Sugar refinery

Approaching the end of the 16th century, the art of refining sugar had spread to Germany, Fifty years later, the Dutch started their refineries, which soon dominated the European market.

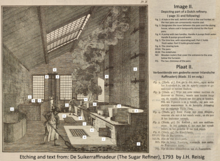

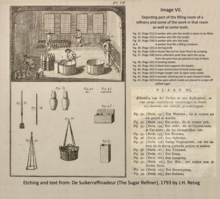

In the early modern era (AD 1500 to 1800) the sugar refinery process consisted of some standard steps.

The albumen of the blood then coagulated and entangled the mechanical impurities of the sugar, forming a scum that was constantly removed.

For this, the syrup was transferred to a vessel called a cooler, where it was agitated with wooden oars till it granulated.

They did not necessarily have to be in a port city, because at the time goods were generally transloaded from a ship onto a barge before reaching their destination.

Sugar refineries are often located in heavy sugar-consuming regions such as North America, Europe, and Japan.

Since the 1990s, many state-of-the art sugar refineries have been built in the Middle East and North Africa region, e.g. in Dubai, Saudi Arabia and Algeria.

[4] From about 1800 the Industrial Revolution changed the refining process by introducing steam power and all kinds of machinery.

The pre-1800 refinery was extensively described in the Netherlands, because the Dutch Republic dominated the trade in and refining of sugar for a long time.

[5] Ideally, the warehouse and the refinery were separate buildings, but with the high real estate prices in Holland, this was rare.

[10] Below the refinery was a lead tube that allowed to pump fresh water that, in Amsterdam, was brought by barge schuitwater to the rear of the building.

During heating the lime bound to impurities and formed a solidified scum, which was removed with a skimmer,[18] resembling a perforated spade, with a 6–8 feet long handle.

[21] Small portions of the clarified juice were fed to the first pan, which was brought to boil by a brisk fire.

The first option to continue refining was to drain off the remaining water by using gravity, which would result in loaf, lump or bastard sugar.

Ideally, the next batch of boiled sugar was done at this exact moment and was then added to the cooling pan.

They were then stacked up to each other while the outer rows were supported by prefixes voorzetsels, i.e. broken molds that were not fit for any other purpose.

[38] Glasgow was an important center for the production of the very heavy machinery required for cane sugar mills.

[39] This probably contributed to the growth of Greenock as a center for sugar refining, which required lighter, but comparable machinery.

Eventually the concentration of raw sugar factories meant that (central) refineries became superfluous.

These could process 14,000,000 pounds of raw sugar[50] The refinery of Canby & Lovering used steam power and vacuum pans, but was about to be joined by another.

[52] The refinery of Teaman, Tobias & Co. on Liberty street was a wealthy company established in the building known as The Old Sugar House.

This film of molasses offers an incubator for microbial growth, leading to quality loss related to storage.

All clarification treatments include mixing the melted liquor with hot milk of lime (a suspension of calcium hydroxide in water).

[63] This treatment precipitates a number of impurities, including multivalent anions such as sulfate, phosphate, citrate and oxalate, which precipitate as their calcium salts and large organic molecules such as proteins, saponins and pectins, which aggregate in the presence of multivalent cations.

[68] The result is "thick juice", roughly 60% sucrose by weight and similar in appearance to maple syrup.

Thick juice can be stored in tanks for later processing, spreading the load on later steps of the crystallization plant.

Thick juice is mixed with low grade crystal sugar recycled from other parts of the process in a melter and filtered giving "standard liquor".

The crystallization phase starts by feeding the standard liquor to the vacuum pans, typically at 76 Brix.

The resulting sugar crystal and syrup mix is called a massecuite, from "cooked mass" in French.

Many road authorities in North America use desugared beet molasses as de-icing or anti-icing products in winter control operations.