Scleractinia

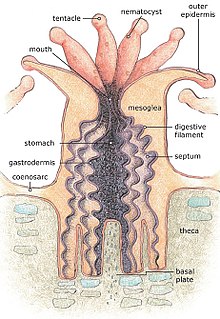

The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mouth is fringed with tentacles.

These polyps reproduce asexually by budding, but remain attached to each other, forming a multi-polyp colony of clones with a common skeleton, which may be up to several metres in diameter or height according to species.

The shape and appearance of each coral colony depends not only on the species, but also on its location, depth, the amount of water movement and other factors.

In modern times stony corals numbers are expected to decline due to the effects of global warming and ocean acidification.

The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc surrounded by a ring of tentacles.

Unlike other cnidarians however, the cavity is subdivided by a number of radiating partitions, thin sheets of living tissue, known as mesenteries.

[5] The polyps are connected by horizontal sheets of tissue known as coenosarc extending over the outer surface of the skeleton and completely covering it.

These sheets are continuous with the body wall of the polyps, and include extensions of the gastrovascular cavity, so that food and water can circulate between all the different members of the colony.

By contrast, in some fossil corals, adjacent septa lie in order of increasing age, a pattern termed serial and produces a bilateral symmetry.

In the case of bushy corals such as Acropora, lateral budding from axial polyps form the basis of the trunk and branches.

[10] Scleractinians fall into one of two main categories: In reef-forming corals, the endodermal cells are usually replete with symbiotic unicellular dinoflagellates known as zooxanthellae.

The oxygen byproduct of photosynthesis and the additional energy derived from sugars produced by zooxanthellae enable these corals to grow at a rate up to three times faster than similar species without symbionts.

These corals typically grow in shallow, well-lit, warm water with moderate to brisk turbulence and abundant oxygen, and prefer firm, non-muddy surfaces on which to settle.

In addition to capturing prey in this way, many stony corals also produce mucus films they can move over their bodies using cilia; these trap small organic particles which are then pulled towards and into the mouth.

They thrive at much colder temperatures and can live in total darkness, deriving their energy from the capture of plankton and suspended organic particles.

Pieces of branching corals may get detached during storms, by strong water movement or by mechanical means, and fragments fall to the sea bed.

[15] In other species, small balls of tissue detach themselves from the coenosarc, differentiate into polyps and start secreting calcium carbonate to form new colonies, and in Pocillopora damicornis, unfertilised eggs can develop into viable larvae.

[16] In temperate regions, the usual pattern is synchronized release of eggs and sperm into the water during brief spawning events, often related to the phases of the moon.

[16] There is little evidence on which to base a hypothesis about the origin of the scleractinians; plenty is known about modern species but very little about fossil specimens, which first appeared in the record in the Middle Triassic (240 million years ago).

Scleractinian corals were probably at their greatest diversity in the Jurassic and all but disappeared in the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous, about 18 out of 67 genera surviving.

The phenomenon seems to have evolved independently on numerous occasions during the Tertiary, and the genera Astrangia, Madracis, Cladocora and Oculina, all in different families, each have both zooxanthellate and non-zooxanthellate members.

[22] Endosymbionts, on the other hand, which rely on specialized conditions and access to light to survive, are especially vulnerable to prolonged darkness, temperature change, and eutrophication, all of which have been hallmarks of past mass extinctions.

Therefore, it is possible that coral and zooxanthellate coevolved loosely, with the relationship dissolving when advantages decreased, then reforming when conditions stabilized.

[27] The 1952 classification by French zoologist J. Alloiteau was built on these earlier systems but included more microstructural observations and did not involve the anatomical characters of the polyp.

Bryan and D. Hill stressed the importance of microstructural observations by proposing that stony corals begin skeletal growth by configuring calcification centers, which are genetically derived.

[27] Alloiteau later showed that established morphological classifications were unbalanced and that there were many examples of convergent evolution between fossils and recent taxa.

[26] The rise of molecular techniques at the end of the 20th century prompted new evolutionary hypotheses that were different from ones founded on skeletal data.

[27] The 1996 analysis of mitochondrial RNA undertaken by American zoologists Sandra Romano and Stephen Palumbi found that molecular data supported the assembling of species into the existing families, but not into the traditional suborders.

[26] The Australian zoologist John Veron and his co-workers analyzed ribosomal RNA in 1996 to obtain similar results to Romano and Palumbi, again concluding that the traditional families were plausible but that the suborders were incorrect.

They also established that stony corals are monophyletic, including all the descendants of a common ancestor, but that they are divided into two groups, the robust and complex clades.