Synapse

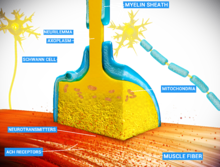

Upon release, these neurotransmitters bind to specific receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, inducing an electrical or chemical response in the target neuron.

This mechanism allows for more complex modulation of neuronal activity compared to electrical synapses, contributing significantly to the plasticity and adaptable nature of neural circuits.

In addition, a synapse serves as a junction where both the transmission and processing of information occur, making it a vital means of communication between neurons.

Both the presynaptic and postsynaptic sites contain extensive arrays of molecular machinery that link the two membranes together and carry out the signaling process.

[15][17] However, while the synaptic gap remained a theoretical construct, and was sometimes reported as a discontinuity between contiguous axonal terminations and dendrites or cell bodies, histological methods using the best light microscopes of the day could not visually resolve their separation which is now known to be about 20 nm.

It needed the electron microscope in the 1950s to show the finer structure of the synapse with its separate, parallel pre- and postsynaptic membranes and processes, and the cleft between the two.

The formation of neural circuits in nervous systems appears to heavily depend on the crucial interactions between chemical and electrical synapses.

An influx of Na+ driven by excitatory neurotransmitters opens cation channels, depolarizing the postsynaptic membrane toward the action potential threshold.

Additionally, dopamine is a neurotransmitter that exerts dual effects, displaying both excitatory and inhibitory impacts through binding to distinct receptors.

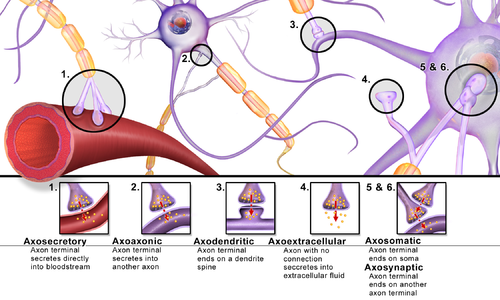

These include but are not limited to[clarification needed] axo-axonic, dendro-dendritic, axo-secretory, axo-ciliary,[28] somato-dendritic, dendro-somatic, and somato-somatic synapses.

By attaching to transmitter-gated ion channels, the neurotransmitter causes an electrical alteration in the postsynaptic cell and rapidly diffuses across the synaptic cleft.

Once released, the neurotransmitter is swiftly eliminated, either by being absorbed by the nerve terminal that produced it, taken up by nearby glial cells, or broken down by specific enzymes in the synaptic cleft.

However, they result in graded variations in membrane potential due to local permeability, influenced by the amount and duration of neurotransmitter released at the synapse.

[26] Recently, mechanical tension, a phenomenon never thought relevant to synapse function has been found to be required for those on hippocampal neurons to fire.

[27] The variations in the quantities of neurotransmitters released from the presynaptic neuron may play a role in regulating the effectiveness of synaptic transmission.

[33] Modulation of neurotransmitter release by G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is a prominent presynaptic mechanism for regulation of synaptic transmission.

The majority of medications utilized to treat schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, and sleeplessness work at chemical synapses, and many of these pharmaceuticals function by binding to transmitter-gated channels.

Memory formation involves complex interactions between neural pathways, including the strengthening and weakening of synaptic connections, which contribute to the storage of information.

Changes in postsynaptic signaling are most commonly associated with a N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR)-dependent LTP and long-term depression (LTD) due to the influx of calcium into the post-synaptic cell, which are the most analyzed forms of plasticity at excitatory synapses.

[42] Moreover, Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is best recognized for its roles in the brain, particularly in the neocortex and hippocampal regions because it serves as a ubiquitous mediator of cellular Ca2+ signals.

Synaptic disruptions can lead to a variety of negative effects, including impaired learning, memory, and cognitive function.

[45] In fact, alterations in cell-intrinsic molecular systems or modifications to environmental biochemical processes can lead to synaptic dysfunction.

The synapse is the primary unit of information transfer in the nervous system, and correct synaptic contact creation during development is essential for normal brain function.

Synaptic dysfunction, or synaptopathy, is often implicated in late-onset neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's, but the exact mechanisms contributing to this phenomenon are not fully understood.