Euclidean distance

These names come from the ancient Greek mathematicians Euclid and Pythagoras.

In the Greek deductive geometry exemplified by Euclid's Elements, distances were not represented as numbers but line segments of the same length, which were considered "equal".

The notion of distance is inherent in the compass tool used to draw a circle, whose points all have the same distance from a common center point.

The connection from the Pythagorean theorem to distance calculation was not made until the 18th century.

A more complicated formula, giving the same value, but generalizing more readily to higher dimensions, is:[1]

In this formula, squaring and then taking the square root leaves any positive number unchanged, but replaces any negative number by its absolute value.

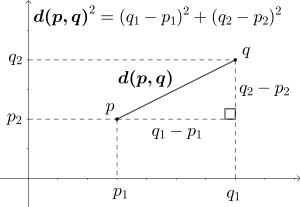

This can be seen by applying the Pythagorean theorem to a right triangle with horizontal and vertical sides, having the line segment from

[3] It is also possible to compute the distance for points given by polar coordinates.

In three dimensions, for points given by their Cartesian coordinates, the distance is

For points in the plane, this can be rephrased as stating that for every quadrilateral, the products of opposite sides of the quadrilateral sum to at least as large a number as the product of its diagonals.

However, Ptolemy's inequality applies more generally to points in Euclidean spaces of any dimension, no matter how they are arranged.

[13] According to the Beckman–Quarles theorem, any transformation of the Euclidean plane or of a higher-dimensional Euclidean space that preserves unit distances must be an isometry, preserving all distances.

[14] In many applications, and in particular when comparing distances, it may be more convenient to omit the final square root in the calculation of Euclidean distances, as the square root does not change the order (

[15] For instance, the Euclidean minimum spanning tree can be determined using only the ordering between distances, and not their numeric values.

Comparing squared distances produces the same result but avoids an unnecessary square-root calculation and sidesteps issues of numerical precision.

Beyond its application to distance comparison, squared Euclidean distance is of central importance in statistics, where it is used in the method of least squares, a standard method of fitting statistical estimates to data by minimizing the average of the squared distances between observed and estimated values,[17] and as the simplest form of divergence to compare probability distributions.

[18] The addition of squared distances to each other, as is done in least squares fitting, corresponds to an operation on (unsquared) distances called Pythagorean addition.

[15] Squared Euclidean distance does not form a metric space, as it does not satisfy the triangle inequality.

The squared distance is thus preferred in optimization theory, since it allows convex analysis to be used.

Since squaring is a monotonic function of non-negative values, minimizing squared distance is equivalent to minimizing the Euclidean distance, so the optimization problem is equivalent in terms of either, but easier to solve using squared distance.

[22] In more advanced areas of mathematics, when viewing Euclidean space as a vector space, its distance is associated with a norm called the Euclidean norm, defined as the distance of each vector from the origin.

[24] It can be extended to infinite-dimensional vector spaces as the L2 norm or L2 distance.

[26] Other common distances in real coordinate spaces and function spaces:[27] For points on surfaces in three dimensions, the Euclidean distance should be distinguished from the geodesic distance, the length of a shortest curve that belongs to the surface.

Both concepts are named after ancient Greek mathematician Euclid, whose Elements became a standard textbook in geometry for many centuries.

[29] Concepts of length and distance are widespread across cultures, can be dated to the earliest surviving "protoliterate" bureaucratic documents from Sumer in the fourth millennium BC (far before Euclid),[30] and have been hypothesized to develop in children earlier than the related concepts of speed and time.

[31] But the notion of a distance, as a number defined from two points, does not actually appear in Euclid's Elements.

Instead, Euclid approaches this concept implicitly, through the congruence of line segments, through the comparison of lengths of line segments, and through the concept of proportionality.

[32] The Pythagorean theorem is also ancient, but it could only take its central role in the measurement of distances after the invention of Cartesian coordinates by René Descartes in 1637.

The distance formula itself was first published in 1731 by Alexis Clairaut.

[34] Although accurate measurements of long distances on the Earth's surface, which are not Euclidean, had again been studied in many cultures since ancient times (see history of geodesy), the idea that Euclidean distance might not be the only way of measuring distances between points in mathematical spaces came even later, with the 19th-century formulation of non-Euclidean geometry.