Stokes' theorem

is defined and has continuous first order partial derivatives in a region containing

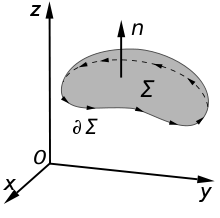

The main challenge in a precise statement of Stokes' theorem is in defining the notion of a boundary.

One (advanced) technique is to pass to a weak formulation and then apply the machinery of geometric measure theory; for that approach see the coarea formula.

In this article, we instead use a more elementary definition, based on the fact that a boundary can be discerned for full-dimensional subsets of

It now suffices to transfer this notion of boundary along a continuous map to our surface in

Stokes' theorem can be viewed as a special case of the following identity:[9]

is a uniform scalar field, the standard Stokes' theorem is recovered.

[10] When proving this theorem, mathematicians normally deduce it as a special case of a more general result, which is stated in terms of differential forms, and proved using more sophisticated machinery.

While powerful, these techniques require substantial background, so the proof below avoids them, and does not presuppose any knowledge beyond a familiarity with basic vector calculus and linear algebra.

[note 3] Recognizing that the columns of Jyψ are precisely the partial derivatives of ψ at y, we can expand the previous equation in coordinates as

First, calculate the partial derivatives appearing in Green's theorem, via the product rule:

Conveniently, the second term vanishes in the difference, by equality of mixed partials.

Note that x ↦ a × x is linear, so it is determined by its action on basis elements.

We can now recognize the difference of partials as a (scalar) triple product:

Combining the second and third steps and then applying Green's theorem completes the proof.

Green's theorem asserts the following: for any region D bounded by the Jordans closed curve γ and two scalar-valued smooth functions

This concept is very fundamental in mechanics; as we'll prove later, if F is irrotational and the domain of F is simply connected, then F is a conservative vector field.

In classical mechanics and fluid dynamics it is called Helmholtz's theorem.

be an open subset with a lamellar vector field F and let c0, c1: [0, 1] → U be piecewise smooth loops.

Some textbooks such as Lawrence[5] call the relationship between c0 and c1 stated in theorem 2-1 as "homotopic" and the function H: [0, 1] × [0, 1] → U as "homotopy between c0 and c1".

Above Helmholtz's theorem gives an explanation as to why the work done by a conservative force in changing an object's position is path independent.

First, we introduce the Lemma 2-2, which is a corollary of and a special case of Helmholtz's theorem.

be an open subset, with a Lamellar vector field F and a piecewise smooth loop c0: [0, 1] → U.

In Lemma 2-2, the existence of H satisfying [SC0] to [SC3] is crucial;the question is whether such a homotopy can be taken for arbitrary loops.

M is called simply connected if and only if for any continuous loop, c: [0, 1] → M there exists a continuous tubular homotopy H: [0, 1] × [0, 1] → M from c to a fixed point p ∈ c; that is, The claim that "for a conservative force, the work done in changing an object's position is path independent" might seem to follow immediately if the M is simply connected.

Fortunately, the gap in regularity is resolved by the Whitney's approximation theorem.

[6]: 136, 421 [12] In other words, the possibility of finding a continuous homotopy, but not being able to integrate over it, is actually eliminated with the benefit of higher mathematics.

be open and simply connected with an irrotational vector field F. For all piecewise smooth loops c: [0, 1] → U

For Faraday's law, Stokes theorem is applied to the electric field,

For Ampère's law, Stokes' theorem is applied to the magnetic field,