Supernova nucleosynthesis

A rapid final explosive burning[1] is caused by the sudden temperature spike owing to passage of the radially moving shock wave that was launched by the gravitational collapse of the core.

[4][5] As a result of the ejection of the newly synthesized isotopes of the chemical elements by supernova explosions, their abundances steadily increased within interstellar gas.

Elements heavier than nickel are comparatively rare owing to the decline with atomic weight of their nuclear binding energies per nucleon, but they too are created in part within supernovae.

Of greatest interest historically has been their synthesis by rapid capture of neutrons during the r-process, reflecting the common belief that supernova cores are likely to provide the necessary conditions.

In 1946, Fred Hoyle proposed that elements heavier than hydrogen and helium would be produced by nucleosynthesis in the cores of massive stars.

At this time, the nature of supernovae was unclear and Hoyle suggested that these heavy elements were distributed into space by rotational instability.

[6] Hoyle also predicted that the collapse of the evolved cores of massive stars was "inevitable" owing to their increasing rate of energy loss by neutrinos and that the resulting explosions would produce further nucleosynthesis of heavy elements and eject them into space.

[10] During his 1955 discussions in Cambridge with his co-authors in preparation of the B²FH first draft in 1956 in Pasadena,[11] Hoyle's modesty had inhibited him from emphasizing to them the great achievements of his 1954 theory.

White dwarfs were proposed as possible progenitors of certain supernovae in the late 1960s,[12] although a good understanding of the mechanism and nucleosynthesis involved did not develop until the 1980s.

Brilliant as these founding papers were, a cultural disconnect soon emerged with a younger generation of scientists who began to construct computer programs[15] that would eventually yield numerical answers for the advanced evolution of stars[16] and the nucleosynthesis within them.

Without exothermic energy from fusion, the core of the pre-supernova massive star loses heat needed for pressure support, and collapses owing to the strong gravitational pull.

As the star collapses, this mantle collides violently with the growing incompressible stellar core, which has a density almost as great as an atomic nucleus, producing a shockwave that rebounds outward through the unfused material of the outer shell.

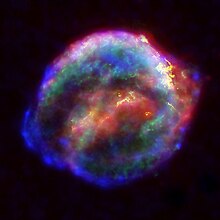

[2][22] The energy deposited by the shockwave somehow leads to the star's explosion, dispersing fusing matter in the mantle above the core into interstellar space.

At these temperatures, silicon and other isotopes suffer photoejection of nucleons by energetic thermal photons (γ) ejecting especially alpha particles (4He).

[23] The nuclear process of silicon burning differs from earlier fusion stages of nucleosynthesis in that it entails a balance between alpha-particle captures and their inverse photo ejection which establishes abundances of all alpha-particle elements in the following sequence in which each alpha particle capture shown is opposed by its inverse reaction, namely, photo ejection of an alpha particle by the abundant thermal photons: The alpha-particle nuclei 44Ti and those more massive in the final five reactions listed are all radioactive, but they decay after their ejection in supernova explosions into abundant isotopes of Ca, Ti, Cr, Fe and Ni.

However 60Zn has slightly more mass per nucleon than 56Ni, and thus would require a thermodynamic energy loss rather than a gain as happened in all prior stages of nuclear burning.

However, since no additional heat energy can be generated via new fusion reactions, the final unopposed contraction rapidly accelerates into a collapse lasting only a few seconds.

The escaping portion of the supernova core may initially contain a large density of free neutrons, which may synthesize, in about one second while inside the star, roughly half of the elements in the universe that are heavier than iron via a rapid neutron-capture mechanism known as the r-process.

Stars with initial masses less than about eight times the sun never develop a core large enough to collapse and they eventually lose their atmospheres to become white dwarfs, stable cooling spheres of carbon supported by the pressure of degenerate electrons.

This limits their modest yields returned to interstellar gas to carbon-13 and nitrogen-14, and to isotopes heavier than iron by slow capture of neutrons (the s-process).

The result is a white dwarf which exceeds its Chandrasekhar limit and explodes as a type Ia supernova, synthesizing about a solar mass of radioactive 56Ni isotopes, together with smaller amounts of other iron peak elements.

The yield that is ejected is substantially fused in last-second explosive burning caused by the shock wave launched by core collapse.

Modern thinking is that the r-process yield may be ejected from some supernovae but swallowed up in others as part of the residual neutron star or black hole.

When released from the huge internal pressure of the neutron star, this neutron-rich spherical ejecta[37][38] expands and radiates detected optical light for about a week.