Pope Sylvester II

[6] Gerbert studied under the direction of Bishop Atto of Vich, some 60 km north of Barcelona, and probably also at the nearby Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll.

[7] Like all Catalan monasteries, it contained manuscripts from Muslim Spain and especially from Cordoba, one of the intellectual centres of Europe at that time: the library of al-Hakam II, for example, had thousands of books (from science to Greek philosophy).

[8] Borrell II was facing major defeat from the Andalusian powers so he sent a delegation to Córdoba to request a truce.

Gerbert was fascinated by the stories of the Mozarab Christian bishops and judges who dressed and talked like the Moors, well-versed in mathematics and natural sciences like the great teachers of the Islamic madrasahs.

[n 2] According to the 12th-century historian William of Malmesbury, Gerbert got the idea of the computing device of the abacus from a Moorish scholar[10] from University of Al-Qarawiyyin.

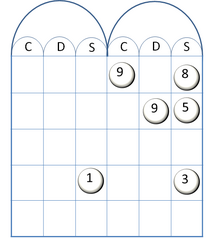

[11] The abacus that Gerbert reintroduced into Europe had its length divided into 27 parts with 9 number symbols (this would exclude zero, which was represented by an empty column) and 1,000 characters in all, crafted out of animal horn by a shieldmaker of Rheims.

[12][13][14] According to his pupil Richer, Gerbert could perform speedy calculations with his abacus that were extremely difficult for people in his day to think through using only Roman numerals.

He drew with great art and accuracy, across the colures, five other circles called parallels, which, from one pole to the other, divided the half of the sphere into thirty parts.

On the inside of this oblique circle he figured with an extraordinary art the orbits traversed by the planets, whose paths and heights he demonstrated perfectly to his pupils, as well as their respective distances.

[28] He dedicated immense sums of money to establishing the library and purchasing texts from a wide variety of western European authors.

Some years later, Otto I gave Gerbert leave to study at the cathedral school of Rheims where he was soon appointed a teacher by Archbishop Adalberon in 973.

As pope, he took energetic measures against the widespread practices of simony and concubinage among the clergy, maintaining that only capable men of spotless lives should be allowed to become bishops.

Sylvester II returned to Rome soon after the emperor's death, although the rebellious nobility remained in power, and died a little later.

Gerbert wrote a series of works dealing with matters of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music), which he taught using the basis of the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric).

In Rheims, he constructed a hydraulic-powered organ with brass pipes that excelled all previously known instruments,[31] where the air had to be pumped manually.

Besides these, as Sylvester II he wrote a dogmatic treatise, De corpore et sanguine Domini—On the Body and Blood of the Lord.

The legend of Gerbert grows from the work of the English monk William of Malmesbury in De Rebus Gestis Regum Anglorum and a polemical pamphlet, Gesta Romanae Ecclesiae contra Hildebrandum, by Cardinal Beno, a partisan of Emperor Henry IV who opposed Pope Gregory VII in the Investiture Controversy.

[citation needed] According to the legend, Gerbert, traveled to Spain in order to further his knowledge of the lawful arts, as defined by the quadrivium.

He was also reputed to have had a pact with a female demon called Meridiana, who had appeared after he had been rejected by his earthly love, and with whose help he managed to ascend to the papal throne (another legend tells that he won the papacy playing dice with the Devil).

The inscription on Gerbert's tomb reads in part Iste locus Silvestris membra sepulti venturo Domino conferet ad sonitum ("This place will yield to the sound [of the last trumpet] the limbs of buried Sylvester II, at the advent of the Lord", mis-read as "will make a sound") and has given rise to the curious legend that his bones will rattle in that tomb just before the death of a pope.

[37] The story of the crown and papal legate authority allegedly given to Stephen I of Hungary by Sylvester in the year 1000 (hence the title 'apostolic king') is noted by the 19th-century historian Lewis L. Kropf as a possible forgery of the 17th century.

[38] Likewise, the 20th-century historian Zoltan J. Kosztolnyik states that "it seems more than unlikely that Rome would have acted in fulfilling Stephen's request for a crown without the support and approval of the emperor.

But works done outside of the accepted liberal arts was condemned, including things learned from bird's songs and flight patterns, as well as the necromancy he was rumored to have taken part in.