Stochastic dominance

Stochastic dominance is a partial order between random variables.

The concept arises in decision theory and decision analysis in situations where one gamble (a probability distribution over possible outcomes, also known as prospects) can be ranked as superior to another gamble for a broad class of decision-makers.

It is based on shared preferences regarding sets of possible outcomes and their associated probabilities.

Only limited knowledge of preferences is required for determining dominance.

Risk aversion is a factor only in second order stochastic dominance.

Stochastic dominance does not give a total order, but rather only a partial order: for some pairs of gambles, neither one stochastically dominates the other, since different members of the broad class of decision-makers will differ regarding which gamble is preferable without them generally being considered to be equally attractive.

Stochastic dominance could trace back to (Blackwell, 1953),[3] but it was not developed until 1969–1970.

In the case of non-intersecting[clarification needed] distribution functions, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test tests for first-order stochastic dominance.

are both finite, then the following conditions are equivalent, thus they may all serve as the definition of first-order stochastic dominance:[7] The first definition states that a gamble

The third definition states that we can construct a pair of gambles

Consider three gambles over a single toss of a fair six-sided die: Gamble A statewise dominates gamble B because A gives at least as good a yield in all possible states (outcomes of the die roll) and gives a strictly better yield in one of them (state 3).

In general, although when one gamble first-order stochastically dominates a second gamble, the expected value of the payoff under the first will be greater than the expected value of the payoff under the second, the converse is not true: one cannot order lotteries with regard to stochastic dominance simply by comparing the means of their probability distributions.

For instance, in the above example C has a higher mean (2) than does A (5/3), yet C does not first-order dominate A.

if the former is more predictable (i.e. involves less risk) and has at least as high a mean.

All risk-averse expected-utility maximizers (that is, those with increasing and concave utility functions) prefer a second-order stochastically dominant gamble to a dominated one.

Second-order dominance describes the shared preferences of a smaller class of decision-makers (those for whom more is better and who are averse to risk, rather than all those for whom more is better) than does first-order dominance.

Second-order stochastic dominance can also be expressed as follows: Gamble

disliked by those with an increasing utility function), and the introduction of random variable

are both finite, then the following conditions are equivalent, thus they may all serve as the definition of second-order stochastic dominance:[7] These are analogous with the equivalent definitions of first-order stochastic dominance, given above.

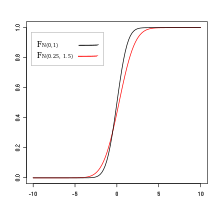

be the cumulative distribution functions of two distinct investments

Higher orders of stochastic dominance have also been analyzed, as have generalizations of the dual relationship between stochastic dominance orderings and classes of preference functions.

[12] Arguably the most powerful dominance criterion relies on the accepted economic assumption of decreasing absolute risk aversion.

[13][14] This involves several analytical challenges and a research effort is on its way to address those.

[15] Formally, the n-th-order stochastic dominance is defined as [16]

stochastically dominates a fixed random benchmark

In these problems, utility functions play the role of Lagrange multipliers associated with stochastic dominance constraints.

If the first order stochastic dominance constraint is employed, the utility function

is nondecreasing; if the second order stochastic dominance constraint is used,

A system of linear equations can test whether a given solution if efficient for any such utility function.

[20] Third-order stochastic dominance constraints can be dealt with using convex quadratically constrained programming (QCP).