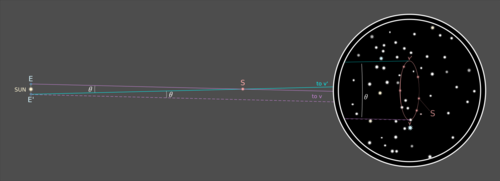

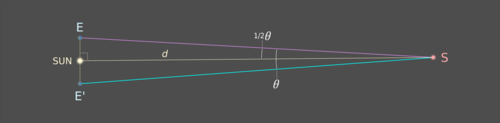

The parallax itself is considered to be half of this maximum, about equivalent to the observational shift that would occur due to the different positions of Earth and the Sun, a baseline of one astronomical unit (AU).

Stellar parallax is so difficult to detect that its existence was the subject of much debate in astronomy for hundreds of years.

Stellar parallax is so small that it was unobservable until the 19th century, and its apparent absence was used as a scientific argument against heliocentrism during the early modern age.

It is clear from Euclid's geometry that the effect would be undetectable if the stars were far enough away, but for various reasons, such gigantic distances involved seemed entirely implausible: it was one of Tycho Brahe's principal objections to Copernican heliocentrism that for it to be compatible with the lack of observable stellar parallax, there would have to be an enormous and unlikely void between the orbit of Saturn and the eighth sphere (the fixed stars).

The stellar movement proved too insignificant for his telescope, but he instead discovered the aberration of light[2] and the nutation of Earth's axis, and catalogued 3,222 stars.

In the second quarter of the 19th century, technological progress reached to the level which provided sufficient accuracy and precision for stellar parallax measurements.

[4][5] Between 1835 and 1836, astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve at the Dorpat university observatory measured the distance of Vega, publishing his results in 1837.

[6] Friedrich Bessel, a friend of Struve, carried out an intense observational campaign in 1837–1838 at Koenigsberg Observatory for the star 61 Cygni using a heliometer, and published his results in 1838.

[9] A large heliometer was installed at Kuffner Observatory (In Vienna) in 1896, and was used for measuring the distance to other stars by trigonometric parallax.

Automated plate-measuring machines[11] and more sophisticated computer technology of the 1960s allowed more efficient compilation of star catalogues.

In the 1980s, charge-coupled devices (CCDs) replaced photographic plates and reduced optical uncertainties to one milliarcsecond.

[citation needed] Stellar parallax remains the standard for calibrating other measurement methods (see Cosmic distance ladder).

The Hubble telescope WFC3 now has a precision of 20 to 40 microarcseconds, enabling reliable distance measurements up to 3,066 parsecs (10,000 ly) for a small number of stars.

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft performed the first interstellar parallax measurement on 22 April 2020, taking images of Proxima Centauri and Wolf 359 in conjunction with earth-based observatories.

[15] The European Space Agency's Gaia mission, launched 19 December 2013, is expected to measure parallax angles to an accuracy of 10 microarcseconds for all moderately bright stars, thus mapping nearby stars (and potentially planets) up to a distance of tens of thousands of light-years from Earth.

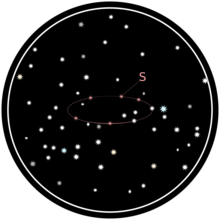

Annual parallax is normally measured by observing the position of a star at different times of the year as Earth moves through its orbit.