Sustainable energy

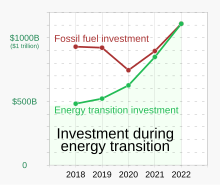

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that 2.5% of world gross domestic product (GDP) would need to be invested in the energy system each year between 2016 and 2035 to limit global warming to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F).

Finally, governments can encourage clean energy deployment with policies such as carbon pricing, renewable portfolio standards, and phase-outs of fossil fuel subsidies.

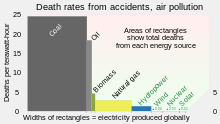

[6][7] The current energy system contributes to many environmental problems, including climate change, air pollution, biodiversity loss, the release of toxins into the environment, and water scarcity.

[14][15] The 2015 international Paris Agreement on climate change aims to limit global warming to well below 2 °C (3.6 °F) and preferably to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F); achieving this goal will require that emissions be reduced as soon as possible and reach net-zero by mid-century.

[16] The burning of fossil fuels and biomass is a major source of air pollution,[17][18] which causes an estimated 7 million deaths each year, with the greatest attributable disease burden seen in low and middle-income countries.

[19] Fossil-fuel burning in power plants, vehicles, and factories is the main source of emissions that combine with oxygen in the atmosphere to cause acid rain.

[27] Meeting existing and future energy demands in a sustainable way is a critical challenge for the global goal of limiting climate change while maintaining economic growth and enabling living standards to rise.

Behavioural changes such as using videoconferencing rather than business flights, or making urban trips by cycling, walking or public transport rather than by car, are another way to conserve energy.

[40] Government policies to improve efficiency can include building codes, performance standards, carbon pricing, and the development of energy-efficient infrastructure to encourage changes in transport modes.

[44] For example, recent technical efficiency improvements in transport and buildings have been largely offset by trends in consumer behaviour, such as selecting larger vehicles and homes.

[49] Renewable energy projects sometimes raise significant sustainability concerns, such as risks to biodiversity when areas of high ecological value are converted to bioenergy production or wind or solar farms.

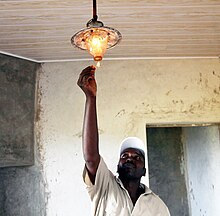

[52][53] For more than half of the 770 million people who currently lack access to electricity, decentralised renewable energy such as solar-powered mini-grids is likely the cheapest method of providing it by 2030.

[84] Geothermal energy carries a risk of inducing earthquakes, needs effective protection to avoid water pollution, and releases toxic emissions which can be captured.

In some cases, the impacts of land-use change, cultivation, and processing can result in higher overall carbon emissions for bioenergy compared to using fossil fuels.

[105] Second-generation biofuels which are produced from non-food plants or waste reduce competition with food production, but may have other negative effects including trade-offs with conservation areas and local air pollution.

[132] Although fusion power has taken steps forward in the lab, the multi-decade timescale needed to bring it to commercialization and then scale means it will not contribute to a 2050 net zero goal for climate change mitigation.

[135] Many climate change mitigation pathways envision three main aspects of a low-carbon energy system: Some energy-intensive technologies and processes are difficult to electrify, including aviation, shipping, and steelmaking.

[143][144] With good planning and management, pathways exist to provide universal access to electricity and clean cooking by 2030 in ways that are consistent with climate goals.

[145] However, there remains a window of opportunity for many poor countries and regions to "leapfrog" fossil fuel dependency by developing their energy systems based on renewables, given adequate international investment and knowledge transfer.

[160] One of the easiest and fastest ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is to phase out coal-fired power plants and increase renewable electricity generation.

[136] Climate change mitigation pathways envision extensive electrification—the use of electricity as a substitute for the direct burning of fossil fuels for heating buildings and for transport.

Off-grid and mini-grid systems based on renewable energy, such as small solar PV installations that generate and store enough electricity for a village, are important solutions.

[164] Recycling can meet some of this demand if product lifecycles are well-designed, however achieving net zero emissions would still require major increases in mining for 17 types of metals and minerals.

[186][187] The energy efficiency of cars has increased over time,[188] but shifting to electric vehicles is an important further step towards decarbonising transport and reducing air pollution.

[212] The universal adoption of clean cooking facilities, which are already ubiquitous in rich countries,[210] would dramatically improve health and have minimal negative effects on climate.

[225][226] Governments can accelerate energy system transformation by leading the development of infrastructure such as long-distance electrical transmission lines, smart grids, and hydrogen pipelines.

[222] Government-funded research, procurement, and incentive policies have historically been critical to the development and maturation of clean energy technologies, such as solar and lithium batteries.

[228] In the IEA's scenario for a net zero-emission energy system by 2050, public funding is rapidly mobilised to bring a range of newer technologies to the demonstration phase and to encourage deployment.

[237] These place tariffs on imports from countries with less stringent climate policies, to ensure that industries subject to internal carbon prices remain competitive.

[240][241] In addition to domestic policies, greater international cooperation is required to accelerate innovation and to assist poorer countries in establishing a sustainable path to full energy access.