Swing Around the Circle

Swing Around the Circle is the nickname for a speaking campaign undertaken by U.S. President Andrew Johnson between August 27 and September 15, 1866, in which he tried to gain support for his obstructionist Reconstruction policies and for his preferred candidates (mostly Democrats) in the forthcoming midterm Congressional elections.

The tour's nickname came from the route that the campaign took: "Washington, D.C., to New York, west to Chicago, south to St. Louis, and east through the Ohio River valley back to the nation's capital".

However, as Congress began enacting legislation to guarantee the rights of former slaves, former slaveowner Johnson refocused on actions (including vetoes of civil rights legislation and mass pardoning of former Confederate officials) that resulted in severe oppression of freed slaves in the Southern states, as well as the return of high-ranking Confederate officials and pre-war aristocrats to power in state and federal government.

In addition, to increase both his audience and his prestige, Johnson brought along heroes of the Civil War such as David Farragut, George Custer, and Ulysses S. Grant (by then the most admired living man in the country) to stand next to him while he spoke.

[5]Another problem was that semi-literate Johnson never prepared much for speeches; he was a free-wheeling stump speaker who put on a show for the audience on hand using a chain of grievances as the framework for his performance.

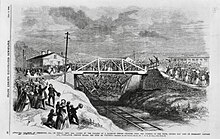

[6] In the 18 days of the tour, Johnson and his entourage made stops in Baltimore, Maryland; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; New York City, West Point, Albany, Auburn, Niagara Falls, and Buffalo, New York; Cleveland and Toledo, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Chicago, Springfield, and Alton, Illinois; St. Louis, Missouri; Indianapolis, Indiana; Louisville, Kentucky; Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio; and Pittsburgh and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, as well as short stops in smaller towns between.

According to Johnson biographer Hans Trefousse, at each stop on the tour he had delivered [...] substantially the same speech, in which he thanked his audience for its welcome, paid homage to the army and navy, and declared that the humble individual standing before them had not changed.

[7]The press nonetheless gave him overwhelmingly positive coverage throughout the first leg of the tour (although the circumstances made his customary introduction—"Fellow citizens, it is not for the purpose of making speeches that I now appear before you"—a particular laugh line).

[8] For example, according to the writer from the Missouri Democrat in the September 10 issue: [Johnson's tone of voice was] sneering, sarcastic, and malignant whenever he referred to the Freedmen's Bureau, to Congress ... or to impartial suffrage; defiant and revolutionary when he talked of the vote; boastful and triumphant when he spoke of having "turned loose" over 40,000 of captured rebels; intensely and over poweringly egotistic at all times.

His favorite beginning for a sentence was "Yes," sounded like something about half way between "Yeas," and "yahs," in a drawling manner and loud, harsh tone, and no words can express the sheer, dogmatic, and insufferably self-satisfied meaning which he threw into it.

Because the audience was as large as it had been at previous stops, nothing seemed out of the ordinary; however, the crowd included mobs of hecklers, many of them plants by the Radical Republicans, who goaded Johnson into engaging them in mid-speech; when one of them yelled "Hang Jeff Davis!"

The give-and-take discussion he envisioned before leaving the White House proved impossible when on warm September evenings huge crowds gathered under hotel balconies under conditions of high tension and excitement.

The president was also the target of the two most important satirical journalists of the era—humorist David Ross Locke (writing in his persona as the backward southerner Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby) and cartoonist Thomas Nast, who created three large illustrations lampooning Johnson and the Swing that became legendary.

Thaddeus Stevens gave a speech referring to the Swing as "the remarkable circus that traveled through the country" that "cut outside the circle and entered into street brawls with common blackguards."

Charles Sumner, meanwhile, gave a stump speech of his own, encouraging his audiences to vote for Republicans in the fall elections because "the President must be taught that usurpation and apostasy cannot prevail."

Because Johnson had been drunk at his own vice-presidential inauguration the year before, reporters and political opponents took his inebriation as fact and declared him a "vulgar, drunken demagogue who was disgracing the presidency.

The Swing Around the Circle's impact was apparent even in the articles of impeachment, with the tenth of eleven articles charging that the President "did...make and declare, with a loud voice certain intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues, and therein utter loud threats and bitter menaces, as well against Congress as the laws of the United States duly enacted thereby, amid the cries, jeers and laughter of the multitudes then assembled in hearing.

Thus, in effect, the Swing Around the Circle began a long series of political defeats that crippled Johnson, the Democratic Party and the presidency for several years.