Street hierarchy

The street hierarchy is an urban planning technique for laying out road networks that exclude automobile through-traffic from developed areas.

In places where grid networks were laid out in the pre-automotive 19th century, such as in the American Midwest, larger subdivisions have adopted a partial hierarchy, with two to five entrances off one or two main roads (arterials) thus limiting the links between them and, consequently, traffic through the neighbourhood.

In the pre-automotive era of cities, traces of the concept of a hierarchy of streets in a network appear in Greek and subsequent Roman town plans.

A clearer record of a stricter hierarchical order of streets appears in surviving and functioning Arabic-Islamic cities that originate in the late first millennium AD such as the Medina of Tunis, Marrakesh, Fez, and Damascus.

These arterials were decreed to be at least wide enough for two crossing loaded animals, 3.23 to 3.5 m.[2] This tendency for hierarchical organization of streets was so pervasive in the Arab-Islamic tradition that even cities that were laid out on a uniform grid by Greeks or Romans, were transformed by their subsequent Islamic conquerors and residents, as in the case of Damascus.

In the 1960s, when operations research and rational planning were the prevailing analytical tools, street hierarchy was seen as a major improvement over the regular, undifferentiated, "messy" grid system.

Use of the street hierarchy is a nearly universal characteristic of the "edge city", a roughly post-1970 form of urban development exemplified by places such as Tysons Corner, Virginia, and Schaumburg, Illinois.

In areas with low developer impact fees, cities often fail to provide adequate maintenance of internal and arterial roads serving newly constructed subdivisions.

New Urbanists decry the street hierarchy's deleterious effects on pedestrian travel, which is made easy and pleasant within the subdivision but is virtually impossible outside it.

Residential subdivisions usually have no pedestrian connections between themselves and adjacent commercial areas, and are often separated from them by high masonry walls intended to block noise.

New Urbanist writers like Andres Duany and James Howard Kunstler often point out the absurd nature of car trips forced by the street hierarchy: while a grocery store may be less than a quarter-mile distant physically from a given home in a subdivision, the barriers to pedestrian travel presented by the street hierarchy mean that getting a gallon of milk requires a car trip of a mile or more in each direction.

Jane Jacobs, among other commentators, has gone so far as to say that modern suburban design—of which the street hierarchy is the key component—is a major factor in the sedentary lifestyle of today's children.

[5] Mass transit advocates contend that the street hierarchy's denigration of pedestrian traffic also reduces the viability of public transportation in areas where it prevails, sharply curtailing the mobility of those who do not own cars or cannot drive them, such as disabled persons, teenagers, and the elderly.

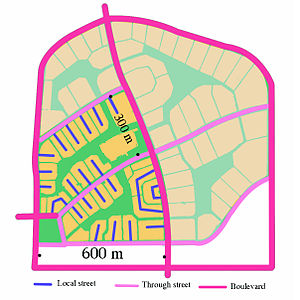

A common practice in conventional subdivision design is a road pattern that limits access to the arterials (or boulevards) to few points of entry and exit.

The study concluded that the non-hierarchical, traditional layout generally shows lower peak speed and shorter, more frequent intersection delays than the hierarchical pattern.

The study concluded that all types of layouts perform adequately in most low to moderate population density scenarios up to a certain threshold of 62 persons per hectare (ppha).

This confirms the density influence on congestion levels and that a hierarchical pattern can improve flow if laid out following the access restrictions proposed in the ITE/CNU practice guide.

In edge cities the number of cars exiting a large subdivision to an arterial that links to a highway can be extremely high, leading to miles-long queues to get on freeway ramps nearby.

Recent studies have found higher traffic fatality rates in outlying suburban areas than in central cities and inner suburbs with smaller blocks and more-connected street patterns.

An earlier study[13] found significant differences in recorded accidents between residential neighbourhoods that were laid out on an undifferentiated grid and those that included culs-de-sac and crescents in a hierarchical structure.

[17][18][19] While street hierarchies remain the default mode of suburban design in the United States, its 21st century usefulness depends on the prevalence of low density developments.

Grids were used in New Orleans to fit a population that had at one time reached over 700,000 into 180 square miles (470 km2) of land with over 20 percent of that number being dedicated to uninhabitable wetlands.

The "smart growth" movement calls for street patterns with a high degree of connectivity, and with it a more balanced provision for various travel modes, both vehicular and non-vehicular.