Rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water).

In basic form, a rudder is a flat plane or sheet of material attached with hinges to the craft's stern, tail, or afterend.

[1] More specifically, the steering gear of ancient vessels can be classified into side-rudders and stern-mounted rudders, depending on their location on the ship.

The steering oar can interfere with the handling of the sails (limiting any potential for long ocean-going voyages) while it was fit more for small vessels on narrow, rapid-water transport; the rudder did not disturb the handling of the sails, took less energy to operate by its helmsman, was better fit for larger vessels on ocean-going travel, and first appeared in ancient China during the 1st century AD.

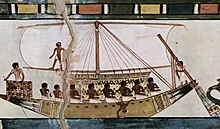

Rowing oars set aside for steering appeared on large Egyptian vessels long before the time of Menes (3100 BC).

[20][21] In Iran, oars mounted on the side of ships for steering are documented from the 3rd millennium BCE in artwork, wooden models, and even remnants of actual boats.

[22] By the first half of the 1st century AD, steering gear mounted on the stern were also quite common in Roman river and harbour craft as proved from reliefs and archaeological finds (Zwammerdam, Woerden 7).

A tomb plaque of Hadrianic age shows a harbour tug boat in Ostia with a long stern-mounted oar for better leverage.

[30] The world's oldest known depiction of a sternpost-mounted rudder can be seen on a pottery model of a Chinese junk dating from the 1st century AD during the Han dynasty, predating their appearance in the West by a thousand years.

[7][11][31] In China, miniature models of ships that feature steering oars have been dated to the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BC).

[31] Chinese rudders are attached to the hull by means of wooden jaws or sockets,[34] while typically larger ones were suspended from above by a rope tackle system so that they could be raised or lowered into the water.

Detailed descriptions of Chinese junks during the Middle Ages are known from various travellers to China, such as Ibn Battuta of Tangier, Morocco and Marco Polo of Venice, Italy.

The later Chinese encyclopedist Song Yingxing (1587–1666) and the 17th-century European traveler Louis Lecomte wrote of the junk design and its use of the rudder with enthusiasm and admiration.

[31] A Chandraketugarh (West Bengal) seal dated between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD depicts a steering mechanism on a ship named ''Indra of the Ocean'' (Jaladhisakra), which indicates that it was a sea-bound vessel.

As the size of ships and the height of the freeboards increased, quarter steering oars became unwieldy and were replaced by the more sturdy rudders with pintle and gudgeon attachment.

[41] Historian Joseph Needham holds that the stern-mounted rudder was transferred from China to Europe and the Islamic world during the Middle Ages.

Better performance with faster handling characteristics can be provided by skeg hung rudders on boats with smaller fin keels.

Small boat rudders that can be steered more or less perpendicular to the hull's longitudinal axis make effective brakes when pushed "hard over."