Susan La Flesche Picotte

Susan La Flesche Picotte (June 17, 1865 – September 18, 1915)[1] was a Native American medical doctor and reformer and member of the Omaha tribe.

She also worked to help other Omaha navigate the bureaucracy of the Office of Indian Affairs and receive the money owed to them for the sale of their land.

In 1853, he was adopted by Chief Big Elk, who chose him as his successor, and La Flesche became the principal leader of the Omaha tribe around 1855.

[8] Her older half-brother Francis La Flesche, born in 1857 to her father's second wife, later became a renowned ethnologist, anthropologist and musicologist (or ethnomusicologist), who specialized in the study of the Omaha and Osage cultures.

As she grew, La Flesche learned the traditions of her heritage, but her parents felt certain rituals would be detrimental in the white world.

[10] As a child, La Flesche witnessed a sick Indian woman die after a white doctor refused to treat her.

[16] While La Flesche was a student at the Hampton Institute, she became romantically involved with a young Sioux man named Thomas Ikinicapi.

[20] La Flesche asked for financial assistance from family friend Alice Fletcher, an ethnographer from Massachusetts who had a broad network of contacts within women's reform organizations.

[25][11] The Association requested that she remain single during her time at medical school and for several years after her graduation in order to focus on her practice.

[17] At the WMCP, La Flesche studied chemistry, anatomy, physiology, histology, pharmaceutical science, obstetrics, and general medicine, and, like her peers, did clinical work at facilities in Philadelphia alongside students from other colleges, both male and female.

[26] While attending medical school, La Flesche began to dress like her white classmates and wore her hair in a bun as they did.

[18] After La Flesche's second year in medical school, she returned home to help her family, many of whom had fallen ill due to a measles outbreak.

[33] From her office in a corner of the schoolyard, with the supplies provided by the Connecticut Indian Association, she helped people with their health but also with more mundane tasks, such as writing letters and translating official documents.

[34] La Flesche was widely trusted in the community, making house calls and caring for patients sick with tuberculosis, influenza, cholera, dysentery, and trachoma.

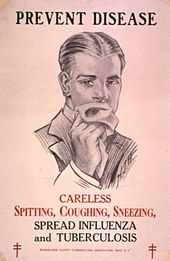

[40] In addition to caring for the Omaha people's immediate medical problems, Picotte sought to educate her community about preventive medicine and other public health issues, including temperance.

[42] La Flesche supported measures such as coercion and punishment to dissuade individuals from alcohol consumption within the Omaha community.

Under her father's rule, a secret police system was instilled which supported corporal punishment to discipline those who consumed alcohol.

[40] Later, she lobbied for the Meilklejohn Bill, which would outlaw the sale of alcohol to any recipient of allotted land whose property was still held in trust by the government.

[46] Beyond temperance, Picotte worked on public health issues in the wider community, including school hygiene, food sanitation, and efforts to combat the spread of tuberculosis.

[55] At the time of Henry's death, the land was still held in trust by the government, and in order to receive the monies from its sale, his heirs had to prove competency.

In her position as a doctor, Picotte had gained the trust of her community, and her role as a local leader had expanded from letter writer/interpreter to defender of Omaha land interests.

[61] In a bizarre twist, Picotte, who had spent much of her life proclaiming that the Omaha had the same capacity for "civilization" as any white man, wrote to the Indian Office in 1909 to say that some of her people were too incompetent to protect themselves against the fraudsters and thus needed the continued guardianship of the federal government.

[63] Picotte had been part of a movement among the Omaha opposing this consolidation, and used letters and harshly critical newspaper articles to get her point across to the OIA bureaucracy.

[64] She argued that the unnecessary red tape created by the consolidation was nothing but an extra burden on the Omaha and was further proof that the OIA treated them like children, rather than as citizens ready to participate in a democracy.

[65] She continued to work on her community's behalf until the end of her life, though much of that seemed to be in vain, as her people lost many of their ancestral lands and became more, not less, dependent on the OIA.

In medical school, she had been bothered by trouble breathing, and after a few years working on the reservation, she was forced to take a break to recover her health in 1892, as she suffered from chronic pain in her neck, head, and ears.

Caryl Picotte made a career in the United States Army and served in World War II, eventually settling in El Cajon, California.

[77] On October 11, 2021, Nebraska's first officially recognized Indigenous Peoples' Day, a bronze sculpture of Picotte by Benjamin Victor was unveiled by her descendants on Lincoln's Centennial Mall.

Judi gaiashkibos (national leader on Native American issues) was instrumental in elevating Picotte's legacy and the creation of the sculpture.